The Esplanade’s Railway Origins

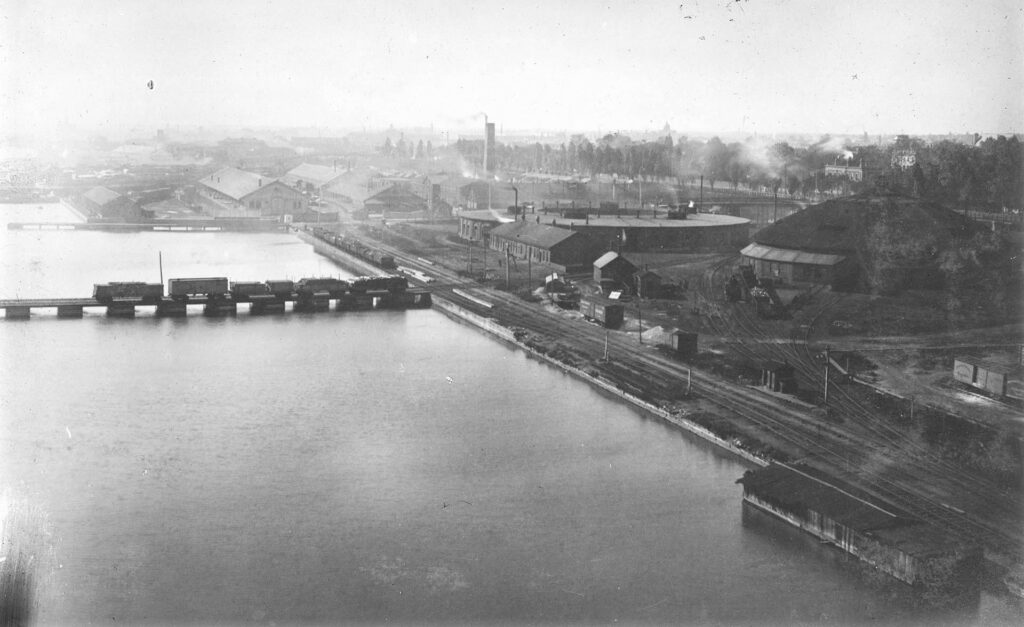

While Toronto is far from the oldest European settlement in Canada, it is no stranger to historic sites. Beyond the city’s oldest buildings, the streets themselves carry a lot of history. We’re often reminded of this each time the pavement cracks revealing the cobblestone underneath. Yonge Street, for example, is widely considered to be Toronto’s earliest street at over two centuries old. Other streets in the city, while technically considered to be newer, have their roots in the Huron, Iroquois and Mississauga communities that existed here before the 1793 founding of the Town of York by European settlers. However, there is one particular street in Toronto that has more to do with Toronto’s railway history than any other. Originally intended to beautify the waterfront, a large chunk of The Esplanade almost immediately became dedicated space for railway tracks. For 73 years from 1857 to 1930, the area presently occupied by the playground, basketball court, and greenspace of David Crombie Park carried all railway traffic east of Union Station. Even after Toronto Harbour was filled in another half kilometre south in the late 1920’s and the present rail corridor was established on an elevated embankment, railway tracks continued to occupy the Esplanade until the area’s industries departed in the latter half of the 20th Century. In this post, we will explore the story of how Toronto lost its Esplanade to the railways, and how it eventually got it back.

An Esplanade That Wasn’t Meant To Be

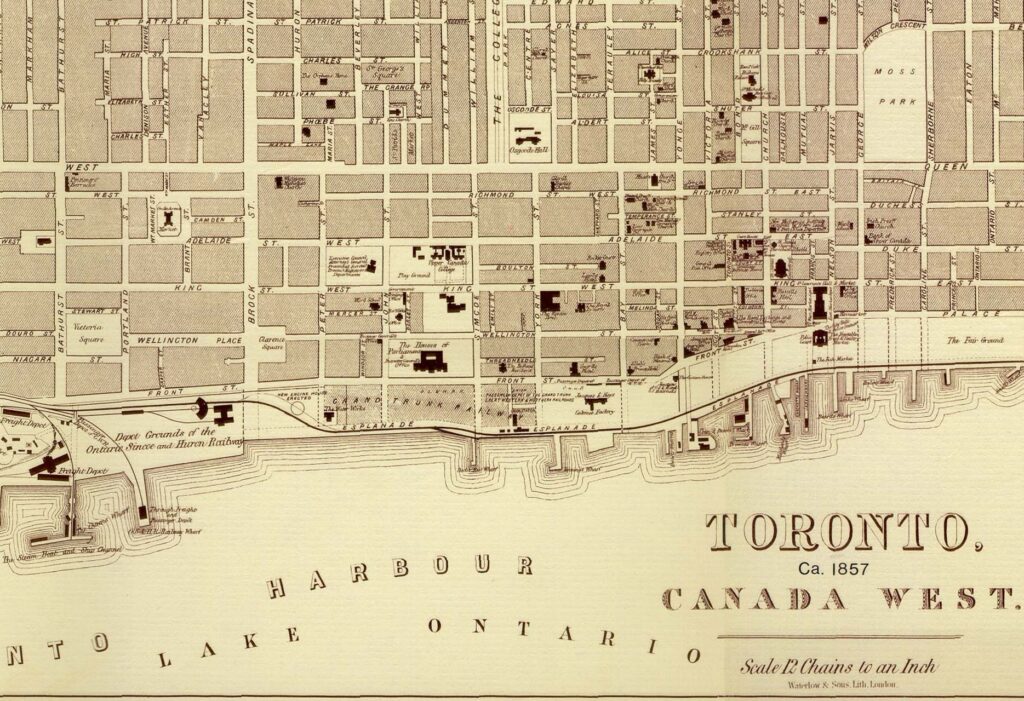

When the first railways arrived in Toronto during the 1850’s, the city’s waterfront was crowded with industrial properties which had rendered it completely impassable from a railway’s perspective. For the first railway in Toronto – the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron – this wasn’t yet a significant problem. Since the southern end of their line began within the city, their passenger station at Bay Street was satisfactory for the time being. Complications arose once the newly-formed Grand Trunk Railway set its sights on a line from Montreal to Toronto, then beyond to Stratford and Sarnia. Establishing a right-of-way along the city’s waterfront would have required a vast amount of costly expropriation, and also would have meant steep grades on both sides of the city. Avoiding these costs by staying to the north would mean cheaper construction, but threatened far fewer returns from local passenger and freight business. Luckily for the Grand Trunk, and perhaps less so for Toronto’s citizens, city officials were unintentionally in the process of paving the way for the Grand Trunk.

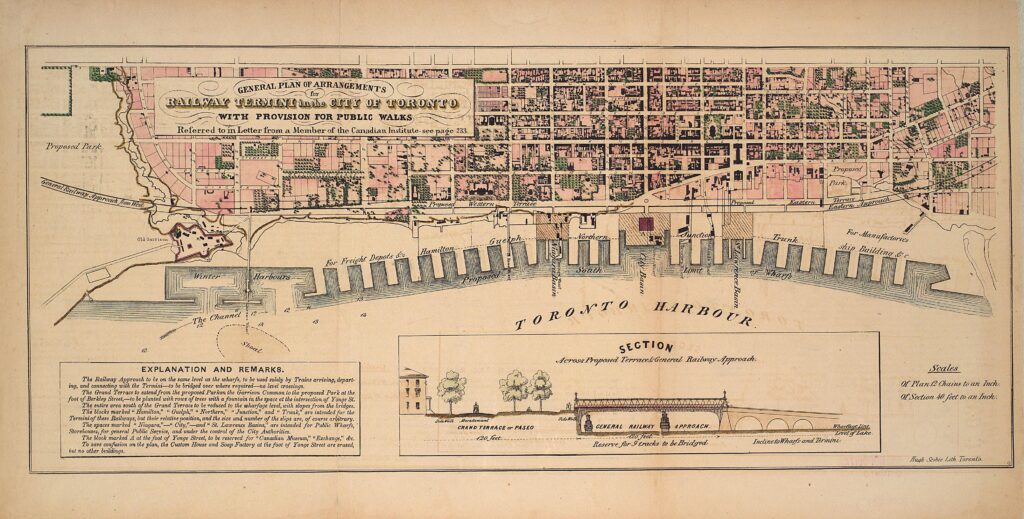

In the early 1850’s, the City of Toronto wished to beautify the waterfront and provide greater access to the shore for its residents. Many of Canada West’s leading architects submitted their designs, all of which put the focus on natural beauty and accessibility despite slight variances between them. When architect Frederick Cumberland submitted his plan for the waterfront on July 23rd, 1853, it was already known that the Grand Trunk Railway would be approaching from the east. His plan was markedly more railway-focused, and that could have been attributed to his association with the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway at the time, but it certainly did not sacrifice beauty or safety. The plan included an elevated “grand terrace” measuring 120 feet in width running east-west along the waterfront, which included a Macadam road lined with trees, sidewalks, and a fountain at the intersection with Yonge Street. Below the terrace to the south, an additional 120 feet of space – wide enough for nine tracks – was to be reserved for the Grand Trunk Railway, and presumably any other railway that wished to occupy that area. To ensure the safety of pedestrians and road traffic, a series of ten bridges were to pass over the rail corridor and connect the terrace with lake level. This idea of keeping the road and rail at separate levels was an important one, as we will soon find out, but ultimately one that would not materialize for a long time. The city chose to go with a far more basic plan, a simple Esplanade with a road measuring 100 feet in width along the entire waterfront. It was to begin at Spadina Avenue and end at Parliament Street.

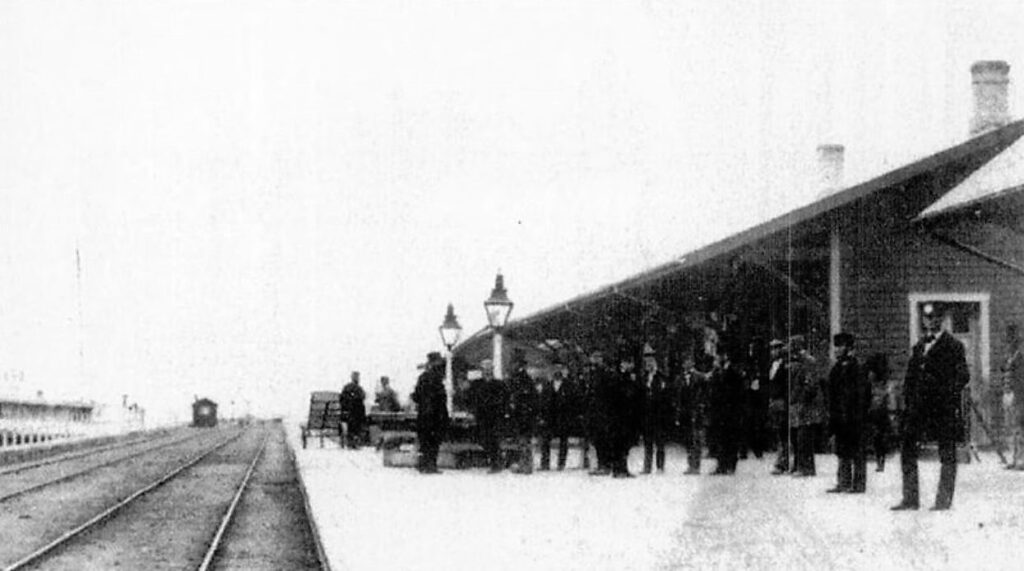

Grand Trunk officials caught wind of the Esplanade plan and strong-armed the city into allowing them access to it. On January 21st, 1856, the City of Toronto agreed to allow the Grand Trunk to occupy a 40-foot strip down the middle of the 100-foot road. In return, the Grand Trunk would underwrite the necessary filling required to build the Esplanade. The Grand Trunk paid a total of 10,000 pounds for this, worth just over $1.5 million today in Canadian dollars when adjusted for inflation. As the Esplanade’s construction progressed the Grand Trunk established temporary passenger terminals on either side of the city in 1855 and 1856. They were temporarily joined across the under-construction Esplanade in 1857, but it took until the opening of Toronto’s first Union Station on June 21st, 1858 for the permanent infrastructure to be put in place. In addition to the Grand Trunk, the first Union Station was also shared with the Great Western Railway and the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway.

A Labyrinth of Tracks

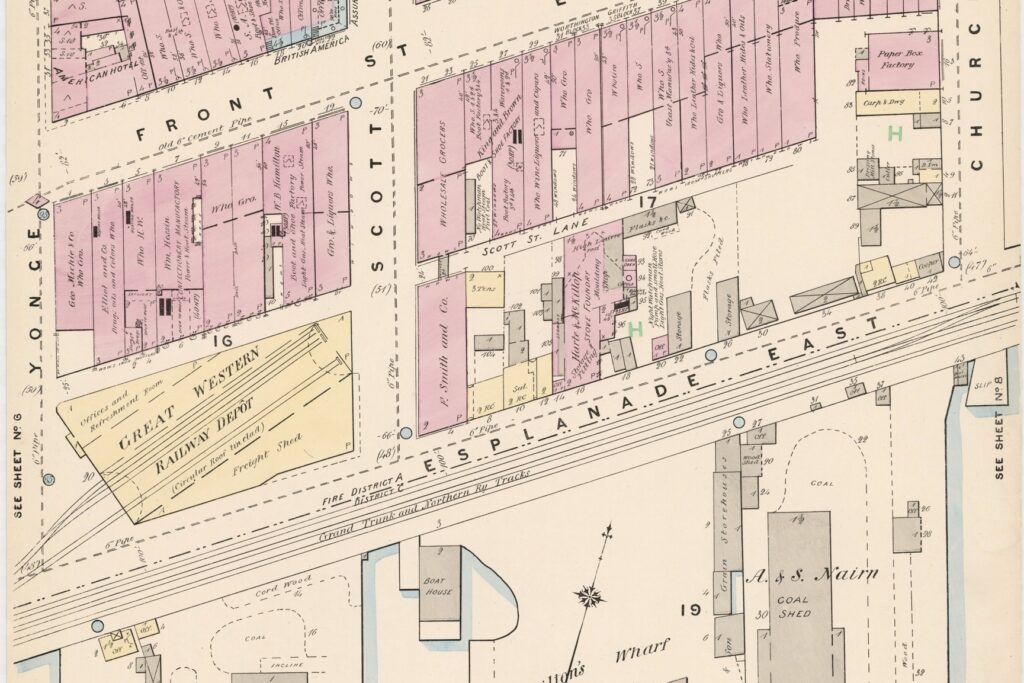

Train traffic increased faster than expected within the first year of operations over the Esplanade, and the original iron rails along that stretch had become worn enough to warrant replacement by the spring of 1860. It wasn’t long until more of the Esplanade was encompassed by the Grand Trunk, shrinking the space available for pedestrians and carriages in the process. The conditions on the eastern half of the Esplanade would be bad enough, but west of Bay Street the pedestrian access to the Esplanade would disappear almost immediately. In the late 1850’s, the Grand Trunk Railway built a roundhouse on top of the Esplanade next to Spadina Avenue, replacing an earlier locomotive repair and storage facility near the Don River. On August 25th, 1863, the Grand Trunk retroactively paid the city $35,000 for the lands now occupied by this roundhouse. In return, the city also granted the Grand Trunk the right to lay more tracks between Spadina Avenue and Peter Street “to the full extent that their business may from time to time render necessary”.

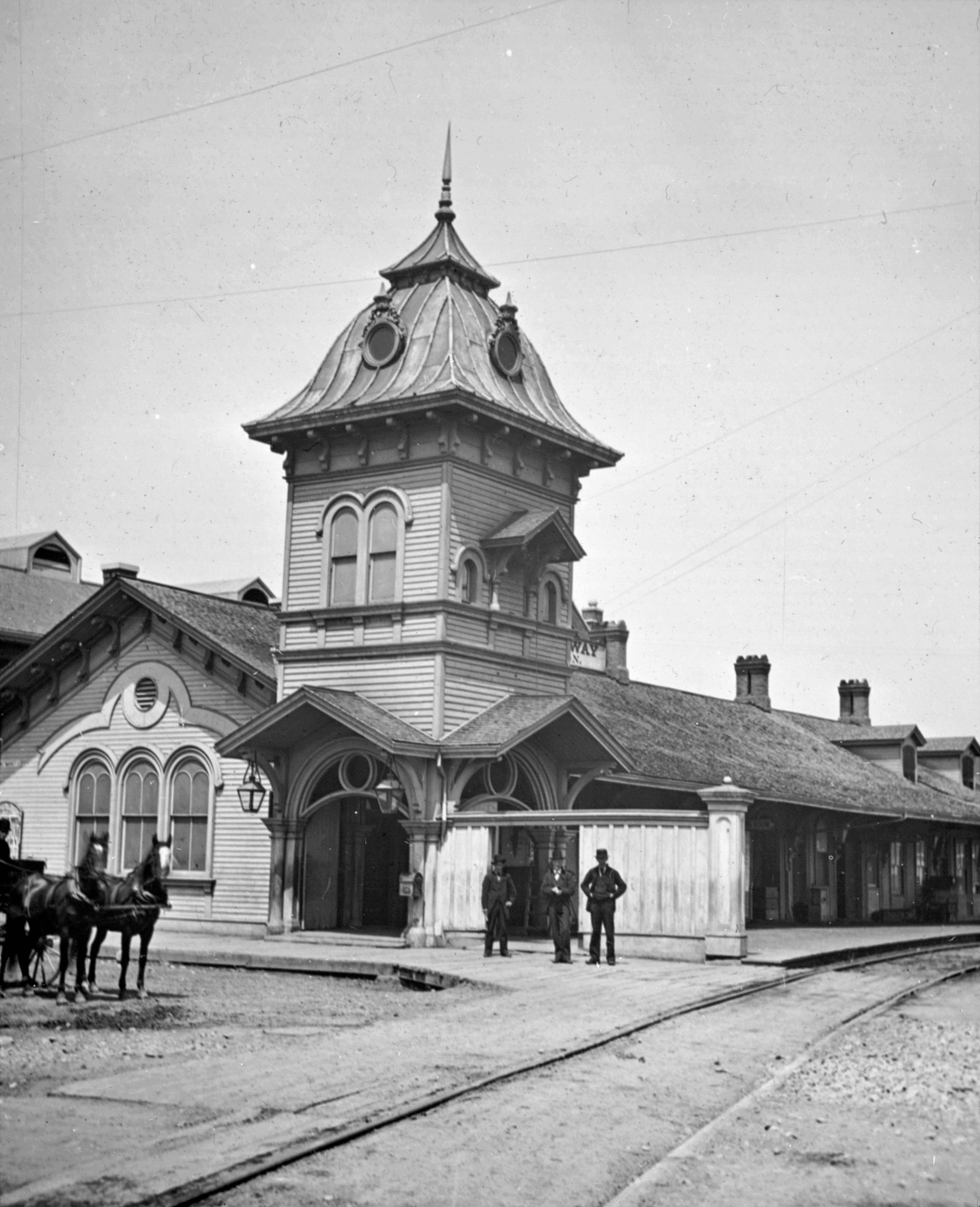

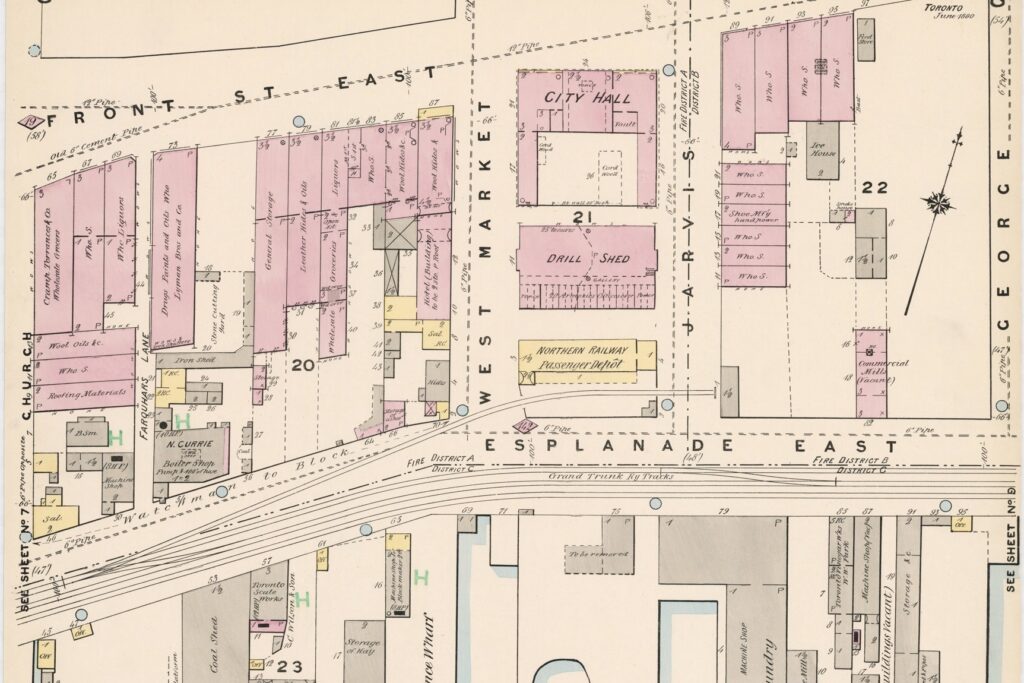

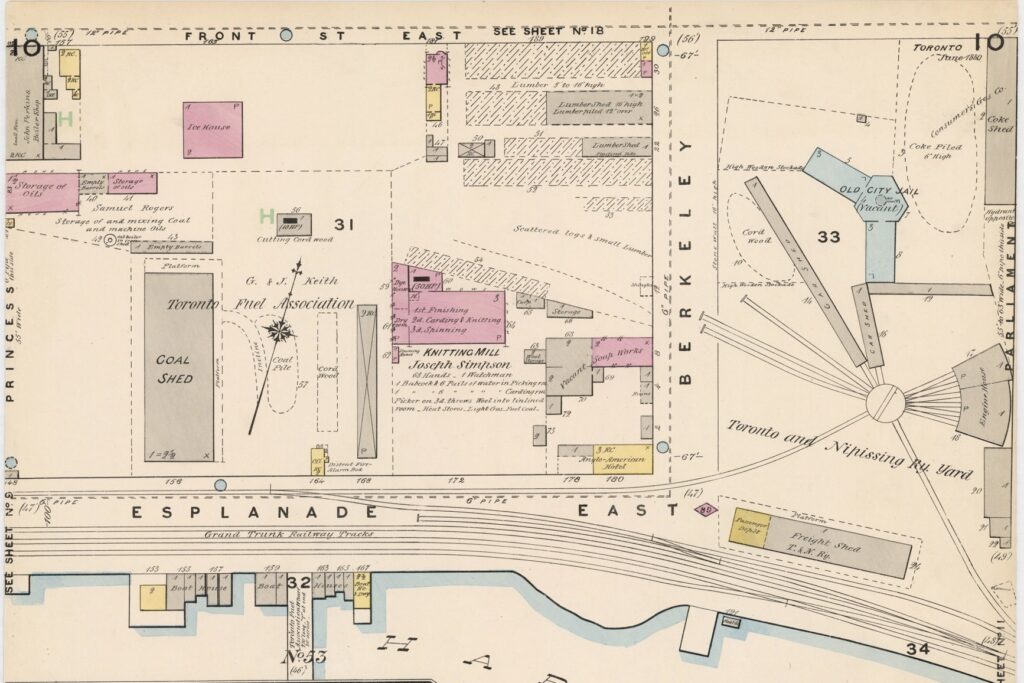

As Union Station began to suffer from overcrowding issues, the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron, now called the Northern Railway of Canada, would be the first to vacate it for a separate passenger facility west of Spadina in 1860. The Great Western Railway would follow suit several years later and establish a new passenger terminal firmly in the middle of the Esplanade on March 2nd, 1866. This new stub-ended station was located at the intersection of the Esplanade and Yonge Street, just under a kilometre east of Union Station. The Northern Railway would join them on the Esplanade the following year, opening a new passenger station of their own a few blocks further east at Jarvis Street in 1867. Only a few years later, the Toronto & Nipissing Railway would establish its terminal facilities at the far east end of the Esplanade ahead of that railway’s opening in 1871. A passenger station and roundhouse were built on a parcel of land between Berkeley Street and Parliament Street, located immediately to the west of the Gooderham & Worts Distillery. The Toronto & Nipissing was the only 3’ 6’’ narrow-gauge railway to occupy the Esplanade, and to reach this point it laid a third rail inside of an existing 5’ 6’’ broad-gauge track of the Grand Trunk Railway.

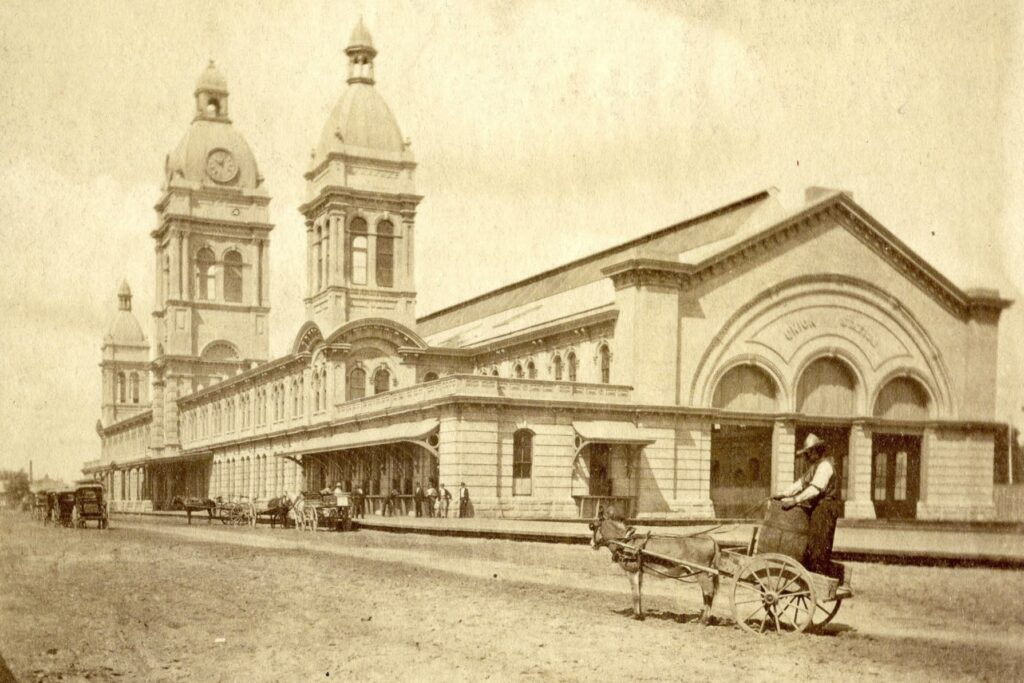

On May 15th, 1866, the City of Toronto sold an area just south of the existing Union Station to the Grand Trunk Railway so they could construct a larger passenger terminal. The old Union Station was torn down in 1871 and the new station was finally opened on July 1st, 1873. At the time of its completion road traffic was still permitted on the Esplanade west of Bay Street, but no further than Simcoe. The area west of that point had become occupied by mainline tracks, freight sidings, and a large freight house that the Grand Trunk had constructed in 1870, rendering it completely impassable. The section of the Esplanade adjacent to the new Union Station was bound by one of its walls on the north, and by three bypass tracks of the Grand Trunk, Great Western, and Northern railways on the south. To reach the new Union Station, the Toronto & Nipissing proceeded to lay its narrow gauge rail inside that of the Grand Trunk across almost the entire length of the Esplanade. The Grand Trunk would convert their system to 4’ 8.5’’ “standard gauge” later the same year, and until 1881 the Esplanade would be home to a mix of narrow, standard, and broad gauge tracks all at the same time. It was only during that year that the standard gauge became adopted by every railway in Toronto.

Throughout the 1880’s, all of Toronto’s railways were consolidated into either the Grand Trunk or the Canadian Pacific Railway as they each sought to gain the upper hand. The Grand Trunk, whose Union Station was now facing the same overcrowding issues of its predecessor, proceeded to keep the former Northern Railway station on the Esplanade open to offload some of the pressure. The former Great Western station at Yonge Street was converted into a freight facility, as was the former Toronto & Nipissing station at Berkeley Street. It was at this point in time that the inconvenience caused by the railways’ relentless expansion on the Esplanade reached a fever pitch. The Grand Trunk had offered to address these concerns as early as 1883, but as could be expected their solutions only involved further expansion. New freight yards would be built at the Don River and Danforth to ensure freight traffic on the Esplanade could keep moving efficiently. Additional tracks – which would be added to the three that now occupied the Esplanade by this point – were being considered for higher throughput, along with an expansion of Union Station. However, none of these addressed one of the primary concerns with the Esplanade, which was the safety of pedestrians. Even though trains were restricted to a speed of 6 kilometres per hour (4 miles per hour) on the Esplanade, injuries and deaths caused by train traffic were becoming more common. According to a letter written by Frederick Cumberland on July 22nd, 1889, the very use of the Esplanade for railway traffic was “unwise in the last degree, and justified by neither common sense nor professional opinion”. That year, several engineers submitted their plans to the City of Toronto to solve the Esplanade problem. One of the more practical plans involved a steel viaduct above the Esplanade, allowing the entire space underneath to be opened up for pedestrians. While it’s unknown exactly what this would have looked like, the plan sounds similar to the steel viaduct used as part of the Fort Street Union Depot in Detroit, Michigan, which itself only began construction two years after this Esplanade proposal was made. Among the more outlandish plans was one from 1890 that would have involved all passenger and most freight traffic to pass through a double-track tunnel beneath Front Street. All plans were ultimately rejected by one or both of the railways involved, citing cost and practicality.

Canadian Pacific happened to be in the process of securing an eastern entrance into the city, which involved laying two tracks along the south side of the Esplanade in 1892. On July 26th of that year, both the Canadian Pacific and Grand Trunk agreed to expand Union Station and its surrounding rail corridor. The total number of mainline tracks occupying the Esplanade was now five, and the addition of industrial sidings in subsequent years would bring this number to six or more in some places. The Esplanade’s western end was now shortened even further to York Street to make way for the additional station platforms. With the Esplanade now a foregone conclusion, city officials tried pushing for a new Esplanade south of the rail corridor. This came to partial fruition in the form of Lake Street in the late 1890’s, now called Lakeshore Boulevard. The street was built on new fill just south of a large lot owned by Canadian Pacific, to become the site of their John Street yards in 1897. New bridges at John Street and York Street were to be built at the expense of the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific companies respectively, in order to connect Lake Street with Front Street.

An Intolerable Situation

“The situation as it exists [on the Esplanade] at present is simply intolerable, and cannot be allowed to continue. That point should be clearly established before the Board of Railway Commissioners”.

The Toronto World, October 30th, 1907

The expansion of Union Station, if it solved the overcrowding issues at all, only did so for an incredibly short time. According to an issue of The Railway and Shipping World from 1899: “…the general consensus of opinion is that the Toronto Union is one of the most inconvenient stations in [North] America, expensive to run and unsatisfactory in very many other respects”. The safety issue caused by grade crossings along the Esplanade continued to get worse, especially closer to downtown. The Bay Street crossing was now intersected by nine tracks, more than almost any other street crossed by the Union Station Rail Corridor. The issue was further exacerbated by the arrival of the Canadian Northern Railway which began serving Union Station on November 19th, 1906.

The slow abandonment of railway operations on the Esplanade has much to do with the construction of Toronto’s current Union Station. After the Great Fire of 1904 carved out a large swath of land adjacent to the rail corridor, the Board of Railway Commissioners authorized the Grand Trunk Railway to expropriate that land for a new Union Station on February 23rd, 1905. Agreements between the Grand Trunk, Canadian Pacific, and Toronto’s municipal government in regards to the station headhouse were settled by April of the same year. It was initially expected that the new station would also be served by the Canadian Northern Railway, but they would refocus their efforts on a joint passenger terminal with Canadian Pacific at North Toronto shortly thereafter. An issue of the Canadian Manufacturer from March 2nd, 1906 reported that the contracts for its construction were awarded jointly by both railways involved, and the same article optimistically predicted that the new station would be completed by February 1908. As it turns out, the same debate over what should be done about the rail corridor from decades earlier would significantly delay progress on that front. A City Engineer’s Report from 1907 recommended a new corridor be built on a viaduct, to run parallel along the south side of the Esplanade. On May 24th of that year, the dangers posed by the existing rail corridor on the Esplanade came to a head with the highly publicized death of James Fraser, an engineer of the steamship Corunna, who was killed in a collision with a train at the Bay Street crossing. Following up on the incident on May 27th, the Toronto World published a scathing condemnation of the safety issues caused by the railways. The following is an excerpt from that piece:

“Does not the killing of the engineer of the Corunna at the Bay-street crossing indicate that Torontonians are a peculiar people in more ways than one? Poor dead man, he was from Scotland and not peculiar; but had he been Toronto born and bred, he might have dodged the engine, as so many Torontonians do every day in the year”

…

“Who of us, in the final analysis, may escape the brand of Cain, if we do not urge, work for and vote for the abolition of the level crossing? If every citizen played his part, the level crossing would soon be a matter of history. Until he does, the brand of Cain is on us”.

The Board of Railway Commissioners approved the city’s viaduct plan two years later in 1909, but a new layer of complexity was added soon afterward. The Toronto Harbour Commission was formed in 1911 and one year later developed plans to extend the waterfront by up to half a kilometre in some places at a cost of $19 million. A new agreement was reached in 1913 that involved moving the new rail corridor much further south on the water lots that the harbour commission was expected to fill.

Construction of the new Union Station began in 1914 but the onset of World War One later that year would greatly delay any further progress on both the station and the rail corridor itself. The parties involved all wished to prioritize grade separation, but disagreements continued over how this should be done. The railways wanted bridges to be built over the new rail corridor at the city’s expense. City officials preferred the rail corridor be elevated above the height of the surrounding roads, and that the railway companies pay for it themselves. The new Union Station building was completed in 1920 but work on the rail corridor hadn’t even begun yet. The discussions persisted even as Canada’s railway landscape encountered its biggest change in decades. As the Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk systems faltered, they were both nationalized in 1917 and 1920 respectively. The systems were officially combined into the Canadian National Railways, a new federal crown corporation, in 1923. In July 1924, a government-appointed arbitrator recommended that the 1913 agreement proceed, with the exception of new cost-saving measures to appease the railway companies. For example, rather than a steel viaduct, the rails would now be built on an earthen embankment. The railways accepted the modifications, which would save approximately $6 million in construction costs. Construction of the new rail corridor would finally begin on July 17th, 1925.

This change would have significant implications for railway activity on the Esplanade in the coming years. Despite lacking platforms or even the corridor itself, the new Union Station was officially opened on August 6th, 1927. A train led by Canadian National 6120 brought His Royal Highness, Edward, the Prince of Wales along the Esplanade to the opening ceremony. Work had already begun to alter the tracks on the Esplanade once mainline traffic was rerouted. Most of the area would remain occupied by tracks to serve the surrounding industries, requiring sidings and team tracks for the loading and unloading of freight cars. The Esplanade’s tracks would be severed west of Yonge Street, though a connection to the elevated corridor would be maintained at the Esplanade’s east end. The last through train would have unceremoniously made its run over the Esplanade at some point before the viaduct officially opened to traffic on January 21st, 1930.

The End of Rail on The Esplanade

Industrial switching would now define railway operations on the Esplanade from this point on. At the west end, the team tracks at Yonge Street would regularly be filled with freight cars owned by Pacific Fruit Express. These were intended for the Toronto Fruit Market, which was opened in the former Great Western station after the Grand Trunk vacated it. As was the case when it reached the Esplanade in the 1890’s, Canadian Pacific served the industries along the south side. The Grand Trunk’s claim to industries on the north side was inherited by Canadian National.

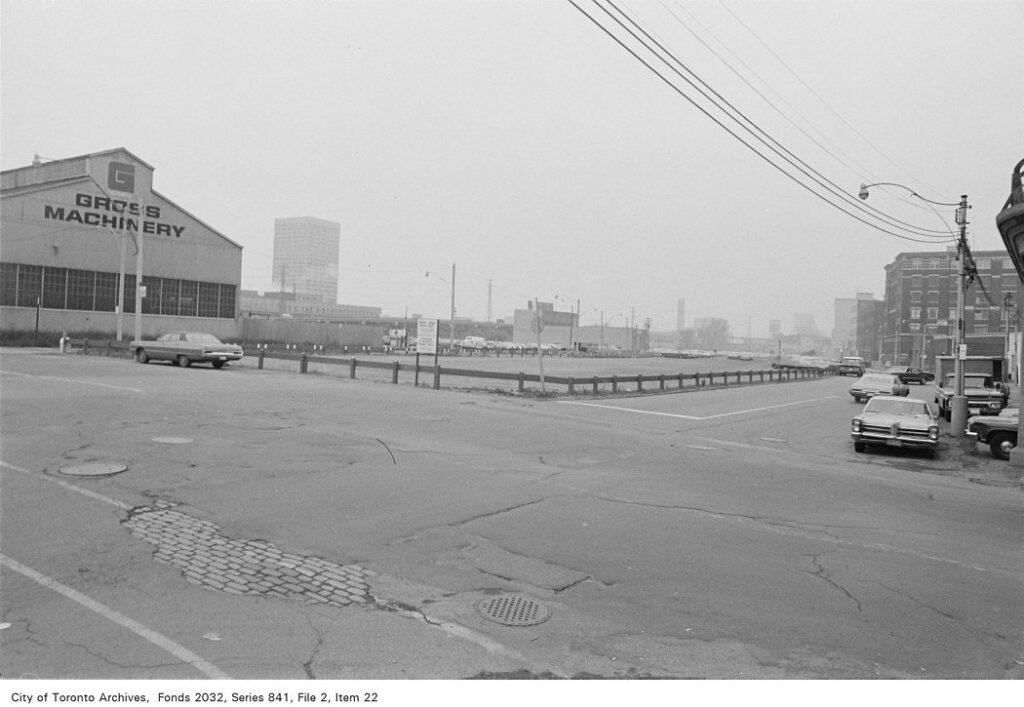

The situation on the Esplanade would change once more as industries began to leave the area in the postwar era. Toronto and its surroundings were also in a period of transition as automobiles became a primary mode of transportation. As car ownership skyrocketed after World War Two, urban freeways like the Gardiner Expressway and Don Valley Parkway were built to meet that demand in 1958 and 1961 respectively. The demand for parking rose equally, resulting in new zoning regulations. Over the next few decades, a significant amount of space near downtown was freed up for surface parking lots. When tracks on the Esplanade were ripped out, parking spaces usually took their place. The first major removal of tracks occurred from Yonge Street to Church Street in 1957. They were cut back even further to Lower Jarvis Street around 1970, though photographs from the time show cars were already parking on the tracks before they were removed. By 1975 the tracks had receded to Lower Sherbourne, then again to Parliament Street in 1977. The last segment of track on the Esplanade remained in front of the stone distillery building of Gooderham & Worts, which itself had been a fixture of the Esplanade and a customer of its railways since 1859. Rail service to Gooderham & Worts ended in 1986 but the rails remained in place into the 1990’s.

It would seem as though the Esplanade was lost once more, this time to the automobile instead of the iron horse, until efforts to revitalize the area were commenced under Mayor David Crombie during the 1970’s. Properties which were historically occupied by heavy industry now facilitated apartment complexes and mixed-use buildings. The middle stretch of the Esplanade was turned into greenspace, finally achieving the beautification its creators had originally set out to accomplish. The revitalization of the Esplanade has received significant praise, and a 2013 article from the Globe and Mail described it as “the best example of a mixed-income, mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly, sensitively scaled, densely populated community ever built in the province”.

Written by Adam Peltenburg.

References

Boles, D. (2009). Toronto’s Railway Heritage. Arcadia Publishing.

Maclear & Co. 1856. “Agreement between the city of Toronto and the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada for the construction of the company’s tract along the front of the city.” https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.50170/8?r=0&s=1.

Grand Trunk Railway. 1858. Proceedings of Fifth Annual General Meeting, Proceedings of the Fifth Annual General Meeting of the Shareholders of the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada. Montreal, Quebec: John Lovell, Canada Directory Office. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_00396_4/1.

Blackwell, Thomas, and John Robinson. 1860. Report of Mr. Thomas E. Blackwell, Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.22872/50.

Letters and Evidence Relating to the Right of the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada. 1880. Belleville. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.27285/5.

The Toronto World. 1883. “Traffic on the Esplanade.” October 16, 1883. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18831016/1.

Cumberland, Frederick. 1889. The Esplanade of Toronto. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.02237/5.

The Toronto World. 1897. “Railway Notes.” August 28, 1897, 12. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18970828/10.

“In the High Court of Justice.” 1899. In Union Station Agreement. Toronto: Warwick & Rutter. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.08928/9.

Parsons, W. B., C. B. Smith, and C. H. Rust. 1907. Report of Engineers, Report of engineers on the separation of grades in connection with the railway lines along the water front and on the proposed Union Station. Toronto, Ontario: n.p. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.84023/9.

“Captains of Industry.” 1906. The Canadian Manufacturer 52, no. 5 (March). https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_04937_581/26.

“Toronto Viaduct and Union Station.” 1912. The Railway and Marine World, (June). https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06958_78/22.

LeBlanc, Dave. “35 Years on, St. Lawrence Is a Template for Urban Housing.” The Globe and Mail, February 6, 2013. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/home-and-garden/architecture/35-years-on-st-lawrence-is-a-template-for-urban-housing/article8296990/.