Not to be confused with the Great Western Railway in the United Kingdom.

Introduction

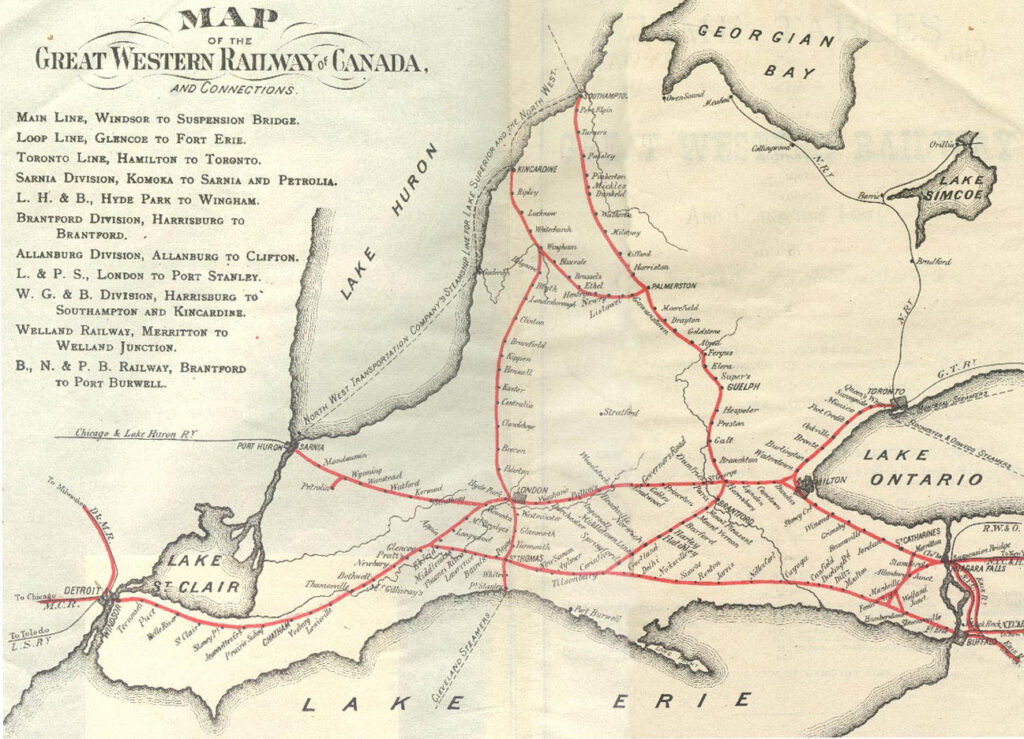

The Great Western Railway was the first railway chartered in the province of Upper Canada, albeit originally under a different name. It achieved a great number of accomplishments over its 29-year operating history. For example, it was the second steam railway to open in this province and the third to reach Toronto, beaten to the titles of first and second respectively by a matter of months in both instances. At its greatest extent, the Great Western reached a length of 1,371 kilometres (852 miles) from Windsor and Sarnia in the west, to Toronto, Niagara Falls and Fort Erie in the east, and to Kincardine and Southampton in the north. It was originally intended as a “bridge route” that shortened the distance for rail traffic travelling between New York and Chicago, with interchange traffic making up nearly half of the railway’s revenue at times. While the Great Western was absorbed by the Grand Trunk Railway in 1882, parts of its legacy can still be found today. Some railway lines established by the Great Western Railway over 170 years ago remain in use as important thoroughfares for Canadian National, VIA Rail, GO Transit, and Amtrak. Some of its buildings have also managed to survive to the present day.

Breaking Ground in Upper Canada

The Great Western Railway’s beginnings trace back long before Canada’s railway boom began. Within two decades after the end of the War of 1812, local efforts to build a railway in Upper Canada started to materialize. The London & Gore Railroad was chartered on May 6th, 1834 to construct a railway between the towns of Hamilton and London, along with provisions for an additional line to the shore of Lake Huron. This made it the first railway company to be chartered in the Province of Upper Canada. For further points of reference, this occurred only two months after Toronto was incorporated as a city, and also two years before the first railway in Canada – the Champlain and Saint Lawrence Railroad – was completed. One of the individuals behind the London & Gore was Allan MacNab, a War of 1812 veteran, businessman and politician from Hamilton who would later be knighted for his efforts in quelling the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837. However, the political influence of MacNab combined with the wealth of its primary investor, Samuel Zimmerman, was not enough to initially get the London & Gore Railroad off the ground. Construction of the railroad stagnated for over a decade and it was beaten to completion by another railroad in Upper Canada, the horse-powered Chippawa and Queenston Railway in 1841.

After many years of inactivity, the London & Gore was re-incorporated as the Great Western Rail Road Company in 1845 just before the original charter lapsed. The similarity of its name to that of the existing Great Western Railway in the United Kingdom was no coincidence, but a tactic to attract wealthy investors from across the pond. The railway would later modify its name to the Great Western Railway in 1853, even more closely matching its European counterpart. Its headquarters was subsequently established in Hamilton, a settlement on Lake Ontario that was rapidly industrializing. Its total population was not much smaller than Toronto at the time, and MacNab’s involvement in local politics helped in its selection as a future hub for the railway. While Hamilton was spoken for, the railway’s Chief Engineer Roswell Benedict came up with a new route between Niagara Falls and Windsor. The idea was to interchange with American railroads at these points, providing a quicker route than if the railroads in question had to remain to the south side of Lake Erie. A groundbreaking ceremony was held in London on October 23rd, 1847, but progress would still be contingent on further funding. This would soon present itself in the form of a loan interest guarantee by the Province of Canada, which would eventually act as a double-edged sword for the fledgling railway.

Since railway development in Canada had fallen behind that of the United States and Britain, the government sought to financially incentivize the construction of railway lines in Canada. The Guarantee Act was passed by the Province of Canada in 1849, ensuring that interest on half of the railway’s bonds were eligible for a guarantee from the government once half of a given railway line was complete. Eligibility was also determined by the length of the railway, which had to be at least 120 kilometers (75 miles) long. The Great Western was one of a few companies that took advantage of this guarantee, and construction soon began between Hamilton and London. However, a controversial condition would be added to the loan interest guarantee a few years later. The Board of Railway Commissioners, formed by the Province of Canada in 1851 to administer the guarantee, decided in 1852 to require all eligible railways to use 5-foot 6-inch “Portland gauge”. This differed from the 4-foot 8.5-inch “standard gauge” which was generally popular in the United States. It’s believed that this decision was heavily influenced by business interests in Portland, Maine, who were supporting the construction of their own railway to Montreal which had already adopted the so-called Portland gauge as a means to prevent competition from the port of Boston. British trading companies also stood to benefit if the Portland gauge was incentivized by restricting competing trade with the United States. From a national security standpoint, the gauge difference would theoretically hinder attempts to invade Canada by slowing down troop trains. This must have been at least a matter of some consideration given the last war with the United States had occurred just four decades earlier. In any case, the Portland gauge was chosen by the Board of Railway Commissioners and subsequently became known as “provincial gauge” in Canada.

The flat geography of the peninsula bound by Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair made construction relatively easy once it began in 1851, with the exception of ascending the Niagara Escarpment north of Hamilton. With construction of the line still underway, Zimmerman proposed to purchase the Erie and Ontario Railway and the Niagara Harbour and Docks Company in 1853. He threatened to buy these assets himself and operate them as a competitor should the board of the Great Western deny his proposal. MacNab’s position against the proposal set him at odds with the rest of the board, leading to his forced departure from the company shortly thereafter. As construction neared completion, the Great Western was unable to begin operating in time to beat the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway, which ran its first revenue train between Toronto and Aurora on May 16th, 1853. The Great Western Railway was finally able to run its first train between Hamilton and Niagara Falls nearly five months later on November 1st, 1853, with a further delay of nine days before regular service commenced between those points on November 10th. The remainder of the line from Hamilton to Windsor was finally opened by the start of the following year, and a grand ceremony was held in Hamilton on January 17th, 1854 to celebrate it.

Early Achievements and Expansion to Toronto

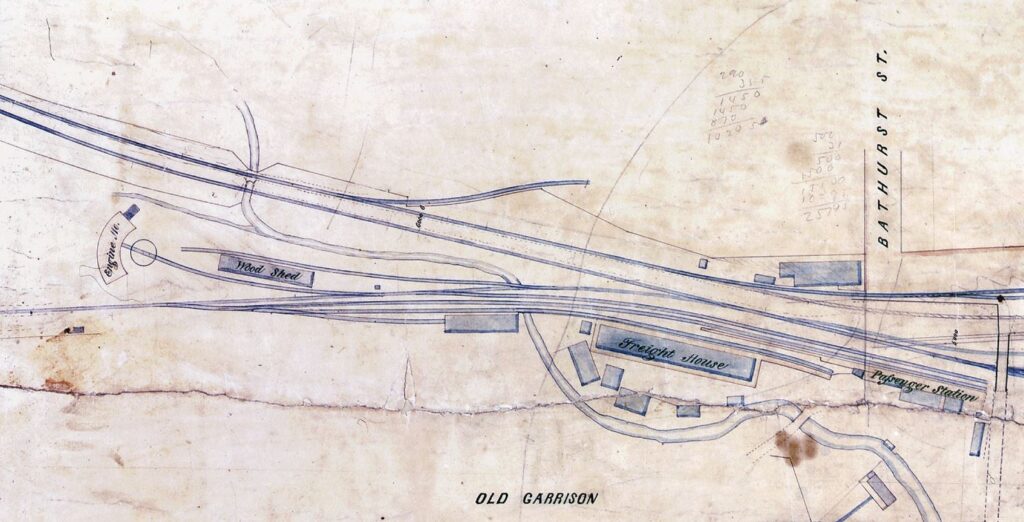

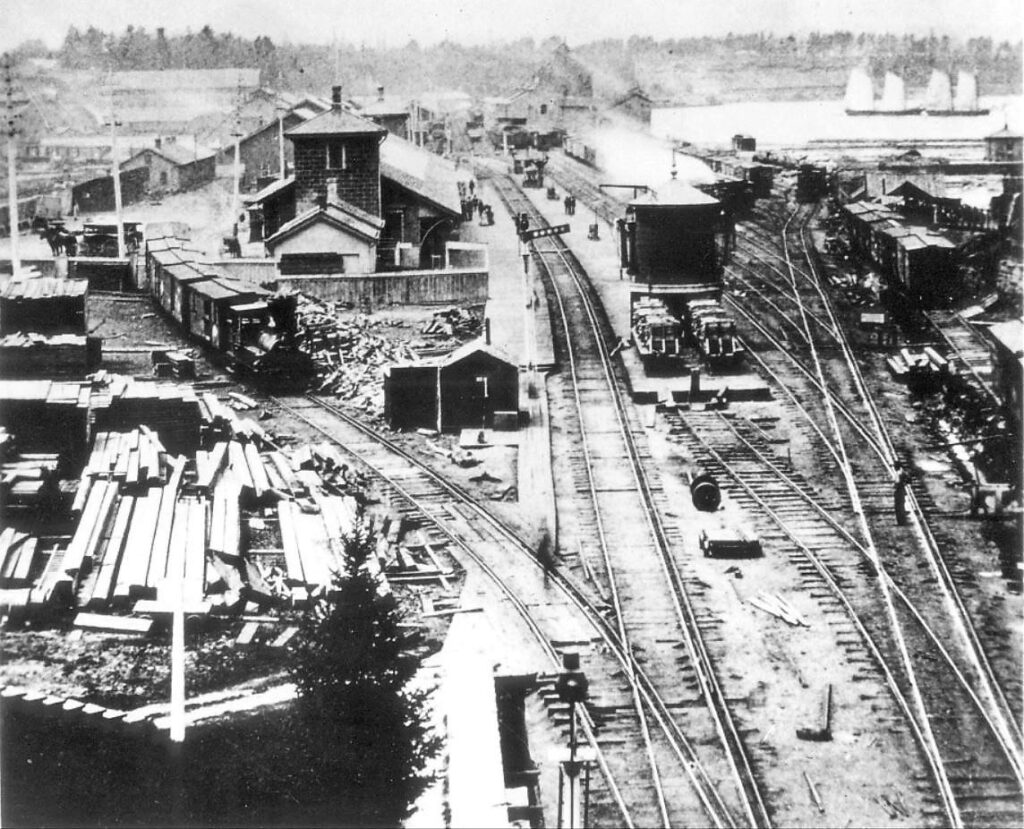

Efforts to construct a railway between Toronto and Hamilton began alongside the development of the Great Western. The two cities were in relatively close proximity to one another, and transit services in the form of stagecoach routes had already sprung up along the lakeshore between them. The Hamilton & Toronto Railway was initially chartered in December 1846 as an independent venture to connect the two cities, but the charter lapsed due to a lack of progress. Another company with the same name was incorporated in 1852 over the same route, possibly by individuals associated with the Great Western. In any case the Hamilton & Toronto was absorbed into the Great Western on October 4th, 1855 while its construction was still underway. The Great Western began accepting tenders for construction of a new rail terminal in Toronto on October 18th of the same year, to be built just north of Fort York on the west side of Bathurst Street. These facilities would include a passenger depot, a freight house, and a roundhouse among a variety of smaller auxiliary buildings. The first Great Western train arrived in Toronto on December 3rd, 1855, though an opening celebration was not held until three weeks later on December 20th. A banquet and grand ball was held in the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway locomotive and car repair shops at the foot of Spadina Avenue since there was no venue in the city large enough to accommodate the estimated 5,000 attendees. Hotel space in Toronto was so scarce that 100 beds were set up in St. Lawrence Hall for out-of-town visitors. Among the guests was Sir Edmund Head, the Governor-General and John A. Macdonald, Attorney-General and future Prime Minister. A wooden floor was built over the tracks and the shop was unrecognizable as such once the decorations, including a fountain, were put in place. The New York Times reported that “The company, which was gay and brilliant in the extreme, and boasted of many of America’s fairest daughters, did not break up until a late hour”. While the Great Western’s Toronto Branch would eventually become a major rail artery, at this point in time it was treated as a secondary branch line which complemented the mainline between Niagara Falls and Windsor.

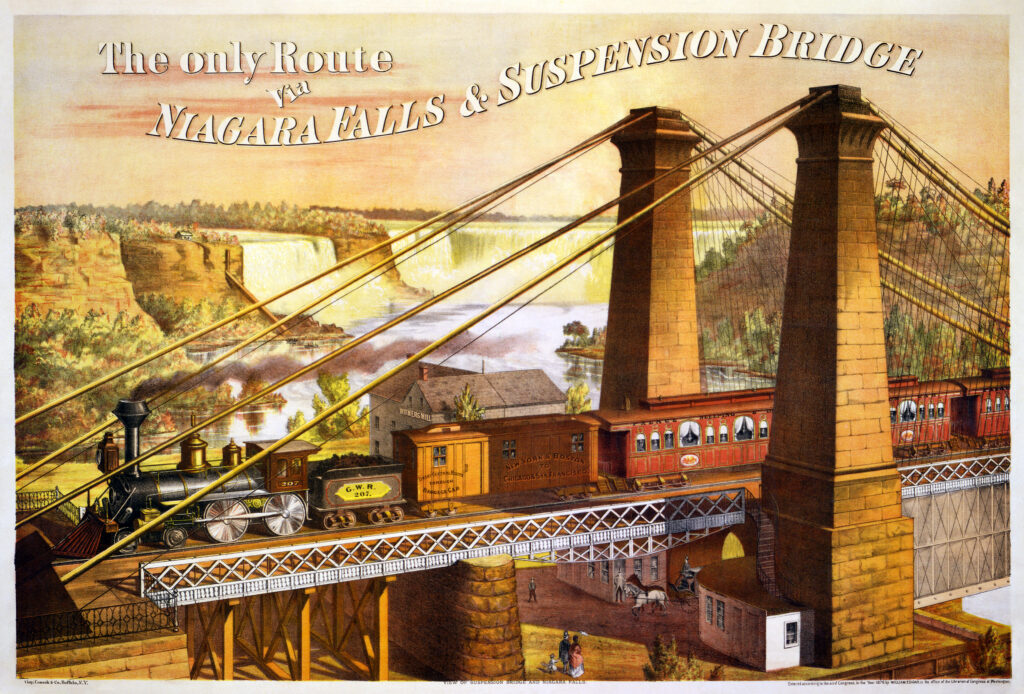

Even before construction of the Great Western Railway to Niagara Falls began, a suspension bridge across the 52-metre-deep Niagara River Gorge was envisioned by local politician William Hamilton Merritt. The necessary charters to build the bridge were approved by Upper Canada and the State of New York in 1846, years before the Great Western ever arrived in Niagara Falls. Engineers were then invited to submit their designs for the bridge. One of these engineers by the name of Charles Ellet Junior contacted Charles B. Stuart, chief engineer of the newly reorganized Great Western Railway, to gain their support. Ellet assisted Stuart in selling stock of the bridge companies and he was ultimately awarded the contract to build the bridge on November 9th, 1847. A temporary bridge was completed by Ellet on August 1st, 1848, designed to aid in the construction of a permanent bridge which would carry the railway. However, even though the bridge companies prohibited Ellet from collecting tolls from bridge users, he did so anyway and collected $5,000 over the course of several months. This led to a dispute between the bridge companies and Ellet, who was taken to court over the matter. Another engineer, John Roebling, was selected to replace Ellet in designing and overseeing the construction of the permanent bridge.

Roebling’s final design was a double-decker suspension bridge with train tracks on top and a road underneath for pedestrian and carriage traffic. While only wide enough for a single track, the bridge would be designed to carry three separate railway gauges simultaneously to correspond with each railway company on either side of the gorge. In addition to the 5-foot 6-inch gauge Great Western on the Canadian side, the American side had the narrower 4-foot 8.5-inch gauge New York Central Railroad and the wider 6-foot gauge Erie Railroad, both of whom were also interested in making use of the bridge. Concerns were raised by the public over the potential for collapse, to which Roebling responded by further strengthening the bridge with guywires. After testing the bridge with a 26-ton locomotive and 20 loaded cars, the suspension bridge was opened on March 18th, 1855. In addition to being the first railway bridge over the Niagara River, this was now the Great Western Railway’s first direct rail connection to the United States.

While the Great Western did reach many milestones in its early years, they were not without their fair share of tragedy. On March 12th, 1857, just four years after this section of the railway had opened, a Hamilton-bound passenger train from Toronto broke an axle while crossing a bridge over the Desjardins Canal just northwest of Hamilton. The bridge gave out and the train plunged 18 metres (60 feet) into the frozen canal below. With a total of 59 deaths, it was the single deadliest train accident in Canada at the time and remains third in that regard today. Among the dead was none other than Samuel Zimmerman, whose approval of shoddy construction practices for the railway may very well have contributed to this disaster. The Desjardins Canal bridge collapse was just one of many serious accidents that had occurred since the Great Western’s opening, though it was easily the most noteworthy.

Expansion, Competition, and Hard Times Ahead

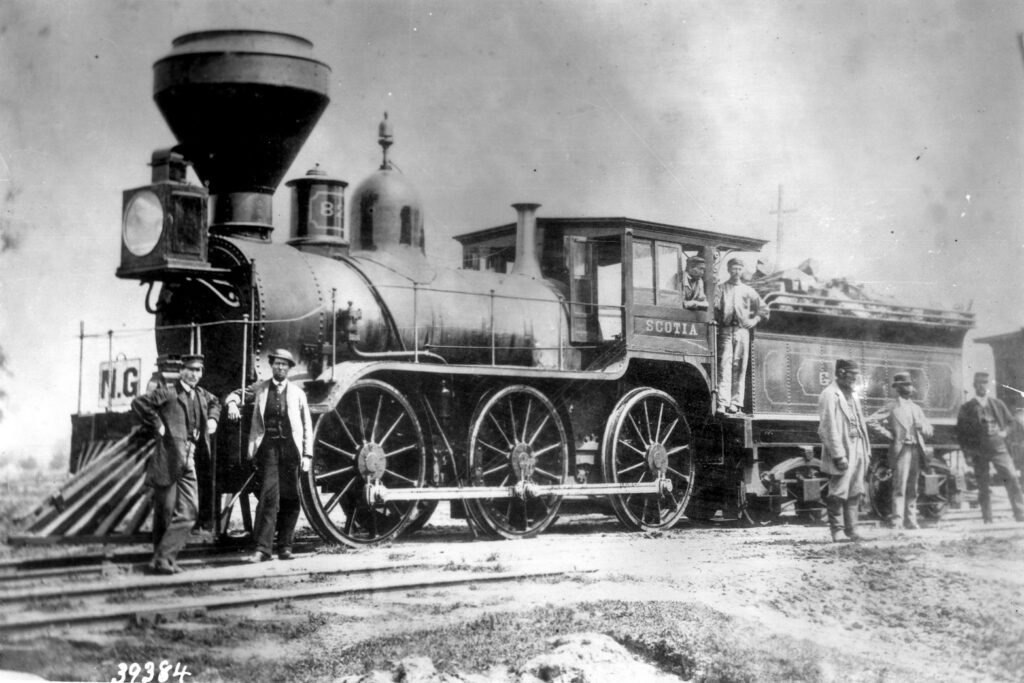

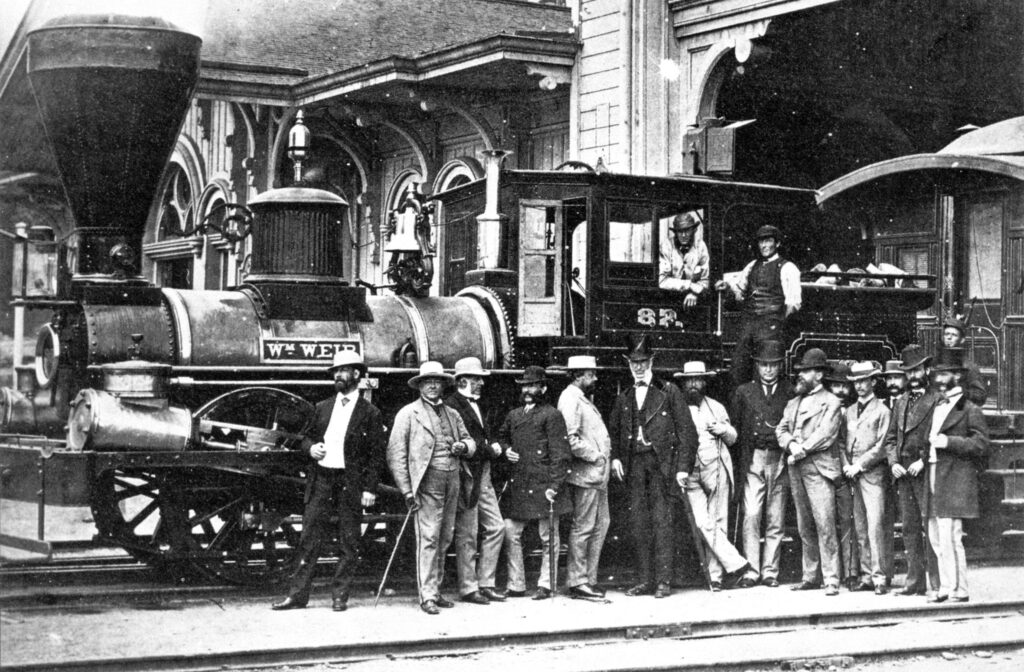

Repair shops were constructed in 1853 on 40 acres of land adjacent to the rail yards in Hamilton to keep the railway’s ever-growing fleet of locomotives and rolling stock in good condition. These sprawling facilities were also capable of constructing their own locomotives, which they did on several occasions due to a lack of local manufacturers. However, much of the Great Western’s early fleet were built in the northeastern United States or shipped overseas from Britain. By the end of 1856, the railway had a total of 86 locomotives and 1,786 pieces of rolling stock. In November 1858, the Hamilton Shops were responsible for constructing Canada’s first sleeping car for overnight trains. In 1861, they were also responsible for building locomotive no. 82, “Scotia”, which was the first locomotive in Canada equipped with a steel boiler. This enabled the use of coal as a source of fuel instead of cordwood, which had been the most common fuel in steam locomotives up to that point.

The Great Western’s near monopoly on southwestern Ontario was almost immediately broken up by the arrival of several competitors. The first was the Grand Trunk Railway, who were in the process of constructing a long-distance “trunk line” between Portland, Maine and Chicago, Illinois via Montreal and Toronto. It was built primarily to the north of the Great Western system, reaching Stratford in 1856, followed by St. Marys in 1858, and Point Edward in 1859. Point Edward is located just north of Sarnia, where the Great Western had expanded just eleven months earlier in December 1858. The two companies operated rival rail car ferries across the St. Clair River, which had to be used in lieu of a bridge due to engineering challenges. The rivalry between the two companies would extend into the United States with the Great Western’s purchase of the failing Detroit & Milwaukee Railway in 1860.

The consequences of the Great Western’s rapid expansion were felt during the 1860’s, further exacerbated by world events and poor financial decisions like the acquisition of the Detroit & Milwaukee. Doing so undermined its relationship with the Michigan Central Railroad, which was one of the Great Western’s primary interchange partners in Detroit. The breakout of the American Civil War in 1861 had far-reaching economic consequences for railroads in Canada, including the Great Western. Cross-border rail traffic had fallen substantially, and the lack of income during this period severely hampered expansion. Much of the Great Western’s tracks had to be replaced quite early on due to the hasty nature in which they were built. Between 1861 and 1865, the Chief Engineer of the Great Western called for repair expenditures of two million dollars. There were some efforts to merge the Great Western with the Grand Trunk and the nearby Buffalo & Lake Huron Railway to cope with the economic downturn, but nothing would ultimately come of this.

What little traffic the Great Western still had was often delayed by the process of loading and unloading goods at the US border due to the gauge difference. Thomas Dakin, President of the Great Western, along with company Director Thomas Faulconer, travelled from Britain to Canada in 1864 to inspect the railway and came to the same conclusion. After returning to England, Dakin argued in favour of laying a 4-foot 8.5-inch gauge third rail to circumvent the loan interest guarantee conditions during a meeting on October 5th of the same year, stating the following:

“It has been clearly demonstrated to the Board that the future prosperity of the Great Western Railway of Canada under the existing circumstances of surrounding competition is inseparable from the promotion of more expeditious and economical transport of through traffic than at present exists. There are several measures in contemplation for accomplishing this object, but the first desideratum is the securing of an unbroken gauge, so as to avoid the delay and expense of handling freight consequent upon the double transshipment in its passage through Canada, by laying an intermediate or third rail between the Canadian rail gauge of 5 ft. 6 in. and thus provide the American gauge of 4 ft. 8.5 in., as was originally intended when the G. W. R. of Canada was designed”.

Around 1866, the same year a new passenger station was built in Toronto, work also began on adding a third rail to the entire Great Western system. This was complete on its main corridor between Niagara Falls and Windsor by January 1st, 1867, and the first standard gauge rolling stock from Chicago to New York made its way through Canada over the Great Western on April 9th of the same year. The inaugural train included an excursion party inside the Pullman hotel car “Western World”. The allowance of through-traffic without the need for delays at each border was generally successful. After finally having the possibility of realizing the full potential of a bridge route between American railroads, the Great Western’s very existence was once more threatened with the founding of the Erie and Niagara Extension Railway in 1868. Its name was changed to the Canada Southern Railway in February of the following year, and it had intentions to build a faster competing line between Niagara Falls and Windsor.

Re-Gauging and Amalgamation

A mixed-gauge system was found to have numerous downsides in the long run, particularly in the maintenance of an additional rail. In 1870, a session of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada decided to remove the broad-gauge condition from the loan interest guarantee, and the Great Western became one of several railways in Canada to promptly convert their system in the years that followed. Already having a 4-foot 8.5-inch gauge rail in place in most areas, the existing broad-gauge rails were gradually removed between 1870 and 1873. The Toronto Branch was converted almost immediately in December of 1870, disrupting traffic for approximately eight hours due to the lack of a third rail on the branch. Simultaneously, the aging iron rails used by the Great Western up to this point were replaced with more durable steel that could better handle Canada’s cold winters. Just prior to the gauge conversion the Great Western had a total of 133 locomotives and 1,897 pieces of rolling stock, all of which had to be either converted to the new gauge or replaced. The last broad-gauge engines were built by the Great Western’s Hamilton Shops in late 1869, and it’s believed that the last one was scrapped in September 1875.

Expansion ramped up on the Great Western towards the end of the 1860’s. The Wellington, Grey & Bruce Railway was chartered in 1864 to connect the Great Western’s Galt and Guelph branch to the shore of Lake Huron. The sod was turned in 1867 with plans to have the line split off to two destinations on Lake Huron, namely Southampton and Kincardine. Given that this route was sought after by the Great Western, the hope was that they would lease the line. The Great Western did exactly that in 1869 while construction was still underway, and after operations began, they made an agreement to handle all traffic over the Wellington, Grey & Bruce in 1873. Three years later, the Great Western acquired the bonds of the company. It was essentially an extension of the Great Western system at this point, and appeared as such on maps from the period. In response to the potential competition from the Canada Southern Railway, the Great Western chartered the Canada Air Line Railway Company in July of 1869. It would break off the Great Western mainline at Glencoe, then generally running in an easterly direction to Fort Erie on the Niagara River. Between Fort Erie and St. Thomas, the Canada Air Line would run almost parallel to and within close proximity of the Canada Southern. Both railways would be complete in 1873, becoming two of the constituent railways to use the new International Bridge built by the Grand Trunk between Fort Erie and Buffalo the same year. The Canada Southern would ultimately come under the control of Cornelius Vanderbilt of the New York Central Railroad in 1875.

The Great Western system was generally single-track up to this point, having several sidings at regular intervals to allow trains to pass each other. However, especially in an age before computer or radio technology, this very much limited how frequently trains could run without risking collisions. When it was found that cross-border traffic near Windsor was reaching critical mass, the 51-mile stretch from Windsor to Glencoe was double-tracked in 1874. This was the first instance of a double-track railway in Canada. On August 7th, 1876, the Great Western began operating a new train called the “Globe Flyer” specifically for the delivery of the Toronto-based Globe newspaper. The train consisted of a 4-4-0 locomotive and a single passenger-baggage combine car adorned with advertisements for the Globe.

Competition from surrounding railways was quickly becoming untenable. The Great Western and Grand Trunk entered a race to the bottom by continuously undercutting each other’s rates. However, rail traffic on the Great Western significantly improved after 1877 with the end of a period of stagnation which kicked off with the Panic of 1873. As economic conditions improved, the Great Western entered an agreement with the Canada Southern Railway in 1878 on through traffic between Niagara Falls and Windsor which was in the best interest of both companies. The Canadian Pacific Railway was a relatively new player in Canada’s railway industry, but one with clear intentions to compete with the established railroads like the Grand Trunk and having the monetary support to do so. Now that the Great Western had become a relatively profitable entity, it had already begun discussing traffic exchange with Canadian Pacific. Desperate to keep it from gaining a foothold in the region, the Grand Trunk’s president Sir Henry Tyler began efforts to gain control of the Great Western as fast as possible. However, outright purchase or amalgamation would come with steep drawbacks. Instead, Tyler’s approach was one of influencing the Great Western’s shareholders over time and using them as proxies to influence decisions in the Grand Trunk’s favour. After offering to lease the Great Western in perpetuity one last time, only to be met with rejection from that company’s president Colonel Francis Grey, the shareholders demanded negotiations on this proposal be held between the Great Western and Grand Trunk during the Great Western’s April 1882 meeting. The heated discussions resulted in the resignation of the entire board, and an interim board was appointed instead to open negotiations with the Grand Trunk. They voted overwhelmingly in favour of amalgamating with the Grand Trunk, and effective August 12th, 1882, the Great Western ceased to exist as a corporate entity.

The Great Western Railway Today

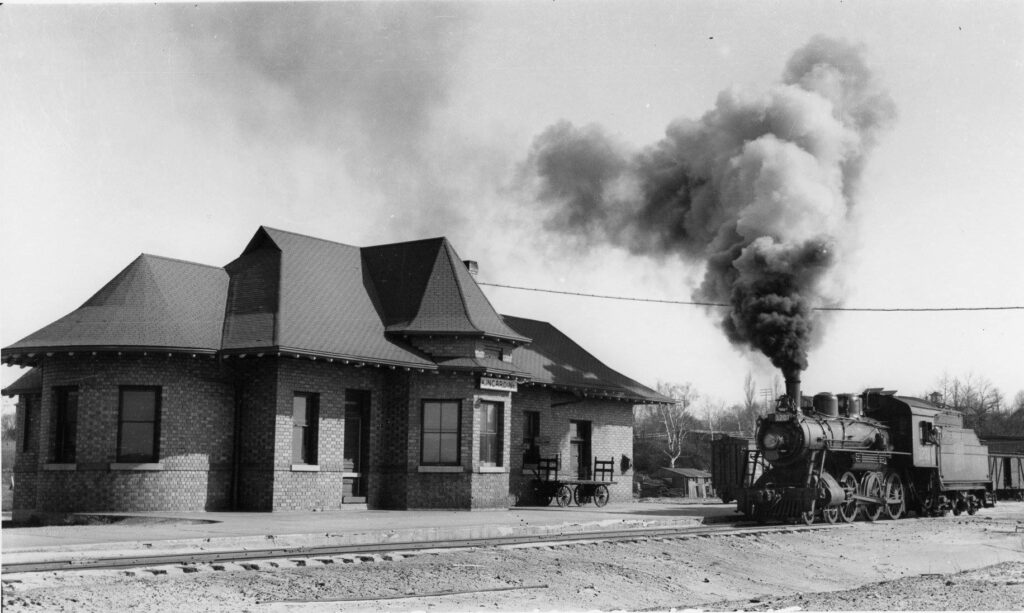

The hostile takeover of the Great Western was referred to by some Toronto newspapers as the “Railway Fusion”, and residents of Toronto were broadly against it due to reduced competition and the Grand Trunk’s past meddling in local politics among other reasons. The Great Western station at Yonge Street in Toronto was closed on August 28th, 1882, and it was used by the Grand Trunk as a bonded freight depot until 1896. It had a second life as the Toronto Wholesale Fruit Market until the structure fell victim to a devastating fire on May 17th, 1952. Even though the Great Western ceased to exist in 1882, its entire system was broadly referred to as the Grand Trunk’s Great Western Division on timetables into the 20th century. Much of the Great Western mainline remains a busy freight and passenger corridor today, and the Toronto Branch right-of-way is now the single busiest railway line in Canada. Joseph Hobson, one of the Great Western’s architects responsible for designing many of its railway stations, went on to work for the Grand Trunk after the amalgamation. He designed several stations on the Great Western Division which looked very similar to the ones he built for the Great Western Railway, such as in Windsor, Sarnia, and Woodstock. Some stations which date back to the Great Western era can still be found today though, such as in Niagara Falls and Grimsby. The latter of those is perhaps the only Great Western station to survive from the opening of the railway between Hamilton and Niagara Falls in 1853, and easily among the oldest surviving railway stations in Canada.

Sources:

Baskerville, Peter A. 2006. “Great Western Railway.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/great-western-railway.

Spriggs, W. M. 1940. Great Western Railway of Canada. N.p.: Railway & Locomotive Historical Society.

Corley, Raymond F., and Omer Lavallée. 1982. The Grand Trunk Railway: A Look at the Principal Components. N.p.: Railway & Locomotive Historical Society.

Guelph Evening Mercury. 1873. “Great Western Double Track.” May 31, 1873. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00211_18730531/4.

The Ingersoll Chronicle. 1855. “Opening of the Great Railway Suspension Bridge at Niagara Falls.” May 4, 1855. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00291_185408/148.

The Globe. 1855. “Opening of the Hamilton and Toronto Branch!” December 4, 1855.

The Globe. 1857. “Great Western Railroad Accident.” March 27, 1857.

Logan, R. S. 1912. “Synoptical History of the Grand Trunk System of Railways.” 33. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.97056/19.

Written by Adam Peltenburg