Introduction

From the commencement of construction in 1874 until its takeover by the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1884, the Credit Valley Railway Company only existed for a single decade. It was among a half dozen railways that operated in Toronto during the first 30 years of the railway era. Yet, more than the others, the name of the Credit Valley Railway (CVR) lives on today in public consciousness. In the 1970s, the name Credit Valley was revived as part of an ambitious plan to operate steam locomotive-hauled excursions in southern Ontario. In the 21st century a 37-kilometre section of the CVR survives as a popular tourist train operation and in the name of one of the Greater Toronto Area’s busiest model railway shops. The published literature on CVR is considerably sparse. Other than a slim monograph published in 1974, there have been no books devoted to this important, although short-lived, railway. Perhaps the primary reason for this literary drought is a lack of photographic documentation, with only a handful of known images showing the CVR in operation prior to its absorption into the CPR in 1884. Despite this limitation, the CVR was one of the most important acquisitions by Canadian Pacific during the period in which it was building its transcontinental railway. Today the former CVR right of way west of Toronto remains a critical link between Eastern Canada and the Midwestern United States. This route also carries GO Transit’s Milton service, one of its busiest commuter rail lines.

Building the Credit Valley Railway

The railway era was relatively late coming to Canada West, as Southern Ontario was known prior to Confederation. The first steam powered passenger train had begun operating in Great Britain in 1825 and in the United States in 1830. By 1850, there were 9,000 miles of track in the U.S. and less than 60 in Canada, all of it in Quebec. The first revenue train departed from Toronto in May 1853. The initial phase of railway construction in the 1850s resulted in three railways out of Toronto: the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron (renamed Northern Railway of Canada in 1858), Grand Trunk and Great Western. These were all built to the broad gauge of 5’6” that was mandated by the colonial government. Following this initial flurry of railway building, an economic depression in 1857 ended any further expansion until the 1870s. The CVR was incorporated in 1871 to build between Toronto and Orangeville by way of Streetsville and the Credit River Valley, the geographical feature that gave the railway its name. After the government abolished the broad gauge requirement in 1870, two new railways, the Toronto & Nipissing and the Toronto, Grey & Bruce were built to the narrow gauge of 3’6” and the CVR made initial plans to build to this gauge as well. However, by the time construction began on CVR in 1874, the narrow gauge phase was over and it was built to the standard 4’8½” gauge.

The promoter behind all three of these new railways was George Laidlaw, a Scottish-born Torontonian who had immigrated to Canada in 1855. Laidlaw was known as the “Prince of the Bonus Hunters,” a moniker based on his ability to find government agencies and municipalities willing to subsidize new railway construction. These investors were often towns that had been bypassed during the initial phase of railway construction in the 1850s and now found themselves at an economic disadvantage without a rail link. Another important motivation for these municipal subsidies was to break the near monopoly that Grand Trunk had enjoyed in southern Ontario for almost two decades. In Toronto particularly, GTR was despised for its high-handed manipulation of local politicians and its absentee British management unwilling to respond to local priorities. Laidlaw was able to raise $1,165,000 for his Credit Valley project from various municipalities, including $350,000 from the City of Toronto, the equivalent of $6 million today. Beyond his promotional efforts, Laidlaw was not involved with the actual construction nor the operations of Toronto & Nipissing and Toronto, Grey & Bruce railways that essentially only serviced the hinterlands of Toronto. It was soon apparent that Laidlaw had far more ambitious plans for his new Credit Valley Railway.

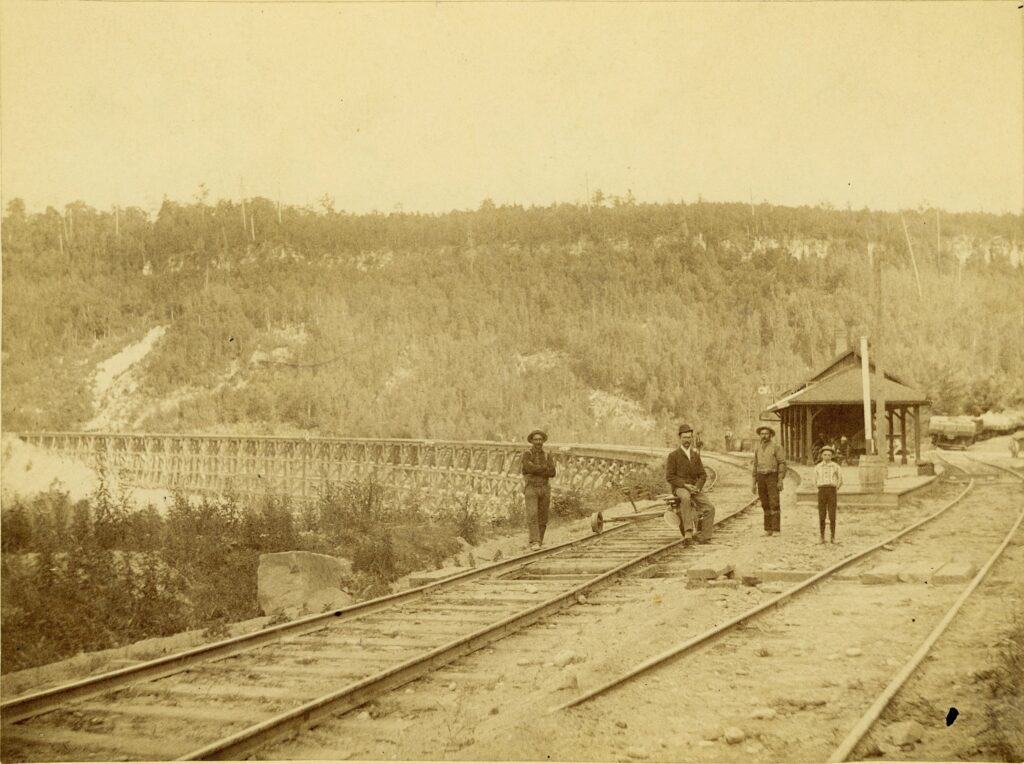

While CVR would build branch lines from Streetsville to Orangeville and Elora, the main line was to extend all the way to St. Thomas, 111 miles west of Toronto, where it would connect with Canada Southern Railway, providing access to Detroit, Chicago and the American Midwest. Thus did CVR become known as the “Third Giant,” ranking after the Grand Trunk and Great Western railways that also provided connections from Toronto to the vast and lucrative American markets. Laidlaw not only promoted and built Credit Valley, he served as the railway’s president. Among the most formidable engineering challenges facing CVR was the bridge over the Humber River at Lambton, three miles north of the river’s mouth at Lake Ontario. This was a timber bridge supported on stone piers and was described by the Woodstock Sentinel in 1874: “The spans are built on the ‘Howe’ truss principle; one of 115 feet, one of 138 feet and three of 105 feet each, making a distance of 568 feet of truss at a height of 95 feet above the river. There are 800,000 feet of timber, almost 118,000 pounds of iron on the bridge and 3,186 yards of solid masonry in the piers supporting the span.”

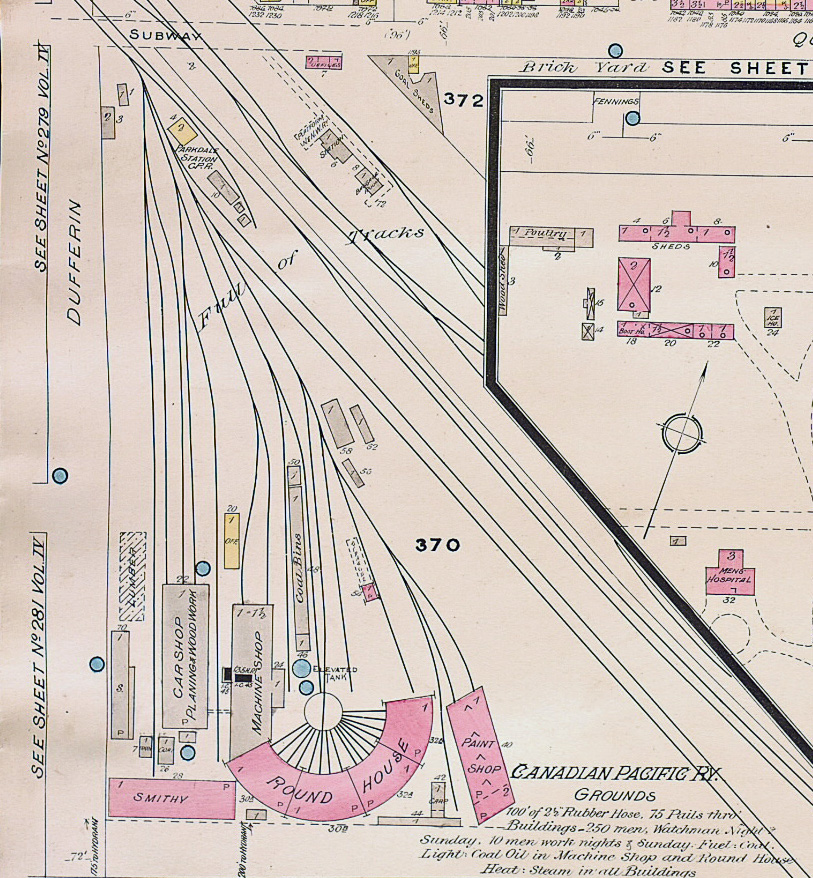

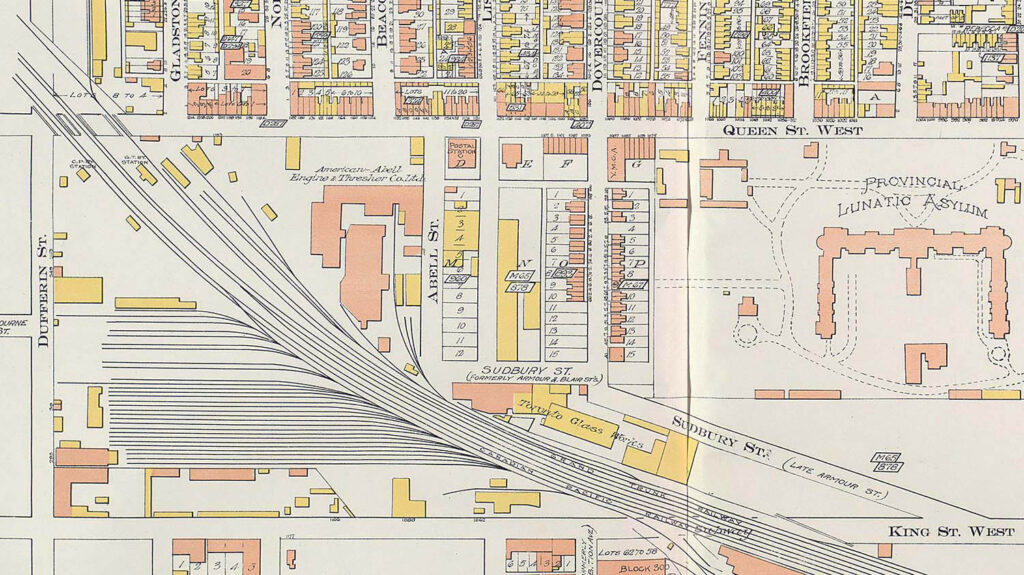

Unlike Grand Trunk, whose construction of the huge bridge over the Ganaraska River in Port Hope had delayed the opening of the Montreal-Toronto line for several months in 1856, CVR’s Humber River bridge was completed in 1874, years before revenue trains began operating over it. An even greater challenge for the railway, although more from a legal rather than an engineering perspective, was access to Toronto. CVR entered the city along the northwest rail corridor through Parkdale that had already been established by the Northern, Grand Trunk and Toronto, Grey & Bruce railways. In 1878, CVR purchased from the provincial government ten acres of property on the west edge of the city, northeast of King and Dufferin streets, where it built a four-stall engine shed and turntable. Although the municipality of Parkdale was actually west of Dufferin Street, the railway facilities located on the east side of the thoroughfare were known by that name and became CVR’s principal Toronto terminal for locomotive and car maintenance. In June 1879 the railway solicited bids for the erection of blacksmith and machine shops on the site. The problem at Parkdale was that the Northern Railway had spitefully built a new passenger station south of Queen Street that effectively blocked Credit Valley’s entrance into the city. The CVR was able to build a right-of-way on the western side of this corridor, but this required complicated switching moves in order for trains to reach its terminal facilities and passenger station at Parkdale and the railway had no access at all to downtown Toronto and Union Station. This awkward arrangement would have fatal consequences for Credit Valley.

On May 10, 1879, a CVR inspection train was touring the line and carried a private car filled with investors and officials, including president George Laidlaw. South of Queen Street, the train pulled into a siding to wait for a Grand Trunk locomotive that would haul the train into Union Station. When a GTR engine approached, the crew of the CVR switcher assumed it was coming to pick up the car and aligned the switch into the siding, not realizing that this locomotive had no intentions of slowing down but was actually heading farther up the line. The engineer was not able to stop the locomotive in time and it plowed into the car, seriously injuring several prominent Toronto businessmen and propelling CVR investor and board member James Gooderham out onto a pile of ties. His injuries were fatal and he died the next day.

The Commencement of Operations

Credit Valley Railway was under construction for six years before regular passenger train service began in Toronto in 1879. This was not the first section of the CVR to open as it had begun service between Woodstock and Ingersoll in September 1878. Some contemporary published accounts have erroneously reported that the line opened between Parkdale and Milton in 1877. In November 1878, track laying of the 55-pound rail was still in progress at Lambton Mills, where Dundas Street crossed the Humber River, and was proceeding westward at the rate of about a mile per day. On November 9, 1878, the first revenue freight was delivered by Credit Valley in Toronto, a stationery engine for the firm of P. & F.A. Howland, a flour mill located along the Humber River. Many years later, the ruins of this structure would be incorporated into the popular Old Mill Restaurant complex. The lengthy delays in construction were primarily related to Credit Valley’s precarious financial situation. Full payment of Toronto’s construction bonus was being withheld until the tracks reached east as far as Bathurst Street. The situation was further aggravated by the loss at sea of the SS Copia. The steamship had departed from Barrow, England on September 11, 1878 with 1,700 tons of rails and fastenings for delivery to the CVR and was lost at sea. An alternative supply was located in Buffalo, but this further delayed construction by months.

The first verifiable date for a revenue CVR passenger train in Toronto was September 1, 1879. The Globe reported that the company had built a simple passenger platform at Queen Street in Parkdale and that a proper station was under construction. Two trains a day were scheduled in each direction between Campbellville and Toronto. The date coincided with the opening of the new Toronto Industrial Exhibition, which was entering its second year as an annual fair and already attracting enormous crowds from all over the province. The CVR’s Parkdale station wasn’t as conveniently located as the Great Western station located adjacent to the Exhibition entrance on Dufferin Street so CVR employed horsedrawn omnibuses that shuttled up to 600 passengers a day from Queen Street to the entrance. Once the Exhibition was over, regular passenger service between Campbellville and Toronto began on September 15, 1879.

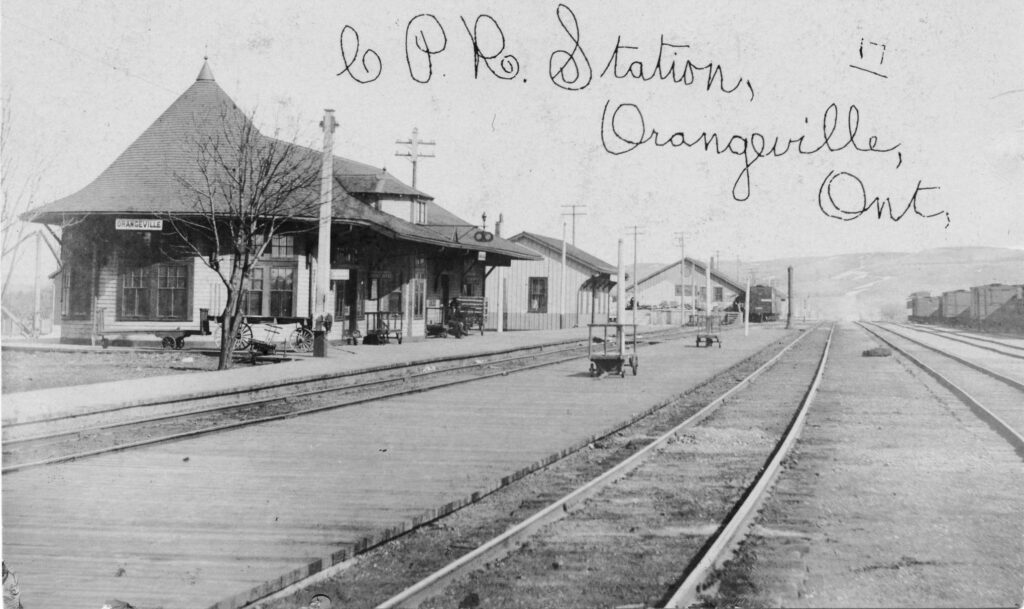

The official opening of Credit Valley Railway was held in Milton on September 19, 1879 and the guest of honour was the Governor General of Canada, the Marquis of Lorne. His Excellency’s private car brought up the rear of a five-car train that departed from Parkdale at 10 a.m. The locomotive, ‘R.W. Elliott,’ a 4-4-0 built in Kingston, decorated with flags and evergreens for the occasion, hauled the train. It was reported that the ride over the recently completed roadbed was much smoother than on some older more established railway lines. The return trip from Milton took 65 minutes and Lorne was back in Toronto by 1:30 p.m. in time for a scheduled visit to the exhibition. With CVR now active in Toronto, traffic picked up considerably. In November 1879, the railways solicited tenders for new rolling stock that included 10 coaches, 4 baggage and express cars, 4 mail and smoking cars, 200 box cars, and 150 flat cars. On December 2, 1879, CVR began passenger train service between Toronto and Orangeville with an early morning train departing Orangeville at 7 a.m. and returning at 8 p.m. The locally generated excitement that normally attended the completion of a new railway may have been muted by the fact that Toronto, Grey & Bruce had already initiated passenger service between Toronto and Orangeville in 1871. However the citizens of Orangeville were now in the enviable position of having two competing railways providing a choice of service.

The opening of the Elora Branch was delayed by two weeks since the Great Western Railway had not yet installed a necessary diamond crossing at Fergus. On December 17, 1879, regular passenger service began on the 27.5-mile Elora line that branched off from the Toronto-Orangeville mainline at Church’s Falls, later renamed Cataract. By this time there were four trains a day in each direction, to and from the Queen Street station in Parkdale. Credit Valley Railway provided Torontonians with some of the most dramatic scenery to be seen within a pleasant day’s round trip from the city. In an era long before the family automobile and when traveling long distances for recreation was a privilege only enjoyed by the rich, daytime excursions from the city by steamship or train were the mainstay of the local tourism industry. Only a two-hour ride from Toronto was the spectacular Forks of the Credit, located in the railway’s namesake valley, where the three branches of the Credit River joined together. CVR built a curved trestle 1,146 feet long and 85 feet above the river, which was surrounded by the scenic Caledon Hills. Two hundred yards from the Forks station the railway built an open recreation pavilion with seats, picnic tables, swings and a dance floor. Local newspapers were rhapsodic in their descriptions of the scenic delights available to city dwellers.

In order for the CVR to maintain its newly thriving passenger business, a more conveniently located downtown station was essential. At this point in Toronto’s commercial development, the central business district was still concentrated east of Yonge Street. Both Great Western and Northern railways had initially built passenger terminals west of Brock Street (Spadina Avenue) but had relocated them east of Yonge in the mid-1860s. In 1873, Grand Trunk Railway had built a new Union Station between Simcoe and York streets, but it wasn’t about to offer easy access to their new rival – the Credit Valley Ry. As a stopgap measure, the CVR established a downtown ticket office at 6 Wellington Street near Yonge Street where passengers could check baggage and purchase tickets. Finally, on May 17, 1880, the Credit Valley obtained access to the Grand Trunk’s Union Station, a facility that had thus far owed its “union” status to the few trains of the Toronto, Grey & Bruce that used the station. As if to provoke their new landlord, CVR scheduled a train to depart Galt a half hour after the Grand Trunk train, arriving at Union Station a half hour ahead of their rival. Once installed at Union Station, the CVR immediately reported a great upsurge in passenger traffic, however, their problems with the Grand Trunk and the other Toronto railways were far from over.

Throughout the railway era, passenger trains have furnished railway companies with considerable public relations status and glamour, but freight trains have usually provided the bulk of the profits. Credit Valley freight traffic was at a distinct disadvantage as long as downtown businesses had to haul their goods to and from Parkdale for shipment. The railway purchased water lots between John and Simcoe streets and was in the process of filling them in and building a large freight house and dock. A young entrepreneur named William Mackenzie, who had recently entered the railway contracting business, built the cribbing for this project. Mackenzie would later find fame and glory as the proprietor of the Toronto Railway Company, the municipal streetcar network, and the Canadian Northern Railway, the only transcontinental railway to have its headquarters in Toronto. The problem for CVR was connecting this waterfront property with the main line, which was critical to the company’s economic survival. No railway could prosper without direct access to the harbour and the capacity to interchange freight with the still extensive system of steamboats and sailing vessels that plied the Great Lakes. It had long been established that new railways could cross over existing lines as long as the newcomer paid for the crossing, maintained it, and provided whatever staffing and facilities were required to keep it operating safely. The situation at the Toronto waterfront was that, to reach its own property, CVR had to cross over a total of thirteen tracks owned by four competitive railway companies, none of whom were prepared to facilitate easy access to a rival. The waterfront rail corridor was already severely overcrowded with little room for new installations.

The City of Toronto, having invested a fortune in the new railway, naturally sided with CVR in this dispute. The subsequent courtroom entanglements would eventually command the attention and efforts of the Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, as well as several members of his federal cabinet. By the time the issue was resolved in CVR’s favour, the Privy Council was so fed up with the acrimony that it resolved to establish a separate arms-length Board of Railway Commissioners, although it was after the turn of the 20th century before that came to pass. On Sunday, November 18, 1880, another skirmish erupted between the Grand Trunk and the Credit Valley, which had been building additional track along the north wall of the Central Prison west of Strachan Avenue. The Grand Trunk maintained a siding that crossed over the CVR right of way and erected a barrier along this track consisting of box cars, an engine and other structures to block CVR progress. Credit Valley superintendent James Ross rallied 100 workers to dismantle the GTR barricades, which occurred without incident except for complaints from nearby citizens who objected to this strenuous and presumably noisome Sunday activity. Ross published a notice in the Globe apologizing to the citizens of Toronto for the “desecration of the Sunday” and then explained why he felt such action was necessary.

This wouldn’t be the last time that CVR ran afoul of Ontario’s blue laws that prohibited virtually any kind of productive activity on Sunday. A few days later, Credit Valley concluded an agreement with Grand Trunk that allowed its freight trains to use 2285 feet of GTR track between Bathurst Junction and Brock Street (Spadina) for a rental of $1500 per annum, and 8 cents per freight car. In February 1881, the Canadian Pacific Railway was incorporated to build between Central Canada and the Pacific coast, mostly through 3,000 miles of vast uninhabited wilderness. CPR required an eastern rail network to generate the freight and passenger traffic revenues necessary to keep the company solvent and to help pay for the building of the transcontinental railway. They built new lines where needed, but preferred to buy up existing railway companies. In March 1881, businessmen associated with Canadian Pacific revived the dormant decade-old charter of the Ontario & Quebec Railway that had been established to build a line between Ottawa and Toronto by way of Peterborough. The charter was revised to build from some point on the Canada Central Railway (by this time part of CPR) between Smiths Falls and Carleton Place, westward to a connection with the Credit Valley Railway at Toronto, “by the most direct and easiest route the physical features of the country will admit.” The revised charter was much broader in scope with ample provisions for leasing, acquiring or amalgamating with other railways, advantages that Ontario & Quebec would make full use of in the next few years.

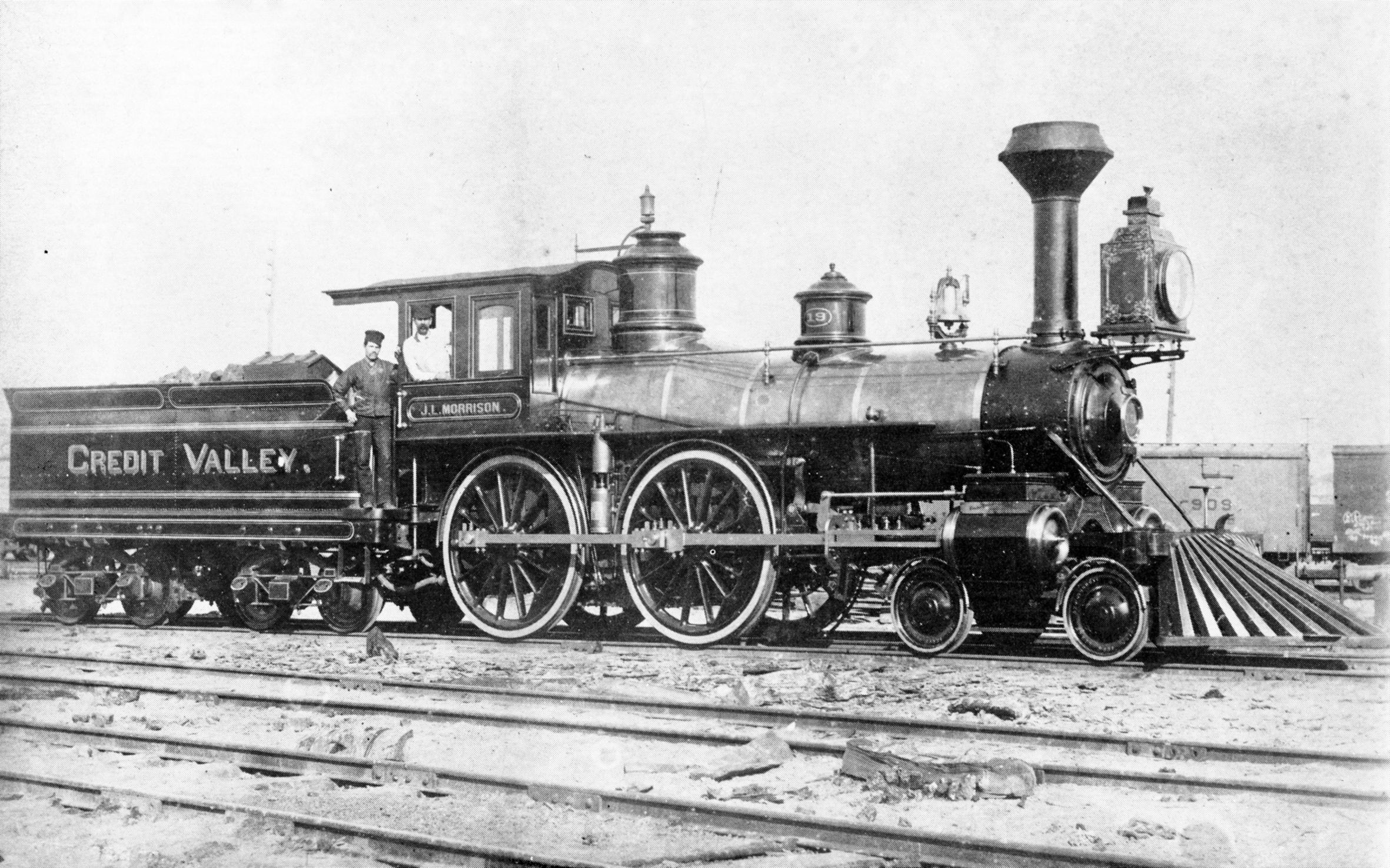

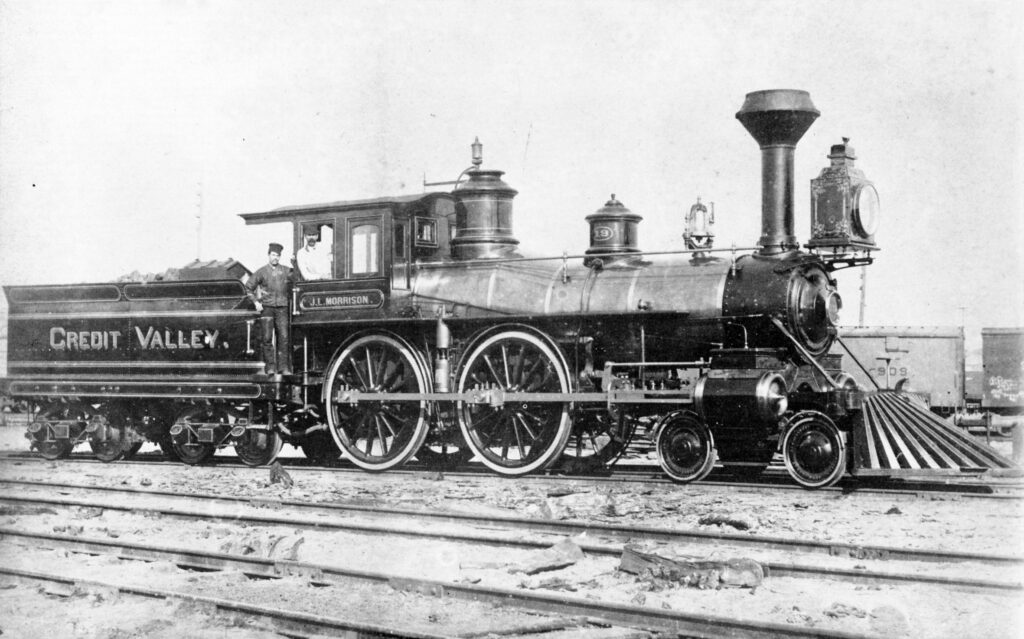

The Credit Valley’s conflicts with Grand Trunk continued to flare anew. For several months in 1881, CVR withdrew from Union Station, either because they were evicted or they objected to the onerous terms extracted by Grand Trunk for the use of this facility. Effective April 18th, the Credit Valley announced that their passenger trains would utilize Northern Railway’s City Hall station at the foot of Jarvis Street. Since the Grand Trunk blocked access along the Esplanade, this never occurred. Instead the Credit Valley began using the Northern’s Brock Street (Spadina) station on May 4, 1881. Despite these difficulties, business was booming for the Credit Valley although their financial woes would continue throughout the company’s existence. The CVR moved into a new downtown ticket office at 20 King Street West and established an omnibus and baggage wagon service between there and the Brock Street depot. In the spring of 1881, the railway purchased eight new locomotives from the Kingston Locomotive Works as well as a number of luxurious new passenger cars. On September 5, 1881, Credit Valley apparently resolved its difficulties with Grand Trunk and moved back into Union Station. The timing was probably related to the CVR’s completion of its 121-mile main line to St. Thomas. Regular passenger service from Toronto Union Station resumed on September 22, 1881.

In St. Thomas, the CVR interchanged with the Canada Southern Railway at their magnificent Italianate train station completed in 1873. The Canada Southern operated across southern Ontario, connecting Buffalo, New York and Detroit, Michigan. The Railway was controlled by William K. Vanderbilt, and formed a part the sprawling New York Central empire-reaching Detroit, Toledo, Chicago and St. Louis. The records and timetables indicating the consist of passenger trains on the Toronto- St. Thomas route during the three years it was under Credit Valley control are incomplete. A January 1882 Canada Southern timetable shows no through cars from Toronto operating beyond St. Thomas, but a CVR timetable for October 1883 does indicate through coaches operating from Toronto to Chicago. Credit Valley owned a number of sumptuous parlor cars that were in service between Toronto and St. Thomas but, again, the record is fragmentary. These cars were available to any first class passenger and there is no record of them being used on the Elora or Orangeville branches. There may have been a half dozen of these cars, some featuring 13 reclining chairs, drawing room, smoking room, lavatory and retiring room. Two of the cars were the ‘Humber River’ and ‘Grand River’, named after the most impressive waterways spanned by the railway and built by the Jackson & Sharp Company in 1882. There was also a ‘Credit River’ and a ‘Thames River’ and possibly two others, including the ‘Ninth River’. The Cobourg Car Works of Cobourg, Ontario, built one of these cars. There is some evidence that two other parlor cars were purchased used from the New York Central Railroad and one of these was renamed ‘Victoria’, although there is no river in Ontario honouring the reigning monarch at that time. There is further evidence that these cars were modified with a rounded end in an early attempt at aesthetic streamlining.

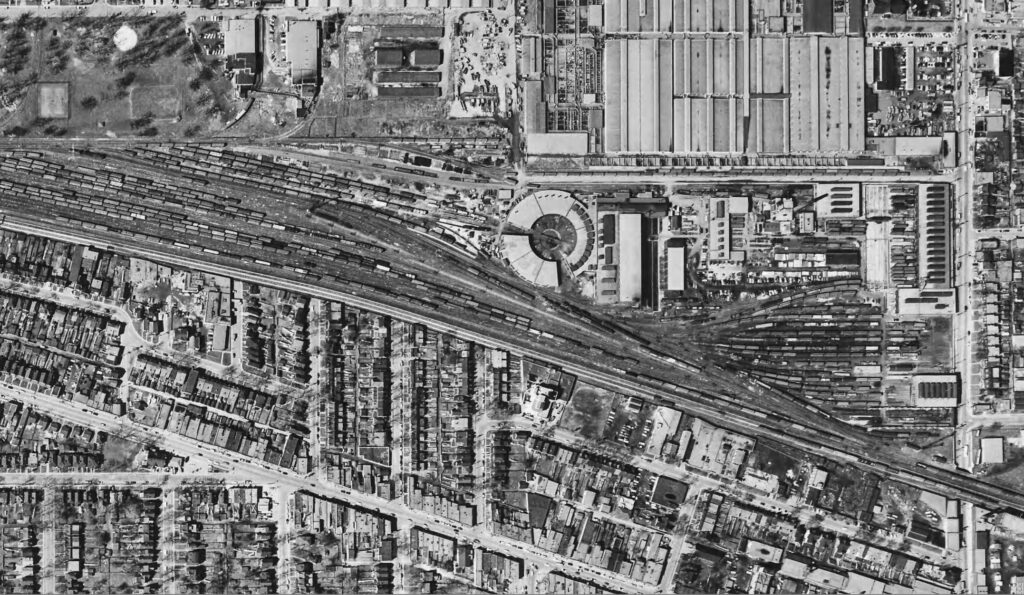

The CVR regularly expanded their terminal facilities in Parkdale. In 1881, the railway completed a 61×51 foot blacksmith shop, a 190-foot long car shop and tool shed with three tracks, a 132-foot long paint shop, a freight house, and a roundhouse. The railway only enjoyed the use of the new roundhouse for a few months before it was destroyed in a fire on April 25, 1882. Four engines were also damaged and the loss was estimated at $40,000. Ontario’s blue laws continued to impede railway growth and profits and they proved to be a massive inconvenience for passengers. In the first decades of the railway era, trains simply did not operate on Sunday. When the Grand Trunk established overnight trains between Montreal and Toronto in 1857, trains departing each terminal on Saturday night were forced to lay over in Kingston all day Sunday, not able to resume their journeys until after midnight on Monday morning. This proved to be a hindrance to the expeditious delivery of Dominion Post Office mail and the federal government passed legislation permitting trains that carried the mails to operate on Sunday.

In October 1881, Credit Valley Railway tested the blue laws by establishing a Sunday morning train that departed Toronto Union Station following the arrival of Grand Trunk No. 4, the overnight train from Montreal. Soon notices began to appear in local newspapers urging people to “help stamp out this pernicious and lawless traffic by not traveling on this train.” So strong was the public outcry that the CVR discontinued the train in November after a public apology from superintendent James Ross. In 1883 Ross became manager of construction through the Rocky Mountains for the Canadian Pacific Railway. He was a prominent figure in the famous photograph taken during the Last Spike ceremony at Craighellachie in 1885. Later Ross became a wealthy capitalist and a key figure in building the streetcar systems in Toronto and Montreal.

The Canadian Pacific Railway Shows Interest

On May 26, 1881, three of the most important officials connected with the Canadian Pacific Railway, Donald A. Smith, George Stephen, and R.B. Angus returned to Montreal from an inspection trip to Winnipeg by way of Chicago. Their special train was routed over the CVR. When their train covered the 21 miles from Streetsville to Toronto in 24 minutes, they were reported as being “highly pleased with the line.” The CPR recognized the importance of the Credit Valley as the foundation of a trunk line through southern Ontario facilitating the movement of a vast amount of traffic from west of the Great Lakes to the Eastern Seaboard. It was not publicly known at the time, but George Stephen was in fact already deeply involved with the affairs of the Credit Valley Railway, although as a personal investor, not in his capacity as the Canadian Pacific Railway’s first president. Stephen had arranged financing and purchased over $1 million of CVR debentures from his good friend George Laidlaw in order to facilitate the completion of the line. In 1884, Stephen would use these personal bonds to help guarantee financing for the construction of Canadian Pacific’s transcontinental line during the railway’s most threatening financial crisis.

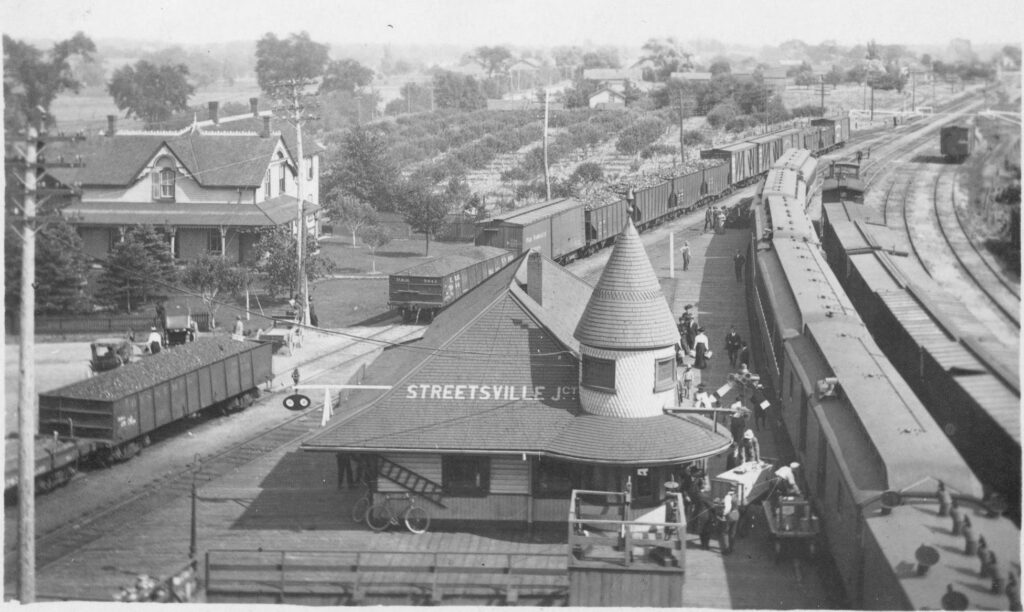

On September 11, 1881, another group of CPR officials returning from Winnipeg flew over the nineteen miles of CVR from Streetsville to Parkdale in nineteen minutes. Upon their arrival in Toronto, a meeting was held in the Queen’s Hotel on Front Street to discuss a possible merger of four railways: Great Western; Ontario & Quebec; Credit Valley and Toronto, Grey & Bruce. The last was particularly desired for its Georgian Bay port at Owen Sound, which would provide steamship connections to western Canada and a supply route for the construction of the CPR’s transcontinental line along the isolated north shore of Lake Superior. The Grand Trunk was understandably mortified at the prospect of this merger. A mighty corporate struggle ensued for the next several years as the GTR and CPR competed to purchase, control and consolidate southern Ontario’s smaller railways into their own systems. Initially, the Grand Trunk appeared to have the upper hand with its takeover of the Toronto, Grey & Bruce in 1881, whereupon the GTR undertook the conversion of the 3’6” gauge railway to standard gauge. The Grand Trunk then turned its attention to the Great Western Railway. For many years, the GWR had been the second most important railway in the province, connecting Toronto with Hamilton and the Niagara peninsula, where a bridge over the Niagara Gorge provided direct rail access to New York and the U.S. eastern seaboard. From Hamilton, GWR extended west to London, Windsor and the Midwestern U.S., using a car ferry link across the Detroit River. During the summer of 1882, the Grand Trunk concluded what amounted to a hostile takeover of the Great Western.

The Grand Trunk now had control of all lines connecting southern Ontario with the U.S. except one, the Canada Southern Railway, which was controlled by the New York Central’s William K. Vanderbilt. While in New York, George Stephen had arranged with the American rail magnate an interchange between the Canada Southern and CVR at St. Thomas. From there, traffic was forwarded on to Amherstburg, 20 miles south of Windsor, and by ferry and bridges across the Detroit River into the U.S. In 1883, Vanderbilt extended the Canada Southern trackage to Windsor and relocated the Michigan Central car ferry crossing to the Windsor- Detroit area. By June 1882, passenger traffic on Credit Valley had so increased that it had to borrow surplus cars from Canada Southern. The CVR annual report for the year ending June 30, 1882 showed an inventory of 3 engine houses and shops, 19 engines, 12 first class and 9 secondclass cars, 8 mail-baggage-express cars, 250 cattle and box cars, 195 flat cars and 13 lime cars. Not included in the inventory were a number of passenger cars under construction at the Cobourg Car Works when an 1881 fire destroyed two buildings in which the cars were being built. Also lost in the conflagration was an elegant Credit Valley official car valued at $8,000. The Cobourg Company did manage to deliver a dozen cars to CVR, including a first class coach that survived in work train service until 1954, when it was scrapped at West Toronto.

The connections with U.S. railroads in southwestern Ontario weren’t just important because of the opportunities for Canadian railways to capture traffic originating in the Midwest and travelling directly through Canada to the Eastern Seaboard. Until the opening of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s line north of Lake Superior in 1885, these connections also provided the only all-rail route between eastern and western Canada. In this capacity, Credit Valley Railway played a role in the settlement of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. A Toronto real estate developer named John T. Moore established the Saskatchewan Homestead Company and chartered “solid express special” trains to convey settlers 1,720 miles from Toronto to Crescent Lake, about 100 miles northeast of Regina. The first train departed from Union Station on March 29, 1883 via Credit Valley Railway while its progress to the west was breathlessly reported by Moore in a series of ads published in the Globe. As well as a list of the settlers, the ads also provided details on the CVR train itself (Engine No. 14, Driver John Carey, 1 platform car, 1 box car, 8 combination cars, 1 baggage car, 1 coach). The train was routed via a handful of American roads, finally completing its 4-day, 18-hour journey (“The Quickest Trip on Record”) over the newly laid tracks of the Canadian Pacific Railway as far as Broadview, Saskatchewan. It’s not known to what extent Moore was able to deliver on his promise to the settlers of “happy homes on fertile farms” as Louis Riel’s North-West Rebellion was about to erupt not far from Crescent Lake. Moore himself was later the principal promoter of the Toronto Belt Line Railway, whose grandest station was located at Moore Park, now one of Toronto’s more exclusive residential neighbourhoods.

Construction on the Ontario & Quebec Railway began in 1882 but was thwarted by the Grand Trunk’s continuing chokehold on rail access to downtown Toronto and the waterfront. The O&Q then bypassed Toronto by building their line north of the city limits from Leaside in the east, westward along the foot of the ancient Lake Iroquois shoreline, through the village of Yorkville to a meeting point with the CVR, which was named West Toronto Junction. At this location near Keele St. and Dundas Street West, the company built a station and would later build a freight yard and locomotive facilities. This site was still five miles northwest of the central business district and the Grand Trunk was determined to use every legal machination at its disposal, as it had against the CVR, to prevent the upstart Ontario & Quebec from accessing the waterfront and the city centre. There has been some speculation that the Credit Valley Railway came under the control of the Great Western, and later Grand Trunk, when those two railways amalgamated in August 1882. James Filby in his book on the CVR quotes a Chicago newspaper article in which a Great Western executive claims that GWR leased CVR for 999 years. This author has found no further corroboration that such an arrangement ever existed. None of the other published works on any of the three railways mention it, nor does Canadian National’s thorough Synoptical History, which records in minute detail every corporate arrangement of its constituent railways. One can only assume that Great Western had its own reasons for planting such a story.

The CPR Takes Over

In any event, the Grand Trunk’s own financial difficulties caused it to lose control of the Toronto, Grey & Bruce, a situation exacerbated by the expensive conversion of the line to standard gauge. Consequently on July 26, 1883 TG&B was leased to the Ontario & Quebec Railway. On November 30th, the Credit Valley was added to the Ontario & Quebec holdings. The corporate maneuvering ended when all three railways were leased to Canadian Pacific on January 4, 1884. They became part of the CPR’s Ontario Division on May 1, 1884. The CPR purchased a building on the southeast corner of King and Yonge streets, where it consolidated the Toronto headquarters of the three railways and opened a downtown ticket office. An office for W.C. Van Horne was also fitted out on the second floor. It’s not known how much time he spent there since he was constantly on the move while finishing construction of the transcontinental railway from Montreal to the Pacific Ocean. However, there is at least one recorded instance where the general manager took a personal interest in disposing of Credit Valley assets. In 1926, a retired Canadian Pacific executive named Alfred Price wrote in his memoirs that Van Horne had visited the Parkdale yards some time after the consolidation and spotted the two parlor cars that the CVR had purchased from the New York Central, which by this time were quite dilapidated. “One day, Mr. (W.C.) Van Horne was passing through the yard with Car Foreman Joe O’Brien, saw the cars and asked about them, and when told of the condition they were in said, ‘Burn the damn things!’ and before he had left the premises, the order was carried out.”

The Canadian Pacific quickly made several post-amalgamation modifications. Between Toronto and Orangeville, they now had two separate lines, both of which remained in operation. However, CPR favoured the TG&B terminal facilities in Orangeville and abandoned the 3.3 mile parallel Credit Valley track south from there to Melville Junction on January 18, 1884. This was probably the first Canadian Pacific track abandonment anywhere in Ontario. In 1883 , the CPR had established a steamship service on the upper Great Lakes, with Owen Sound harbour as the eastern base. Initially this operation served primarily as a supply route for the construction of the transcontinental railway along the north shore of Lake Superior. Beginning in 1884, regular commercial steamship operations began with special ‘Steamship Express’ trains conveying passengers between Toronto and Owen Sound. Although these trains operated mostly over Toronto, Grey & Bruce tracks, at least one timetable from 1887 shows a boat train routed via Streetsville and the Credit Valley. The steamship expresses via Orangeville were continued until 1912 when the eastern steamship base was moved from Owen Sound to Victoria Harbour, which was then renamed Port McNicoll, after David McNicoll, the CPR Vice-president in charge of Ontario operations.

On April 21, 1884, the CPR introduced a Palace sleeping car between Toronto and Chicago. This would have increased the range of available accommodation to passengers as only parlour cars had previously operated between Toronto and St. Thomas on the CVR. Although CPR was acquiring its own roster of sleeping cars, those in international service were usually provided by the US connections. Since the sleeper was routed over the Michigan Central west of St. Thomas, the Palace car was provided by the New York Central Sleeping Car Company established by Webster Wagner, who two years earlier had been killed by a rear end collision while riding in one of his own sleeping cars. The Canadian Pacific inaugurated passenger service between Montreal and Toronto on August 11, 1884. The railway promoted its twice-daily Montreal- Toronto-Detroit-Chicago passenger service via the CVR, although it’s likely that this consisted only of through sleeping cars routed on different trains since it owned no track west of St. Thomas. This CVR connection with the Michigan Central was particularly irksome since CPR missed two of southwestern Ontario’s most important cities: London and Windsor. The West Ontario Pacific Railway was incorporated in 1885 to build the ‘Detroit Extension’ west from Woodstock. The line to London opened in 1887 and on to Windsor in 1890, where CPR established its own car ferry service across the Detroit River with two side-wheelers, ‘Ontario’ and ‘Michigan.’ The former Credit Valley main line between Woodstock and St. Thomas then became a secondary branch line.

Back in Toronto, the upper floor of the Credit Valley’s Parkdale station became the headquarters for CPR train dispatchers in Ontario. Hanging on the office wall was a macabre reminder to train crews of how dangerous their job could be. In plain view was the skull of cow that had derailed a Credit Valley train and caused the railway’s first fatal accident, killing both the engineer and fireman. This morbid object apparently assumed iconic status in Toronto since a plaster replica was also on display in the CPR offices at King and Yonge streets. In 1885, the CPR made some improvements at Parkdale. A new switch was installed near the Central Prison so that westbound passenger trains didn’t have to back into Parkdale station. A new 65-foot turntable was also installed to replace the wooden one, which, according to the Globe, “while it satisfied the requirements of the Credit Valley, is much too small and weak for the requirements of through traffic.” A new steam lathe for leveling locomotive wheels was also installed. The Credit Valley Railway’s most significant contribution to North American railroading occurred months after its takeover by CPR.

On April 1, 1884 the world’s first rotary snowplow was tested along the track between Parkdale and Queen’s Wharf. In the first decades of the railway era, winter operations were often crippled by snowstorms. The wedge plow merely pushed the snow aside but when there was a heavy snowfall, trains were often stranded until labourers could dig them out with shovels. The new rotary snowplow employed a large steam-powered cutting wheel and a specialized fan that digested the snow and propelled it well off to the side of the track. Although technical details of the first rotary plow are sketchy, the machine appears to have been constructed in the CVR’s Parkdale shops. Since it was late in the winter season, a gang of men was sent out with shovels to gather up enough snow from dark corners and shady locations. Once perfected, the rotary plow could cope with much deeper snow than previously and railways were no longer shut down for days at a time except in the most extreme circumstances.

The CVR’s most enduring legacy in Toronto to this day is the Credit Valley sandstone that was quarried at Forks of the Credit and transported into Toronto on CVR flat cars. This pleasing reddish-brown stone was used to clad some of the city’s most prominent structures, including the Ontario Parliament Buildings at Queen’s Park (1892) and Old City Hall (1899). Vanished landmarks, that utilized this stone included Toronto’s first true skyscraper – the Temple Building (1902-1970) – and the Front Street headhouse of the third Union Station (1896-1931). In 1881, an average of 18 carloads of this stone was being transported into the city every day. In 1887, the timber truss bridge over the Humber River was replaced with a new iron span. The line from Lambton to the west was double-tracked in 1911 but the gantlet bridge over the Humber remained a traffic bottleneck until it too was rebuilt with two tracks in December 1914. This was the last remaining length of single track between Leaside and Guelph Junction. Although the piers were extended and strengthened with concrete, the original 1874 Credit Valley stonework can still be clearly seen. In the years after the CPR absorbed the CVR, the railway gradually relocated the Parkdale locomotive and maintenance facilities elsewhere.

Passenger engine servicing was moved downtown in 1897 to the new John Street roundhouse, which was located just west of where the Credit Valley had erected its waterfront freight shed. Freight locomotive and heavy-duty engine maintenance was shifted to West Toronto, with only a car shop and freight yard remaining at Parkdale. Around 1910 the Parkdale freight yard was expanded and the north-south track arrangement built by CVR was changed to an east-west alignment. After the 1964 opening of Toronto Yard in Scarborough, Parkdale remained busy as a sorting yard for local freight trains switching industries in downtown Toronto. In the 1970s and 80s, these industries gradually closed down or relocated to the suburbs. On March 16, 1986, the last local freight train departed from Parkdale and the yard was then used for intermodal container traffic until it closed for good in October 1990. In 1885 Parkdale became the site of Toronto’s first grade separated crossing, or subway, as it was then known. With several tracks of each of four different railways crossing over Queen Street, this location had become a serious safety hazard and a hindrance to Toronto’s westward development. As the city expanded, the demand for subways increased and a number of massive grade separation projects were carried out, culminating in 1930 with the completion of what is now known as the Union Station Rail Corridor.

The Credit Valley’s Parkdale passenger station survived until 1911 when it was replaced by a brick structure that remained in use until 1968. Following the CPR takeover in 1884, the Toronto, Grey & Bruce line through Bolton became the preferred route between Toronto and Orangeville rather than the Credit Valley line, even though it had easier grades, more generous curves and higher engineering standards. This seems puzzling today as the CPR certainly recognized the limitations of the Toronto, Grey & Bruce route and there were at least three surveys and two proposals to realign the route before the turn of the 20th century. The railway had cause to regret their dithering on September 3, 1907 when a CPR ‘Exhibition Special’ derailed on the scenically spectacular, but dangerous, Horseshoe Curve near Caledon, killing seven and injuring 114.

The Toronto, Grey & Bruce had built the sharp curve around 1870 in order to ascend the Niagara Escarpment while saving money on engineering and construction. However, it wasn’t until 1932 that CPR abandoned the 19 miles between Bolton and Melville Junction and the former CVR line became the sole route between Toronto and Orangeville. The Elora Branch was the least profitable component of the CVR. Plans to extend the line to Elmira never came to be although the branch remained open for over a century. With freight traffic down to less than twenty carloads a year, the CPR abandoned it in 1987. Today it has been transformed into the Elora Cataract Trailway, a recreational path. Otherwise most of the Credit Valley right-of-way remains in operation.

Passenger Service Along the CVR in the CPR Era

Following the completion of the Detroit Extension in 1890, which caused a falling out with Michigan Central, the CPR made arrangements with the Wabash Railroad to provide through service beyond Detroit to Chicago. This arrangement prevailed until 1914 when the CPR began using the Detroit River Tunnel and the newly completed Michigan Central Station in Detroit.

On May 31, 1914, CPR inaugurated ‘The Canadian’, a Montreal-Chicago train that featured through standard and tourist sleepers, coaches, and a buffet-library-compartment observation car, probably one of the Glen cars built in the company shops in 1909. ‘The Canadian’ remained the most prestigious train on this route until the name was appropriated for the CPR’s new transcontinental streamliner in 1955. Other name trains operating over the CVR line west of Toronto included the ‘Chicago Express’, the ‘Royal York’, and the ‘Overseas’. In 1936, following several years of Depression-induced austerity, the CPR introduced four new streamlined trainsets for fast intercity medium-distance passenger routes. The semi-streamlined 4-4-4 locomotives were dubbed “Jubilees” in tribute to the 50th anniversary of the commencement of transcontinental train service in 1886. The trainsets each consisted of a mail-express car, a baggage-buffet-coach and two coaches built at the National Steel Car Co. in Hamilton and CP’s Angus Shops in Montreal. On September 27, 1936, two of these locomotives and one trainset were placed in service on the Royal York between Toronto and Detroit, reducing the travel time between the two cities to 5 hours, 35 minutes.

In 1953, Canadian Pacific introduced Rail Diesel Cars along the Toronto-Detroit corridor. These ‘Dayliners,’ as CPR marketed them, would replace the 3000 series Jubilee steam locomotives used on this route since 1936. The RDC’s were manufactured by the Budd Company in Philadelphia, the same firm that provided the stainless steel fleet for the new ‘Canadian’. Heavy passenger trains remained the norm along the Toronto-Detroit main line throughout the 1950s. With the building of Highway 401, rail patronage evaporated and Dayliners completely took over this service by 1964. The two daily round trips were cut back from Detroit to Windsor in 1967 and reduced to one a day in 1969. The Toronto-Windsor trains were eliminated on July 3, 1971, ending all CPR passenger service over the former CVR and in southwestern Ontario. Passenger traffic was seldom abundant on the Elora branch. The passenger trains were replaced by a mixed train in 1920, which was terminated in 1957. By 1958 Dayliners were providing all passenger service on the Toronto-Orangeville-Owen Sound route. The two daily round trips were reduced to one a day in 1961, and three times a week by 1964. The trains were cancelled on October 30, 1970, ending CPR passenger service over the Streetsville-Orangeville segment of the CVR.

On October 26, 1981, GO Transit initiated commuter service over the old CVR main line between Milton and Toronto Union Station with three rush hour round trips on weekdays only. It is currently the only GO train route operating mostly over Canadian Pacific tracks. Today, it is the second busiest GO corridor with seven trains a day in each direction. It is scheduled to see all day service in the near future. In 1995, Canadian Pacific abandoned the former Toronto, Grey & Bruce line from Orangeville north to Owen Sound. Following a failed attempt to convert it into a short line, the track was taken up in 1997-98. In 2000, the Town of Orangeville purchased the former Credit Valley Railway from a point 2.4 miles north of Streetsville to mile 36.7, just north of Orangeville. Dubbed the Orangeville Brampton Railway, the town engaged Cando Contracting Ltd to operate the line and deliver resource materials to local manufacturers via the CPR interchange at Streetsville Junction in Mississauga.

In 2011 the town was negotiating to sell the line to the Highland Railway Group of private investors. Recently, GO Transit purchased the lower 3.5 mile section of the CPR’s Galt Subdivision from the west end of the Toronto Terminals Railway at Strachan Avenue to West Toronto. The Ontario Southland Railway acquired the Woodstock – St Thomas trackage from the CPR and began operations over this track on December 14, 2009. Thus in 2011 the only part of the CVR still in CPR hands is the 83-mile Galt Subdivision from West Toronto to Woodstock.

Credit Valley Railway Revivals

For a railway company that disappeared in 1884, the Credit Valley enjoyed several moments in the spotlight well into the 20th century. On May 1, 1960, the famous “end of steam” triple-header steam locomotive excursion carried 1,100 people between Toronto and Orangeville. Two of the locomotives used on this railfan excursion, Canadian Pacific 4-4-0 No. 136 and 4-6-0 No. 1057, would continue to burnish Credit Valley rails in the 1970s.

The Ontario Rail Association was formed in 1972 with the objective of gathering steam-era locomotives and passenger cars, restoring them to operation, and establishing an operating heritage railway in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). The association acquired a fleet of heavyweight passenger cars and the two locomotives were restored at CPR’s John Street roundhouse. The first excursion in 1973 operated between West Toronto and Orangeville. Since most of the equipment was Canadian Pacific, the group decided to call the operation the Credit Valley Railway in homage to the original and to name the passenger cars after various CVR stations. Over its first three years, the group operated 23 excursions in the GTA. Their search for a permanent home was thwarted by vociferous NIMBYism from local residents who considered a steam train operation to be too “dirty.” The excursions proved unsustainable in the long term and the locomotives and rolling stock became part of the South Simcoe Railway tourist train operation in Tottenham, where they remain today. At the same time that ORA was operating its excursions, the old CVR played a substantial role in Canadian publishing that has benefitted the rail enthusiast community in recent years. In 1974, James Filby wrote a small book about the CVR, “The Third Giant”. When Filby could find no one willing to publish it, he started his own publishing company called Boston Mills Press. It has since become one of Canada’s leading publishers of local histories and high quality railway titles. Even in the 21st century, the name of the Credit Valley Railway lives on today in two local landmarks well known by rail aficionados. In 2004, the Orangeville Brampton Railway introduced seasonal excursion passenger service, which it brands as the ‘Credit Valley Explorer.’ The highlight of the trip is still the view from the railway trestle bridge, now mostly filled in, that spans the Credit Valley and the Forks of the Credit River and Provincial Park at Cataract. Just as they did 130 years ago, city dwellers can appreciate the delights of the Credit Valley – this time while enjoying a fine meal and historical commentary. The Credit Valley Railway is also the name of one of the Toronto area’s most popular model train shops. After many years in Streetsville, the shop recently relocated to Mississauga. One would be hard put to find another defunct 19th century Canadian railway still recognized by more than a handful of rail historians 125 years after it ceased to exist.

Written by Derek Boles, TRHA Historian, who retains copyright on the content. These pages are not to be reproduced without written permission.