The 125th Anniversary of the driving of the last spike on the CPR!

Click on each picture for a closer look!

Click on each picture for a closer look!

.

November 7, 2010 marks the 125th anniversary of the driving of the Canadian Pacific Railway Last Spike at Craigellachie, British Columbia in 1885. Nowhere else in the world has a private railway company been so inextricably linked to nation building as the CPR was to Canada. Binding the nation together by rail was one of the conditions of Confederation in 1867. When British Columbia joined the union in 1871, Canada agreed to build a rail line all the way to the Pacific coast.

By 1876, the Intercolonial Railway connected Central Canada with the Maritime Provinces. The line to British Columbia was much more problematic as it traversed 3,000 miles of vast, mostly uninhabited wilderness. After several false starts, the present Canadian Pacific Railway Company was incorporated in February 1881. By the end of that year, CPR hired American-born William Cornelius Van Horne as general manager of construction.

It was Van Horne’s drive and determination that would make possible the construction of the railway between Montreal and Port Moody, BC. The engineering challenges were numerous and included the penetration of the formidable Rocky Mountains, one of many mountain ranges that would have to be traversed. The political and financial challenges were equally as daunting with the company on the verge of bankruptcy throughout construction. This astonishing feat was accomplished in 4½ years, a timeline even more remarkable when one considers the sixteen years necessary to build Toronto Union Station and its approach tracks in the 1920s or, even more recently, the comparatively modest rebuilding of the St. Clair streetcar line, which took over five years.

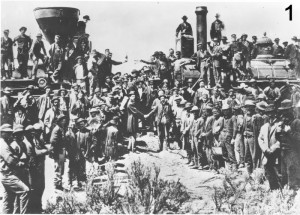

The significance of a last spike ceremony had to do with the fact that the railway was being built simultaneously in separate sections from the east and west. When those two sections met up and the railway was complete, an appropriate observance was held to commemorate the event by laying the last rail and driving in a ceremonial spike signifying the joining of the sections. A similar event was held in 1869 when the tracks of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads were joined at Promontory Point, Utah and the United States finally had a continuous railway line from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The photograph of that event had already become as iconic in U.S. history as the CPR photograph would be in Canada.

The U.S. event had involved hundreds of people being brought in on special trains, two gaily decorated locomotives touching pilots, a last spike made of gold, and much merriment and consumption of alcohol. However, given the financial vicissitudes of the CPR, Van Horne was determined that the Canadian ceremony would be considerably more austere. There was an attempt to involve Lord Lansdowne, the Governor-General of Canada, in the event since he was on a western tour, but his touring schedule was not compatible with the construction timeline.

In Montreal on the evening of October 27, 1885, Van Horne boarded his private car Saskatchewan for the trip to Eagle Pass, British Columbia where the ceremony was to take place. Also on board was Donald A. Smith, a CPR director who would actually drive the ceremonial spike. Various other officials were picked up along the way west, including Sandford Fleming in Ottawa. Fleming had been chief engineer of the Intercolonial and involved in the construction of Toronto’s first railways in the 1850s. He had even been present at another historic ceremony in October 1851 signifying the construction of Toronto’s first railway, the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron.

On Saturday, November 7, 1885, Van Horne’s train arrived at Eagle Pass. The site of the ceremony was a few miles west and Van Horne decided to give this location a name: Craigellachie, after a location in Scotland where an ancient clan battle had stirred his imagination. The overcast weather suited the austerity of the occasion as the various officials assembled for the ceremony in front of photographer Alexander Ross’s camera.

Van Horne decided that it would be CPR director Donald Smith who would actually drive the ceremonial spike. Smith was a cousin of CPR president George Stephen who was in England busy attending to the company’s precarious financial condition. Smith swung the maul, but only delivered a glancing blow and bent the spike, which was quickly replaced. On his second attempt, Smith connected and then held still for the photographer. Van Horne was called upon to make a speech and did so in his characteristically economical fashion with fifteen words, “All I can say is that the work has been well done in every way.” The officials then boarded their train, which proceeded westward towards Port Moody and the Pacific coast.

Van Horne’s short speech was somewhat disingenuous since much of the recent construction had been hasty and of a temporary nature. Furthermore the railway was not prepared to operate during the harsh winter weather that was about to descend on the mountain ranges. In fact, it was June of 1886 before the track work was sufficiently improved for the railway to begin transcontinental passenger train service.

Over the next few decades the Canadian Pacific Railway Company evolved into one of the world’s great railways as well as a worldwide transportation network. The company continued to be involved with important events in Canada’s history: settling the western Prairies, promoting immigration, creating an international demand for Canadian tourism, accomplishing astonishing feats of transportation logistics during both world wars and sponsoring royal tours in an era when Canadians were still fiercely loyal to the crown.

For many years, the Canadian Pacific Railway Company was the largest and most powerful company in Canada. While it still remains a formidable corporate presence, the CPR doesn’t influence the lives of ordinary Canadians the way it did during the first half of the twentieth century. From the 1890’s until the 1950’s, the company was tightly integrated into the day-to-day lives of almost all Canadians. CPR holdings included the longest privately owned railway in the world, a fleet of luxurious ocean liners on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, a fleet of ocean-going merchant freighters, inland and coastal steamship services, an international airline, intermodal services and Canada’s biggest trucking company. Other Canadian Pacific holdings not directly related to transportation included a chain of luxury hotels and restaurants, a global express service, telegraphs, money orders, telecommunications, mining, smelting, metallurgy, oil, gas, timber, waste management, steel, agriculture, and real estate. The company also owns thousands of miles of rail lines in the United States, reversing the usual economic imperialism that characterizes our relationship with that country.

In 1988, the late CPR Historian Omer S.A. Lavallee related a story “about a traveler a half-century ago who came to Canada to investigate agricultural and investment possibilities in the Prairie provinces. Having crossed the Atlantic Ocean on a Canadian Pacific steamer, traveled from Quebec to Montreal on a Canadian Pacific train, registered at Canadian Pacific’s Place Viger Hotel in the latter city, he then visited the company’s Windsor Station headquarters to confer with CPR officers about the company’s active role in industrial, agricultural and mineral development, as well as its land, immigration and colonization operations.

His questions answered, he went downstairs to the Canadian Pacific Railway ticket office to send off some messages by Canadian Pacific Telegraphs and a few gift parcels by Canadian Pacific Express, and to purchase his rail tickets for travel onward to western Canada. “There you are, sir,” said the ticket agent, handing him an envelope full of tickets and reservation forms, “your train leaves tomorrow night at 8:00 PM.” Since the city was on “Daylight Saving Time,” the agent added, helpfully, “that’s Standard – railway – Time.” “Good God!” rejoined the traveler, “does the C.P.R. control the time, too?”

Canadian Pacific’ imprint on Toronto was considerable and a number of significant landmarks were built here. Some of them have disappeared but many still remain, including Union Station and the rail corridor, the Royal York Hotel, the CPR Building at King and Yonge streets, North Toronto Station, Don Station and, of course, the John Street roundhouse, now the home of the Toronto Railway Heritage Centre.

The railway’s own public relations department was highly effective in promoting the mythology of the CPR. Railway employees continue to generate a variety of books celebrating the company’s history, including a compilation of CPR’s colourful advertising. But the railway had plenty of help keeping the mythology alive. One would be hard put to find a one-volume history of Canada that did not include the photograph of the Last Spike.

CPR found several opportunities to celebrate the Last Spike during anniversaries of the event. In 1936, the 50th anniversary of the first transcontinental passenger train, the railway created a blaze of publicity with special trains and new equipment. The 60th anniversary in 1945, along with the end of World War II, was also an opportunity for celebration and a reenactment of the ceremony was staged in Revelstoke.

In 1952, E.J. Pratt, Canada’s most famous poet, published his epic poem Towards the Last Spike. This was an era in which people still purchased poems in separate hard cover volumes and the book was a best seller.

On November 6, 1960, the Canadian Railroad Historical Association celebrated the 75th anniversary of the Last Spike. Lacking the means to travel to BC, the CRHA sponsored an excursion from Montreal to St. Lin, Quebec, where a reenactment of the ceremony was staged. Hauling the train was steam locomotive No. 29, built by the CPR just two years after the actual ceremony.

As poetry gave way to music as the primary lyrical medium, singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot performed his Canadian Railroad Trilogy on New Year’s Day in 1967 to help celebrate Canada’s Centennial. The song specifically commemorated the building of the CPR while at the same time acknowledging the hardships of the anonymous men who built it. According to Lightfoot, Pierre Berton said to him, “You know, Gord, you said as much in that song as I said in my book.” In 2010, Lightfoot teamed up with artist Ian Wallace to create a children’s book illustrating the lyrics of the ballad.

By far the most effective promotion of CPR’s mythological stature was the publication in the 1970s of Pierre Berton’s The National Dream and The Last Spike. In 1973, CBC Television broadcast a mini-series dramatization of the books. The books and the television show were both extensively analyzed in an earlier article on this website.

In 1985, CPR celebrated the centennial of the Last Spike in spectacular fashion. Special trains brought visitors to the Craigellachie and ex-CPR steam locomotive No. 1201, the last to be built by the company in 1949 was borrowed from the National Museum of Science & Technology in Ottawa. Reenacting the driving of the Last Spike was the 4th Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal, great-grandson of Donald A. Smith.

More recently in 2010, author Ray Argyle published The Boy in the Picture, about the young man shown at the centre of the Last Spike photograph. The initial launch of this book was at the Revelstoke Railway Museum, not far from Craigellachie. The Toronto launch was held at the Toronto Railway Heritage Centre in August 2010.

#1- The Golden Spike ceremony in the United States linking the Atlantic and Pacific was held in 1869, sixteen years before the CPR Last Spike. General manager W.C. Van Horne decided that the Canadian event would be considerably more modest with no politicians present for the ceremony.

#2- Before the more famous photograph of this event was made, photographer Alexander Ross recorded this image at 9:20 AM Pacific Time on November 7, 1885. Holding the maul is Donald A. Smith (later Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal). To the left of him is W.C. Van Horne, the general manager of the CPR and primarily responsible for the construction of the railway. Standing between them with the tall hat and white beard is Toronto engineer and inventor Sandford Fleming.

#3- Two minutes later at 9:22 AM, Ross recorded the more recognizable image of the Last Spike. To the right of Donald Smith is young Edward Mallandaine, the subject of Ray Argyle’s book The Boy in the Picture. Further to the right, the man with the goatee looking at the camera is supervisor of mountain construction James Ross, who had previously supervised construction of the Credit Valley Railway in Toronto and later helped build the city’s electric streetcar system.

#4- The actual spike used in the ceremony, which was mutilated to provide souvenirs to various officials. The spike was held by the Stratchcona family for many years, then donated to the Canada Science & Technology Museum in 1985.

David F. Rooney photograph

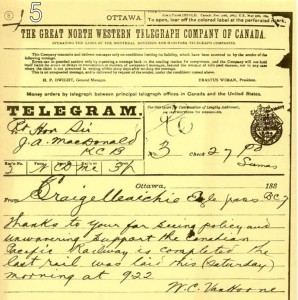

#5- The telegram sent by Van Horne to Sir John A. Macdonald. The prime minister’s support had not been quite as unwavering as the CPR would have preferred in the months leading up to the Last Spike.

From Building the CPR jackdaw collection

#6- W.C. Van Horne’s private car Saskatchewan, which carried him from Montreal to Craigellachie and on to Port Moody once the ceremony was over. The car is seen here in 1894 near the Stoney Creek bridge in the Selkirk Mountains. Van Horne is on the right, sitting on the platform. A week later he was knighted and became Sir William. The gentleman sitting on the coupler is Torontonian Sir Casmir Gzowski.

From Canadian Rail No. 375

#7- Saskatchewan is seen here at John Street some time during the early 1930s. The car is now at Exporail near Montreal and will figure prominently in the museum’s celebration of the 125th anniversary of the Last Spike.

From Canadian Rail No. 375

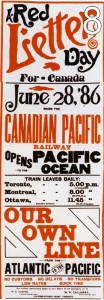

#8- Regular transcontinental passenger service began in June 1886. This poster ignores two important facts. Torontonians had to travel almost as far east as Ottawa before they could board a transcontinental train and the CPR would actually not reach the Atlantic Ocean for another three years.

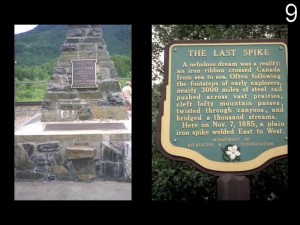

#9- The cairn and plaque at Craigellachie commemorating the Last Spike.

Google images

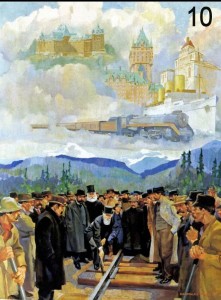

#10- CPR commemorated the event in 1945 with this artwork used on the front of dining car menus. Toronto’s Royal York Hotel is on the upper right. The artist has exercised some artistic license as James Ross is now looking at Smith instead of glaring at the camera, as he was in the photograph.

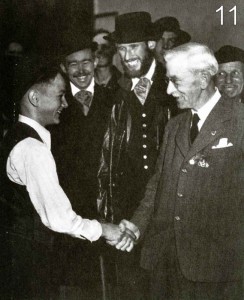

#11- A Last Spike reenactment was staged in Revelstoke in 1945. Edward Mallandaine was by this time the last survivor in the famous photograph and is seen here greeting the boy who played him in the reenactment. Mallandaine would live for another four years before dying in 1949 at the age of 82.

Photo from The Boy in the Picture by Ray Argyle. Original photo courtesy of the Revelstoke Museum.

#12- In 1952, E.J. Pratt published his epic poem Towards the Last Spike.

#13- On November 6, 1960, the CRHA chartered a special excursion from Montreal to St. Lin, where a reenactment of the Last Spike ceremony was staged.

Fred Angus photograph from Canadian Rail

#14- Gordon Lightfoot’s epic ballad, The Canadian Railroad Trilogy was released in his 1967 album, The Way I Feel.

#15- Pierre Berton’s The Last Spike was published in 1971 and has been in print ever since. The current edition of the book features W.C. Van Horne on the front cover.

#16- Undoubtedly the Last Spike ceremony reenactment with the most visual authenticity was this version staged for the CBC Television production The National Dream in 1973, although it was filmed only 30 miles from Toronto.

#17- The current Lord Strathcona drives the spike at the reenactment in 1985 as his great grandfather did 100 years earlier. Behind him wearing a beret is CPR Historian and author Omer Lavallee. Stratchcona donated the bent spike that had been in his family’s possession to the people of Canada.

From Canadian Rail No. 391

#18- A last spike ceremony was also staged for the opening of Leon’s furniture store at the John Street Roundhouse in 2009. Wielding the maul is Toronto mayor David Miller.

Norm Betts

#19- The Toronto launch of Ray Argyle’s young adult book, The Boy in the Picture was held at Don Station at the Toronto Railway Heritage Centre in August 2010.

Click here to read the next of our series of TRHA News postings on the 125th Anniversary of the driving of the Last Spike on the CPR.

.

Posting by Derek Boles, TRHA Historian

.