Canadian National’s First Mainline Diesel Locomotives

Less than a decade after the Prussian State Railways took delivery of the first diesel locomotive ever made, the Canadian National Railways was formed by the federal government in 1919 to consolidate the railway companies it controlled under a single entity. Shortly after its formation, Canadian National became a very early adopter of diesel technology and the first in North America to apply it in mainline passenger and freight operations. Just before the Great Depression put Canadian National’s adoption of new diesel engines on pause, a pair of diesel locomotives rolled off the floor of the Canadian Locomotive Company in Kingston, Ontario. Technically separate units when they were first built, these engines spent much of their early career sharing the road number 9000 and were fused together for a time before being split apart again. While these were not the first locomotives on Canadian National’s roster to make use of diesel fuel, they were the first that could be considered direct ancestors of today’s modern mainline diesel locomotives. Where Canadian National’s very first diesels were self-propelled passenger cars for use on light branch lines, the 9000 was its first bonafide mainline diesel locomotive. Particularly relevant to the scope of this website, is that it was also the first locomotive of its kind to ever pull a train into Toronto! However, these achievements would only be the beginning of CN 9000’s particularly eventful history.

Canadian National’s Adoption of Diesel

Canadian National was a very new railway when it first began experimenting with diesel technology. Burdened with the task of rationalizing the gargantuan Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk systems into a single network, the fledgling crown corporation was also preoccupied with retiring obsolete equipment and simultaneously procuring new rolling stock to keep up with the times. A 1924 visit to William Beardmore & Company – an engineering and shipbuilding conglomerate in Glasgow, Scotland – would motivate CNR Chief of Motive Power Charles E. Brooks and a gaggle of other railway officials to pursue diesel technology on home rails. Brooks quickly became the driving force behind the use of diesel engines on Canadian National, and A. E. L. Chorlton of the Beardmore company would directly compliment his “ability and energy” at the Engineering Institute of Canada’s Ottawa branch a year later. Their efforts would come to fruition in 1925 upon the delivery of four self-propelled passenger cars manufactured by the Ottawa Car Company. All were fitted with Beardmore diesel engines but were designated as “oil-electrics” in virtually all promotional material. They were intended to run independently or hooked up with additional passenger cars when necessary. Starting on November 1st, 1925, one of these self-propelled cars would go on to set four world records on a 67-hour journey from Montreal to Vancouver. Having never turned its engine off during the entire trip, both the public and railway officials alike were impressed with its performance. A more powerful oil-electric car made its way from Montreal to Toronto two years later. By 1928, one of these oil-electric cars was already being used regularly between Hamilton, Toronto and London.

In spite of the numerous benefits that came with diesel locomotives, the technology that existed at the time could only be applied in limited contexts. The tractive effort of most diesels was superior to steam locomotives at slow speeds. However, the opposite was the case when higher speeds were reached. As a result, most diesel locomotives that existed at that time were designed for switching moves in rail yards and industries. Trains on branch lines also often operated at low speeds due to track condition among other factors, so the oil-electric cars were well suited to them. Branch line passenger service was among some of the least profitable for Canadian National due to low ridership and the naturally high operating costs of conventional steam-powered passenger trains.

However, Canadian National and its chief of motive power were not about to let these limitations stop them from pushing the technology forward. Charles Brooks wrote an article for Railway Age in the June 9th, 1928 issue in which he highlighted the successes of the oil-electric cars. In the last paragraph, he announced his company’s plans to take delivery of their first diesel locomotive intended for high speed mainline service. Such an engine would need to be especially powerful, and Brooks explicitly pointed out that this new locomotive would be capable of 2,500 horsepower – significantly more than any of the oil-electric cars. By this point the production of the new locomotive was well underway, and it would make its first appearance on the high iron later the same year.

Birth of the Mainline Diesel Locomotive

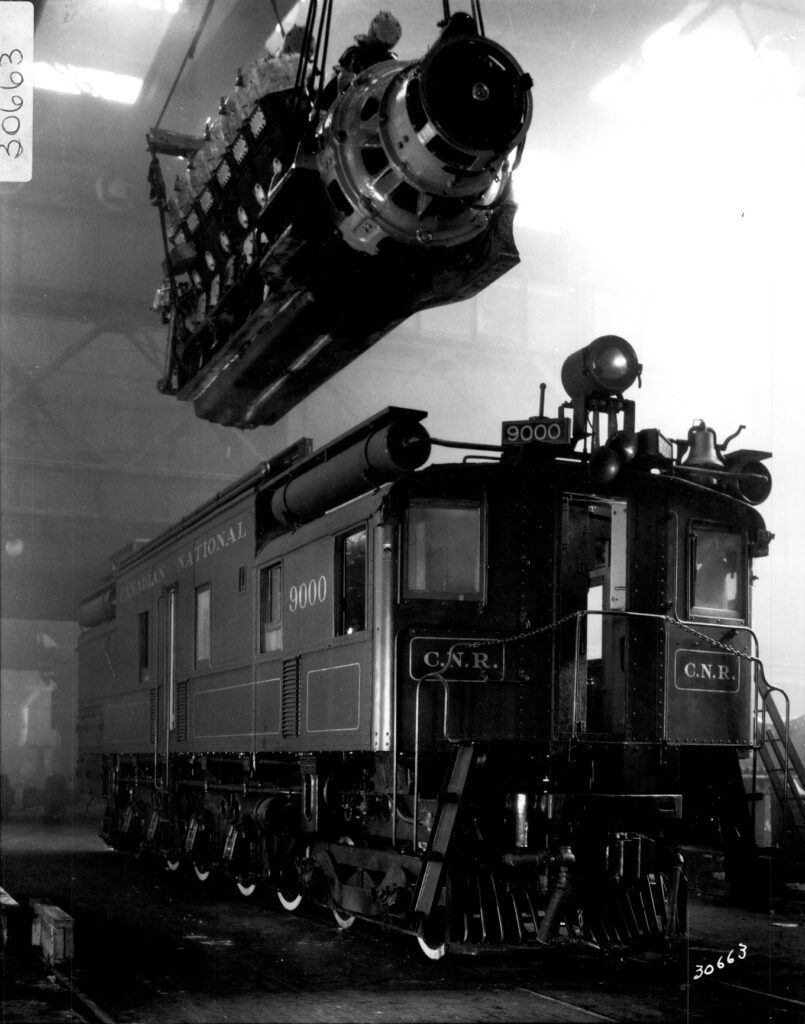

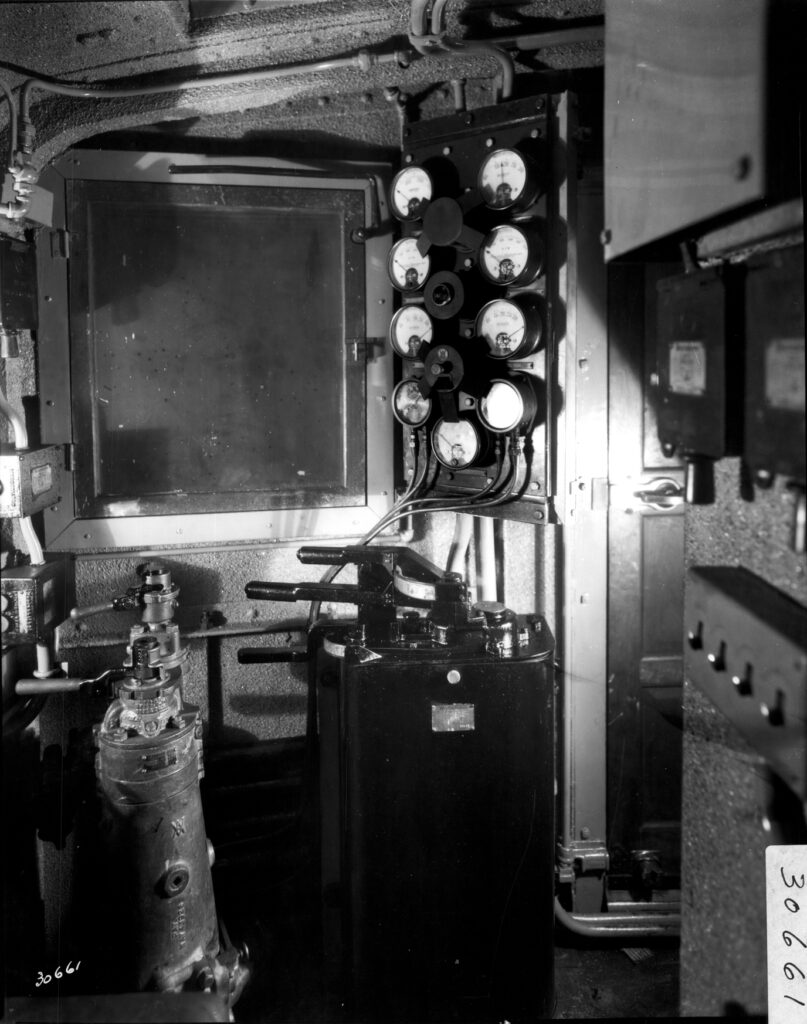

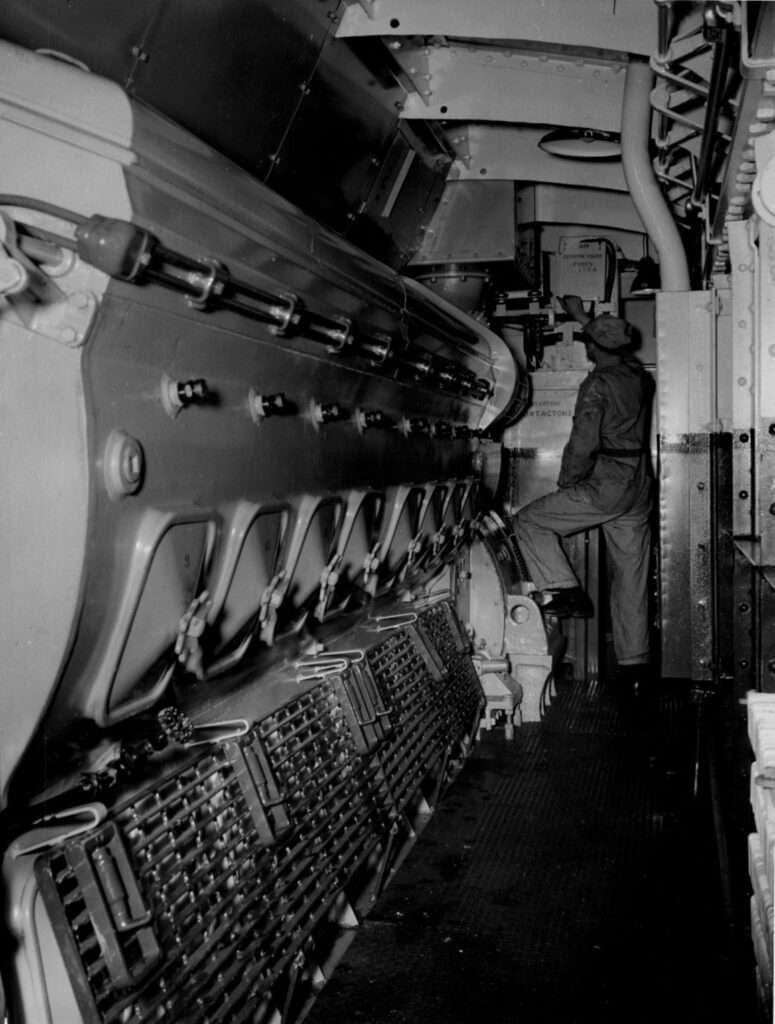

The manufacture of Canadian National’s first mainline diesel engine was a joint venture between numerous Canadian, American, and European companies. The Baldwin Locomotive Works and Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing – both based in the US state of Pennsylvania – worked alongside Canadian National itself to come up with the design. Westinghouse was also responsible for manufacturing the locomotive’s electrical equipment. The Commonwealth Steel Company of Granite City, Illinois produced the underframes. Just as had been the case with Canadian National’s self-propelled diesel cars, each of the new diesel units were supplied with a 1,330-horsepower V12 diesel engine by the William Beardmore Company of Scotland. The carbodies were manufactured domestically by the Canadian Locomotive Company in Kingston, Ontario, which is also where the locomotives were finally assembled. The locomotives were painted to match Canadian National’s steam fleet at the time – all black with gold lettering and numbers. Under its own alphanumeric locomotive classification system, Canadian National designated both units as V-1-a. The first of the two units, numbered 9000, rolled off the factory floor and was delivered to Canadian National on November 20th, 1928.

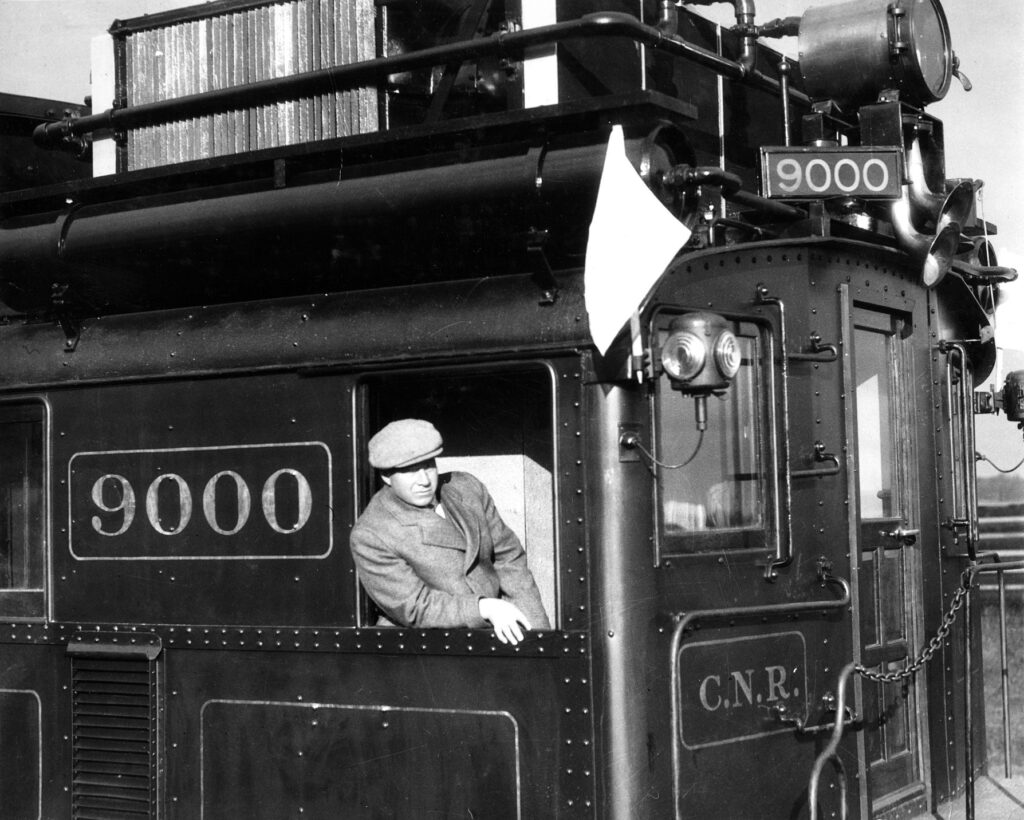

On that same day a group of railway executives, employees and other important figures arrived in Kingston to take the new locomotive for a spin. The inaugural train consisted of 9000 plus two passenger cars and a caboose. The first passenger car contained a dynamometer to take measurements, while the second was a business car for the executives to ride in. Invited guests on the trip included William Casey and J. C. Wilson, executives of the Canadian Locomotive Company and the Canadian subsidiary of Westinghouse, respectively. Engineer Herbert J. Palmer was selected to pilot 9000 on its inaugural run, for which he was given special training ahead of time. The locomotive ran well, though it wasn’t without its teething problems. Since steam was so readily available at the time, virtually all passenger cars were designed to be heated with steam piped directly from the locomotive in colder weather. Lacking a pre-existing source of steam, 9000 was given its own steam heating system to emulate the same process – a common design feature on many early diesels. Unfortunately, it operated sporadically due to vibrations from the engine. A problem was also encountered in which the air brakes would go into an emergency application approximately every 20 miles. A blueprint from Westinghouse had to be used part way through the trip to locate the problem. While the trial run was originally supposed to terminate in Brockville, it ended up running a further 125 miles to Montreal. The train had kept to a maximum speed of 25 miles per hour up to this point, but by Cornwall it was able to achieve an impressive 65 miles per hour. After arrival in Montreal, the locomotive was taken to the Montreal Locomotive Works to correct an issue with the journal bearings.

The following day, another test run was made from Montreal to Ottawa. This time 9000 was to pull a coach and six business cars. Among the executives on board was Sir Henry Thornton, who was Canadian National’s president at the time. Minister of Railways S. J. Hungerford was also in attendance. The goal was to beat the existing schedule between those two cities by ten minutes. The locomotive did so well that the engineer had to apply the brakes on at least one occasion to avoid arriving early. After arriving in Ottawa the group of executives went to inspect the locomotive. No doubt an enjoyable experience for all, at least until Henry Thornton slightly injured himself by hitting his head on a signal box bracket inside the engine.

Next, Canadian National sought to test 9000’s ability to pull a typical mainline freight train. A cut of 57 freight cars was brought from Turcot Yard in Montreal along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario. The train eventually made it to Port Union, where a helper locomotive was normally required to couple to the front and assist conventional trains over the hill at Scarborough. In the case of 9000, a helper locomotive was sent ahead of the train and would only be used if the train stalled. No such help was needed and 9000 continued to pull the train over the summit at Scarborough and down the Danforth Hill into Toronto. While this was the locomotive’s first time in the city it seems the occasion went largely unnoticed, except by passersby who would have briefly seen the train making its way through the Union Station Rail Corridor. The train proceeded through Hamilton and ended its run in Fort Erie. On the return trip to Mimico, the locomotive was reportedly coupled to a “heavy coal train” with an unspecified number of cars. It was routed onto the now-abandoned railway line along Burlington Beach where a steep grade was encountered when entering Burlington from the south. When the engineer increased the throttle to build up momentum on the approach to the hill, a knuckle broke which required a brief stop on the hill. Miraculously, the engine was able to continue on its way with little trouble. The 9000 was uncoupled from the train in Mimico and paired with an assist engine, and both were then brought to the Spadina Roundhouse in Toronto.

A Short-Lived Golden Era

The second diesel locomotive was given to Canadian National in April of 1929, and the two were joined together a month later. Despite technically being two distinct locomotives, they were treated as a single locomotive from this point forward and the new one was given the same road number as its twin. By the end of summer, officials of Canadian National found the perfect way to premiere the country’s first mainline passenger diesels to the public. The International Limited was Canadian National’s express passenger train between Montreal and Chicago. Its consist was typical for many of CN’s high priority passenger trains at the time and it was most often powered by 4-8-2 Mountain-type steam locomotives, which is precisely what CN 9000 was intended to compete with. This train represented what mainline diesel locomotives would be required to pull in regular service, so it made for the perfect test bed. On August 26th, 1929, two instances of the International Limited departed Montreal on the same day. The first used a conventional steam locomotive and departed at its regular time, bound for Chicago. The second, pulled by CN 9000, left 30 minutes later at 10:00 am. The train consisted of a combination baggage and smoking car, a day coach, three club-observation solarium cars, and two business cars. As was the case with the many trials before this run, numerous important figures were on board. Representatives from all the companies involved in CN 9000’s construction and municipal politicians from towns along the International Limited’s route were present. The event drew reporters from both Canada and the United States.

The train led by CN 9000 made thirteen intermediate stops on its way to Toronto, just as the real International Limited would have. The train left up to a few minutes late at some of the stops but had little trouble making up that time, owing to the engine’s tractive effort at low speeds allowing it to accelerate quickly. It was estimated that 9000 could accelerate twice as fast as a comparable steam locomotive, even while pulling all 663 tons of the 7-car passenger train behind it. 9000 reached speeds of 60 to 65 miles per hour with ease during this trip, even reportedly reaching a speed of 73 miles per hour for a short period of time. It made quick work of the scheduled 7 hour and 40 minute journey of the International Limited, arriving in Toronto Union Station at 5:40 pm. Locomotive 9000 was then used to pull the train to the railway display track at Exhibition Place for 6:10 pm, where members of the public and numerous press photographers could see the engine up close. This run was perhaps the most famous in 9000’s operating history, receiving a significant amount of national and international attention. While many in the railroad industry were still unconvinced that diesel engines would eventually replace steam, the fate of steam power in Canada was most definitely sealed.

The New York Stock Exchange experienced a crash just two months later on October 29th, 1929, an event known as Black Tuesday which many historians associate with the start of the Great Depression. Possibly as a result of the increasingly difficult economic times, CN 9000 seemingly disappeared from the public eye in the three years after it was put in charge of the International Limited. However, something interesting happened as the depression worsened into the early 1930’s. The conjoined units that made up CN 9000 were split apart and the second unit was given the number 9001 to differentiate. Starting in 1931, the two were used to pull several local passenger trains out of Toronto Union Station. While this assignment would have made the pair of diesels a regular sight in downtown Toronto and parts of southern Ontario for nearly a decade, very little of this activity was recorded. The few photographs that exist show them on trains heading east towards Oshawa or west towards Hamilton. The units were likely based out of the Spadina Roundhouse where Canadian National’s passenger equipment was stored and maintained.

The depression effectively ceased the development of a variety of new technologies Canadian National had been experimenting with during the Roaring Twenties, with diesel being one of them. Contributing significantly to the pause on diesel was the loss of its main promoter, Charles E. Brooks, who passed away in 1933. CN 9000 and 9001 continued to operate in both Ontario and Quebec to some extent until October 17th, 1939, when both units were retired and put in storage.

CN 9000 Goes to War

Under ordinary circumstances this is the point in which CN’s first pair of road diesels would either be scrapped or, in especially rare cases during this period, preserved. There is nothing ordinary about what comes next, however. A resurgence of war in Europe prompted Canada to join its allies on September 10th, 1939. Two years later, Canada officially declared war on Japan on December 7th, 1941, immediately following their attack on Pearl Harbour. The latter event motivated a strengthening of defences on Canada’s west coast in the event of a Japanese attack. The concerns surrounding this threat only grew when Japanese forces landed on parts of the Aleutian Islands in Alaska on June 6th and 7th, 1942. This development made the port of Prince Rupert, British Columbia very important for the shipment of supplies to American forces in Alaska. As such, Prince Rupert was now a prime target for Japanese raids. In cooperation with the American military, the Canadian forces fortified the town and its port. However, the sole railway line connecting Prince Rupert to the rest of Canada was still vulnerable to sabotage. All 150 kilometres of the former Grand Trunk Pacific line between Prince Rupert and Terrace ran through isolated wilderness that was easily accessible from the nearby Skeena River. The Canadian military’s solution to this vulnerability was an armoured train – the only such instance of one in Canada.

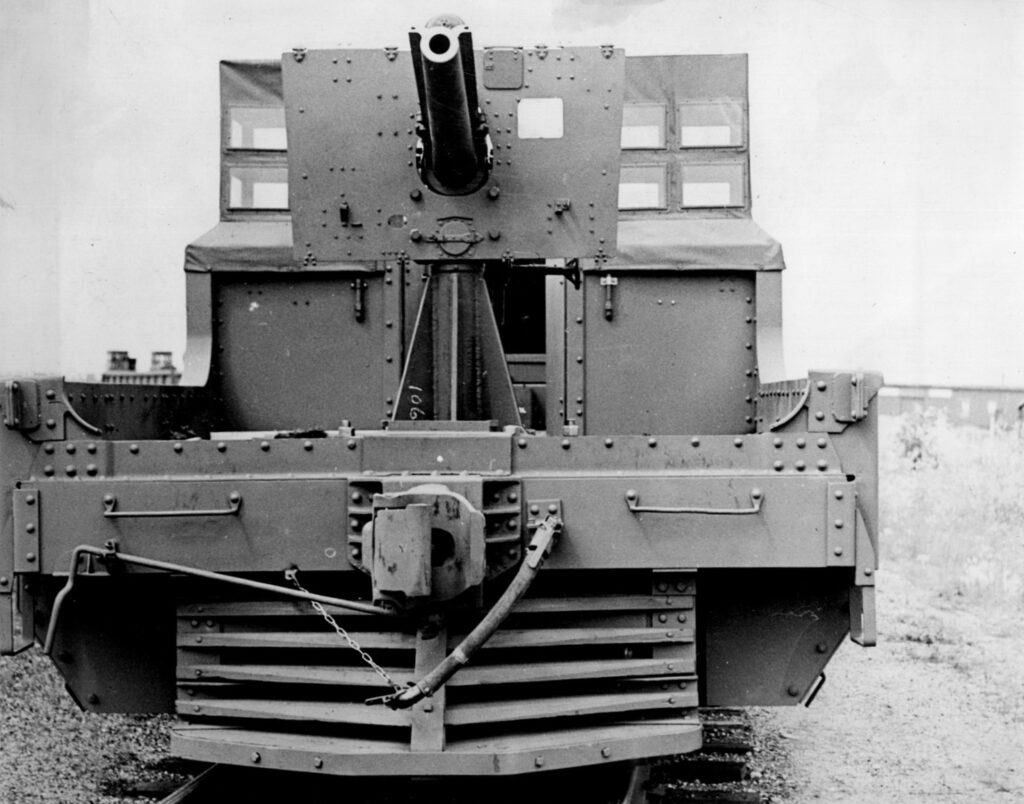

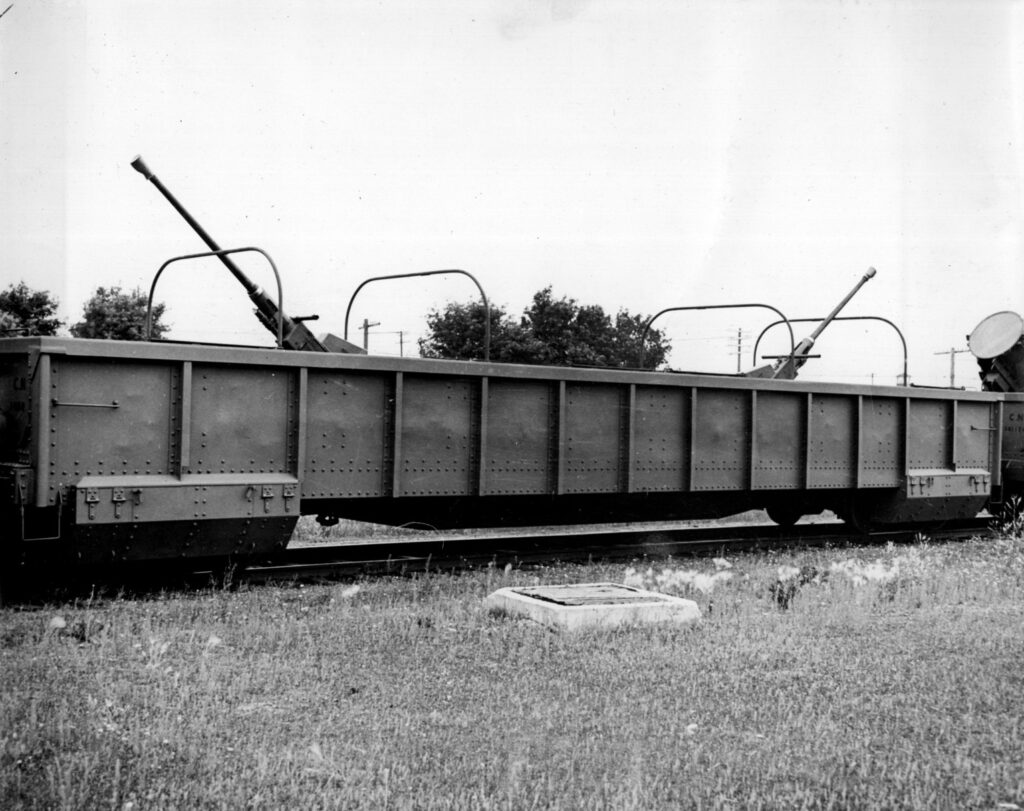

CN 9000, having now spent three years in storage, was ultimately chosen by the military to provide power for the armoured train. The necessary modifications to the locomotive were completed by Canadian National’s Transcona Shops in Winnipeg on July 15th, 1942. Part of this work involved the replacement of the 1,330-horsepower Beardmore engine with a newer 1,350-horsepower engine from General Motors. The locomotive’s exterior was given so much armour that it was rendered practically unrecognizable from its original form. This was an intentional design choice to have it resemble a plain boxcar from the air. The rest of the equipment used on the armoured train was already produced over the previous month. In addition to armour, the train was designed to carry a significant amount of firepower. The primary armament was a 75mm artillery gun positioned at both ends of the train. Multiple flatcars were equipped with searchlights and pairs of 40mm Bofors autocannons to provide air defence. Several modified boxcars were used to carry military personnel and equipment, including a headquarters car containing a radio, medical inspection room, and a kitchen. The train was designed to be a “home away from home” for a Royal Canadian Artillery gun crew and an infantry rifle company in addition to command, signaling and medical personnel. A civilian crew employed by Canadian National would be assigned to pilot locomotive 9000, which was positioned in the middle of the consist with a roughly equal number of cars on both sides.

The armoured train was delivered to the Canadian forces in Terrace, British Columbia in parts between July and August of 1942, and it was rushed into service soon afterward. It was originally scheduled to patrol the tracks between Terrace and Prince Rupert twice in each direction per day. However, in the hurry to get the train operational it was missing the headlights required to run at night and the second trip couldn’t be made. The schedule, missing equipment and other concerns were gradually sorted out over the next several months. CN 9001, which was originally slated to become a spare locomotive for the armoured train, ended up cannibalized for parts to keep 9000 operational. The train’s relevance was significantly diminished with the American forces’ retaking of the Aleutian Islands in August 1943. CN 9000 made its final run in a military capacity on September 17th, 1943. The train was kept in Terrace for a short time afterwards in case it was needed, but no new threats arose. Most of the armour was removed from locomotive 9000 in November of 1943 and it was subsequently returned to Canadian National.

The armoured train’s existence was largely kept a secret until after the war ended. Its history was described in detail in an article titled No. 1 Armoured Train by Major Louis E. Grimshaw and published in the October 1991 issue of Canadian Defence Quarterly. That article was reprinted in the September 1992 issue of Branchline, a magazine directed towards railway enthusiasts.

The Abrupt End of CN 9000

Canadian National proceeded to use 9000 in limited capacities through the mid-1940’s after it was found to have an inferior chassis for the operational needs of the time. Despite its limitations, it was assigned to the Montreal area in December of 1943. Contemporary sources indicate that the locomotive was used in passenger service during this assignment, but on at least one occasion it was photographed pulling a freight train. In January 1945, just several months before VE Day, the remainder of the armour was removed from 9000 and it was reassigned to passenger service between Quebec City and Edmundston, New Brunswick. There was much internal discussion as to the best way to find use for CN 9000 during this time. These considerations also involved CN 9001 which was still in the picture albeit in storage. The options for the two pioneer diesel locomotives ranged from hump yard switching to electrification, either for the Deux-Montagnes Line in Montreal or the St. Clair Tunnel in Sarnia.

However, there was a complication that would prevent any such modifications from happening. Canadian National was not yet the rightful owner of the GM engine placed inside 9000 during the war. It still belonged to the Department of Munitions and Supply who originally purchased it. CN finally bought the engine from the department for $10,000 in 1947, but by then it was too late. Both units were officially re-retired in October 1946 and they were scrapped before the negotiations had finished. The railway preservation movement was then in its fledgling stages, its earliest organizations such as the Canadian Railway Historical Association or the Upper Canada Railway Society had only been founded within the previous ten years. As such, it would take decades for these organizations to build up the necessary credibility for preservation to be considered when historic railway equipment was on the chopping block. An article in the January 1965 issue of Canadian Rail, a publication issued by the CRHA, would directly lament the loss of 9000 two decades earlier. As the author of that piece states in the fourth paragraph, “How we would go after the CN’s original 9000 now if it were being retired next month!!!”.

Despite the 9000 and its twin disappearing from Canadian National’s roster over a decade before diesel supplanted steam in revenue service, it seems it had a certain degree of cultural staying power particularly among railway enthusiasts and history buffs. In addition to numerous articles written about it over the years, the 9000 would appear on a stamp issued by Canada Post in 1986. It was part of a series of stamps themed around Canadian locomotives of the early 20th Century, and the 9000 was shown in its 1929 configuration when both units were joined together. In 1948, Canadian National would take delivery of its first new mainline diesels since 1929. Either through pure coincidence or possibly as an intentional nod to its predecessor, the first locomotive in this series was numbered 9000.

Written by Adam Peltenburg

References

“Oil-Electric Cars, Canadian National Railways” 1926. Canadian Railway and Marine World, (January).

Brooks, Charles E., 1928. “Oil-electric motive power on Canadian National.” Railway Age 84, no. 23 (June).

“Canadian National Demonstrates High-Power Oil Locomotive.” 1929. Railway Age 87, no. 10 (September).

“Our Cover.” 1965. Canadian Rail, 162 (January).

MacKay, Donald. 1986. The Asian dream : the Pacific Rim and Canada’s national railway. N.p.: Douglas & McIntyre.Grimshaw, Louis E, 1992. “No. 1 Armoured Train”. Branchline 31, no. 8

Grimshaw, Louis E., 1992. “No. 1 Armoured Train”. Branchline 31, no. 8

Kennedy, Raymond L. n.d. “Early Diesels.” Old Time Trains. Accessed December 5, 2022. http://www.trainweb.org/oldtimetrains/Various/early_diesels.htm.

Special thanks to Eric Gagnon for assistance in identifying the date of 9000’s first run