Introduction

A modern-day fixture of commerce and transportation in Canada, the Canadian Pacific Railway’s beginnings as the country’s first transcontinental railway have been retold by countless authors and creators in a variety of mediums. While the construction of the railway through the Rocky Mountains often gets most of the limelight, Canadian Pacific’s early history in southern Ontario is somewhat overlooked by comparison. Through support from the federal government, the Canadian Pacific Railway was able to slice through the province and effectively end the monopoly of the long-established Grand Trunk Railway in the process. Canadian Pacific’s presence in Toronto would grow rapidly in the following years, fomenting a vicious rivalry with the Grand Trunk that would continue under its successor Canadian National. In more recent years, Canadian Pacific would hand off their remaining passenger service to federally-run VIA Rail, joining other Class I railways in North America in focusing their efforts entirely on freight service. It was announced in 2021 that Canadian Pacific intended to merge with the Kansas City Southern Railway and its Mexican subsidiary, Kansas City Southern de Mexico. The company rebranded as Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) in 2023 shortly after the merger, marking the most significant change in Canadian Pacific’s corporate identity since its formation.

A False Start

On July 1st, 1867, the British North America Act went into effect. The British colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the Province of Canada were merged into the Dominion of Canada – a semi-autonomous dominion of the British Empire. Over the previous decade and a half, railways had only just begun to establish themselves within Canadian territory. However, this statement alone somewhat undersells the achievements made by Canadian railways up to that point. During the same period, the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada had briefly attained the title of the longest railway in the world. The viability of railways in Canada was becoming increasingly apparent, but it would be another few years until talk of a transcontinental railway began. In 1870, the colony of British Columbia sent its stipulations for joining Canada, one of which was the construction of a transcontinental railway to connect it with the rest of the country. John A. Macdonald’s government initially approached the Grand Trunk Railway to extend westward to the pacific coast. This was already an idea held by Edward Watkin, president of the Grand Trunk from 1862 to 1869. He was ousted from the company due to widespread internal opposition to this idea, and the Grand Trunk ultimately turned the government down. At the same time, Scottish-Canadian entrepreneur Hugh Allan sought to throw his hat into the ring. For his reputation with other successful business ventures in North America and for less scrupulous reasons that will soon be apparent, Allan ultimately won the contract to build the transcontinental railway. British Columbia officially joined Canada on July 20th, 1871, and Allan incorporated his Canadian Pacific Railway Company in June 1872.

The transcontinental railway was to ultimately avoid Toronto entirely, as Montreal was the most populous city in Canada at the time. Where Toronto relates to the transcontinental railway is with an entirely different company, the Ontario & Quebec Railway. It was chartered on April 14th, 1871 by Henry John Hubertus and Harry Abbott among others, but Hugh Allan would come to own 50% of the company’s shares. Its route was to connect Toronto with the newly established federal capital of Ottawa, passing through the communities of Peterborough, Madoc, and Carleton Place along the way. Presumably, Hugh Allan’s interest in this company was to connect it with his transcontinental railway. This would allow him to directly compete with the Grand Trunk and establish a foothold in southern Ontario while construction of his Canadian Pacific Railway was ongoing. The route of the Ontario & Quebec was surveyed by civil engineer George A. Keefer in March 1872, and his report contained numerous recommendations and predictions. Some, like his prediction that the line might soon require an additional main track to handle the expected volume of train traffic, would prove startlingly accurate. He also commented on the difficulties of reaching downtown Toronto, suggesting that the railway should enter the Esplanade at Palace Street – which would ultimately be acted upon two decades later. By 1873, the Ontario & Quebec’s proposed route had greatly expanded to include a branch from the Port Perry area to the shore of Lake Huron at Goderich Harbour. It would cross the Northern Railway of Canada in Newmarket and pass through the communities of Uxbridge and Orangeville. This expansion was extensively hyped up by the railway’s promoters, and an 1873 edition of the Guelph Evening Mercury reported that “[The Ontario & Quebec Railway] will be of the greatest benefit to [the] whole Province of Ontario”. The Huron Signal similarly cheered “Hurrah for the Goderich Extension of the Ontario & Quebec Road” in a headline from one of their editions. Unfortunately, it would soon appear that the celebration was premature.

On April 2nd, 1873, Liberal Party politician Lucius Seth Huntington exposed a large donation made by Hugh Allan to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald to secure his contract for the transcontinental railway. The so-called Pacific Scandal led to Macdonald’s resignation on November 5th of that year and the end of Hugh Allan’s Canadian Pacific Railway. Promotion of the Ontario & Quebec Railway continued into December of that year in spite of the scandal, but most mention of it dries up by the following month and the charter fell dormant as the Panic of 1873 took hold. Local business interests from Peterborough led by W. H. Scott formed the Huron & Quebec Railway in 1874 to run nearly the exact same route as the Ontario & Quebec. The company raised money from the communities it intended to pass through, but bad press soon befell the reputations of those involved. A pamphlet was published in Carleton Place accusing the Huron & Ottawa of corruption, referring to one of Scott’s associates as a “railway lunatic” and a “trickster”. The company’s name was changed shortly thereafter to the Toronto & Ottawa Railway, and a short stretch near Tweed was prepared for the construction of bridges and tracks that would ultimately never be put into place.

On Better Footing

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie, a short segment of the transcontinental railway was constructed by the Department of Public Works through the Canadian Shield near Thunder Bay. After John A. Macdonald’s victory in the 1878 federal election, the rate of railway construction began to accelerate. On October 21st, 1880, a contract was signed between the Macdonald government and a new Montreal-based syndicate unrelated to Hugh Allan’s. Consisting of George Stephen, James J. Hill, Duncan McIntyre, Richard B. Angus and John Stewart Kennedy, the syndicate agreed to build the railway for $25 million. It was incorporated as the Canadian Pacific Railway Company on February 16th, 1881, and the ownership of sections already built by the government was subsequently transferred to it. The Ontario & Quebec Railway was re-chartered on March 21st of the same year by several individuals affiliated with Canadian Pacific. It would only ever exist on paper, never having any locomotives or rolling stock of its own. Both companies were to directly connect with the Canada Central Railway, which itself would be merged into the CPR in June of 1881. The Ontario & Quebec Railway was to join the Canada Central in Perth, and work on the transcontinental railway commenced just west of the Canada Central’s northern terminus in Mattawa.

While Canadian Pacific was hard at work blasting through the rocky terrain of the Canadian Shield, the Ontario & Quebec was simultaneously establishing a foothold in the Grand Trunk Railway’s territory. First, they set their sights on some of the smaller railway companies operating in the area, which sent the Grand Trunk into a frenzy to do the same. Canadian Pacific initially intended to merge the Ontario & Quebec Railway with the Great Western Railway, Credit Valley Railway and the Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway, which was generally met with enthusiasm from those who feared the economic repercussions of a Grand Trunk monopoly in the province. The Great Western was to carry all of Canadian Pacific’s freight traffic bound for the midwestern United States. The Grand Trunk responded with a hostile takeover of the Great Western Railway on August 12th, 1882, and a hastening of negotiations with the Toronto, Grey & Bruce to gain control of it. The Grand Trunk had already been gradually acquiring stock and bonds of the Toronto, Grey & Bruce, including funding a complete conversion from its original 3-foot 6-inch narrow gauge to 4-foot 8.5-inch standard gauge which was completed on December 8th, 1881. However, the Grand Trunk’s acquisition of the Great Western Railway required it to sell some of its stake in the Toronto, Grey & Bruce to pay for it. On July 26th, 1883, the Ontario & Quebec Railway leased the Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway, followed by a lease of the Credit Valley Railway on November 30th of the same year. Both were leased for a period of 999 years, effectively turning them into perpetual components of the Ontario & Quebec and Canadian Pacific by extension.

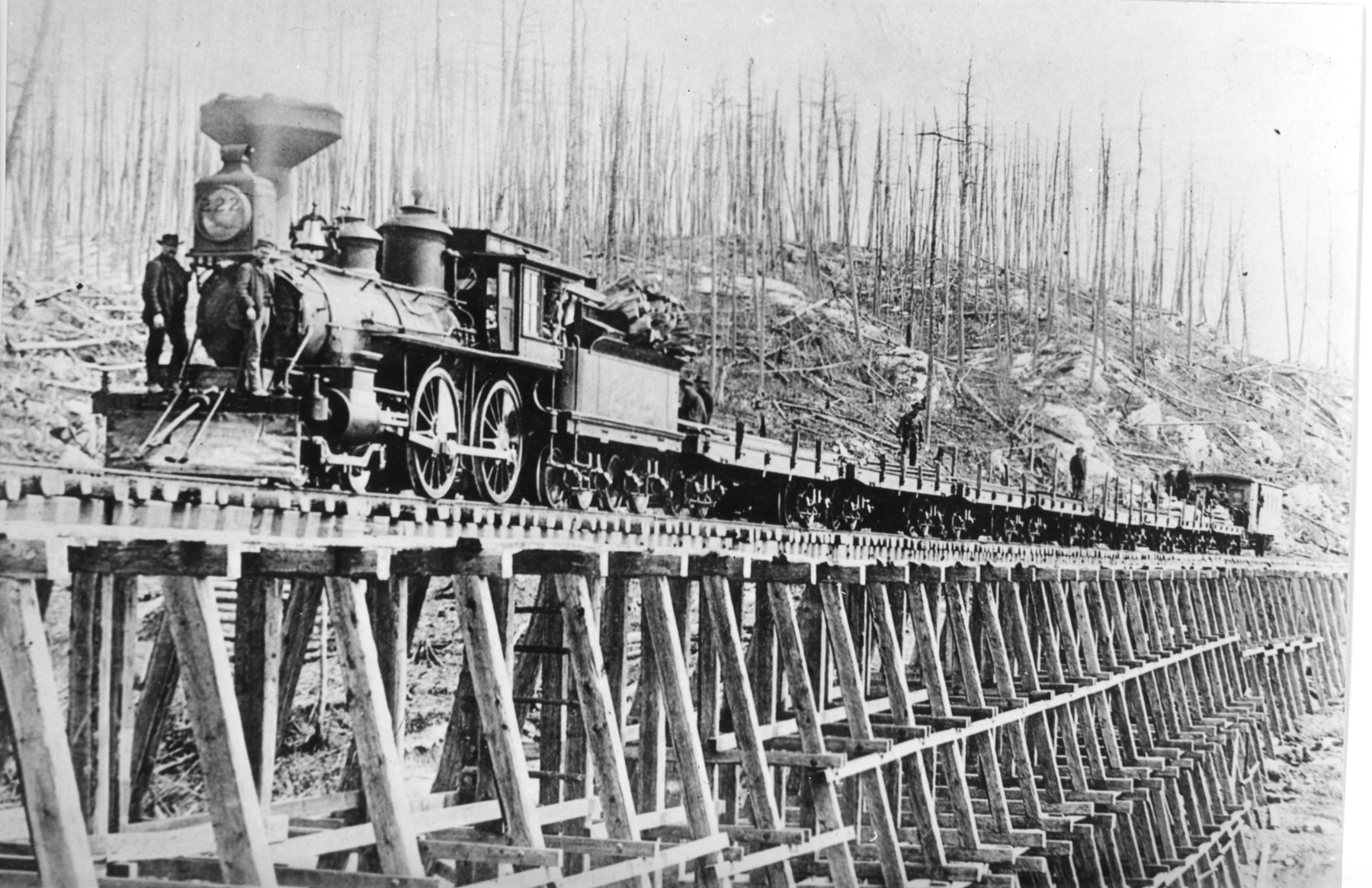

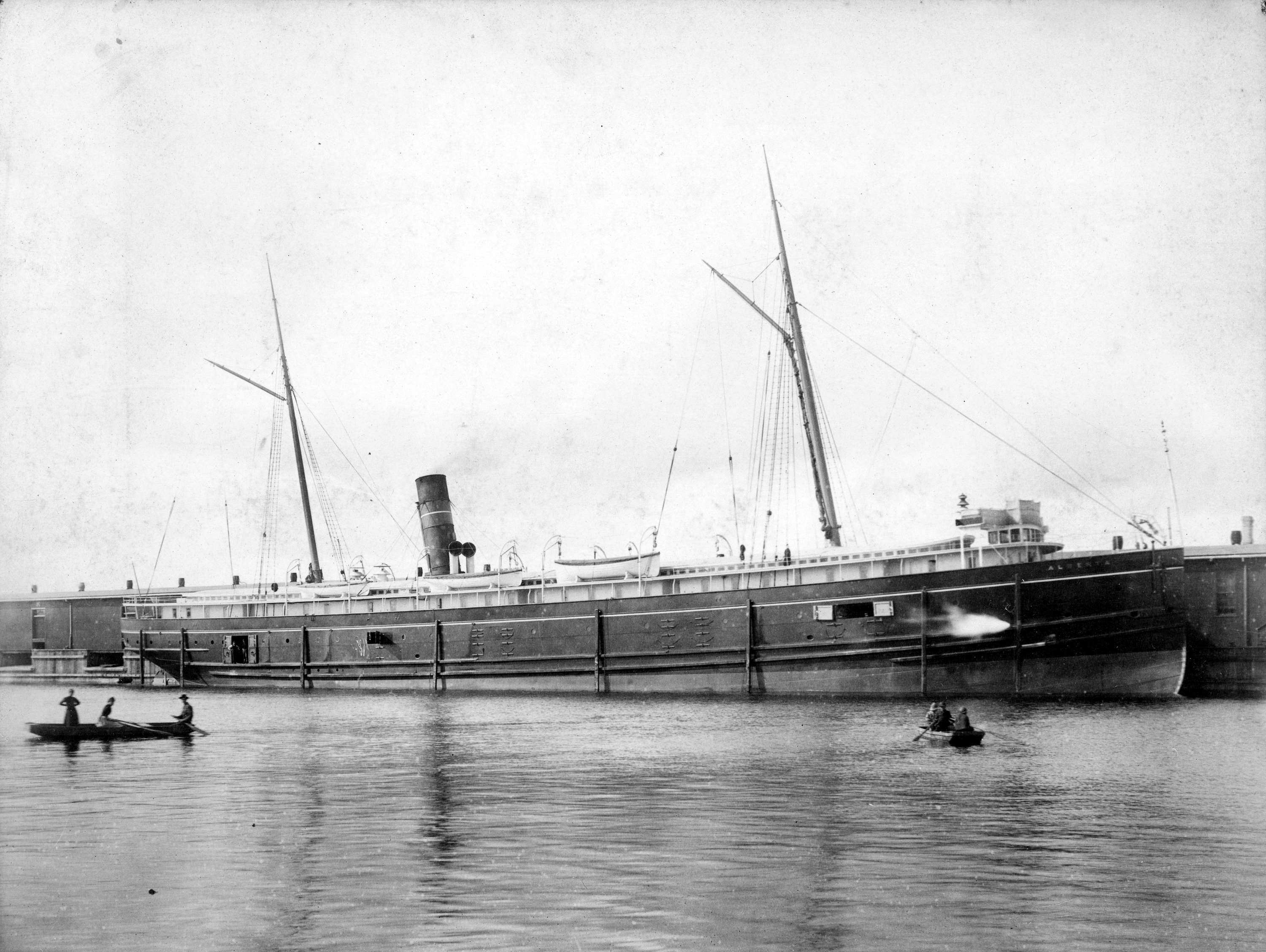

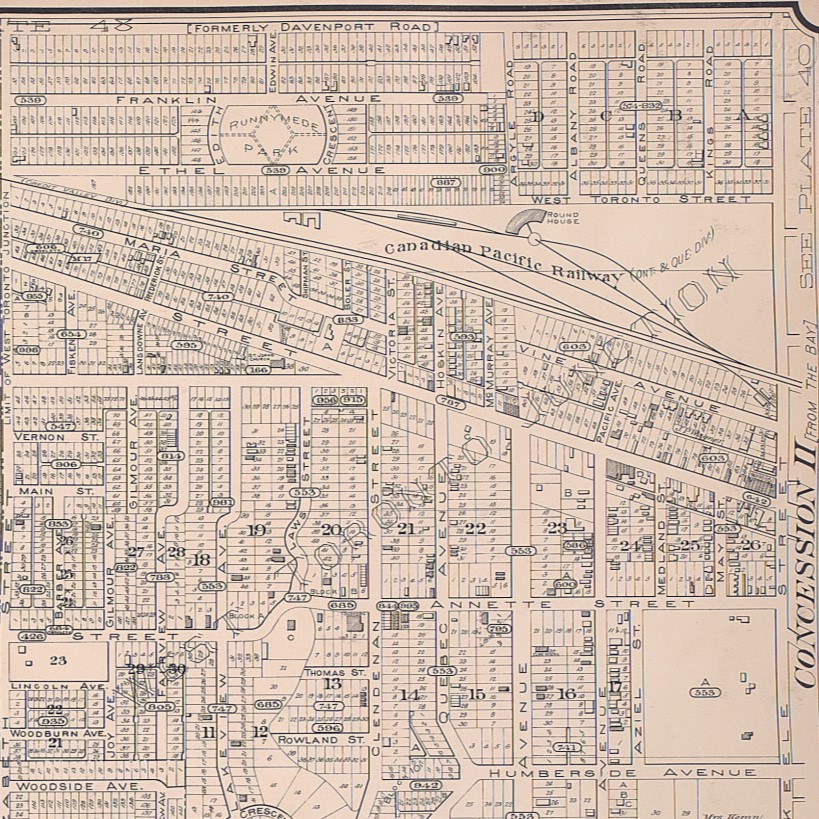

Simultaneously, workers of the Ontario & Quebec Railway had constructed 200 miles of track during 1883. It crossed both the Toronto, Grey & Bruce and Grand Trunk at grade before connecting with the Credit Valley Railway at a point called West Toronto Junction. A village of the same name was founded the following year in the junction’s proximity. West of the junction on the north side of the former Credit Valley right-of-way, the Ontario & Quebec Railway purchased 40 acres of land for the construction of new maintenance shops. In the meantime, a temporary maintenance facility was located at Leaside. An early passenger service was briefly established in September 1883 between a temporary station at North Toronto and the former Credit Valley station in Parkdale for the Toronto Industrial Exhibition. Months before the Ontario & Quebec Railway was finished, its shareholders voted unanimously to lease the company to the Canadian Pacific Railway during a special general meeting on January 3rd, 1884, for a period of 999 years.

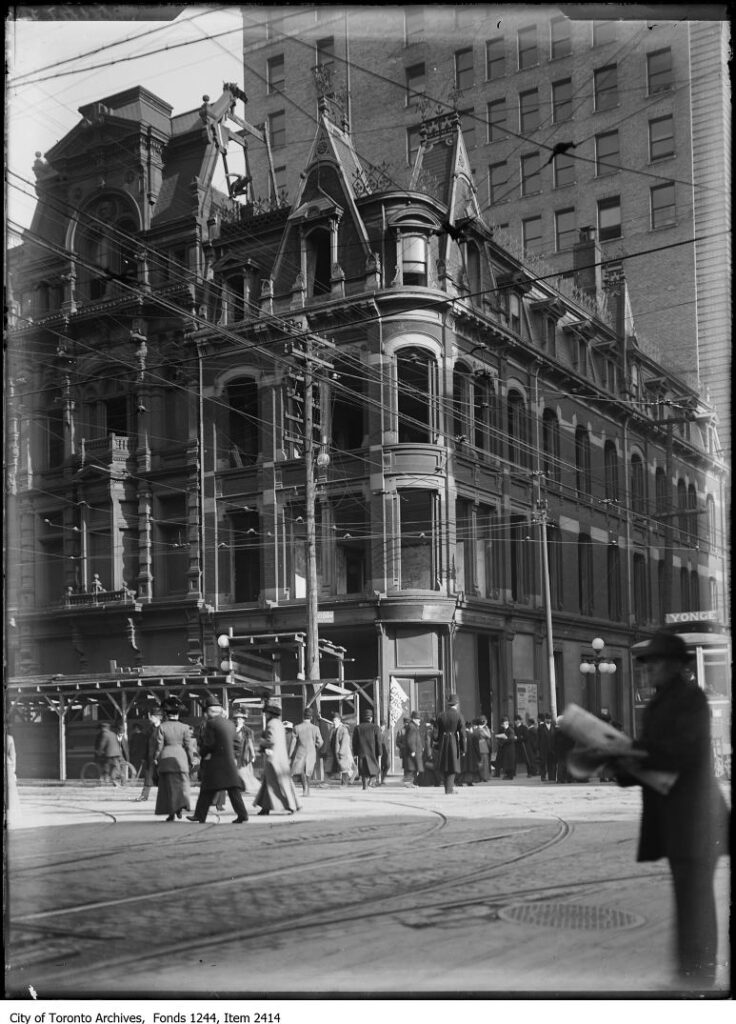

Its lease of the Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway enabled Canadian Pacific to begin offering a form of transcontinental passenger service between Toronto and Winnipeg – though not entirely through the use of trains. Steamships would be used on the Great Lakes in the meantime while rails were still being laid through northern Ontario, closing the gap between the TG&B Owen Sound docks and Port Arthur. Initially this was done through a fleet of second-hand steamships until three new ones were shipped to Canadian Pacific from Aitken & Mansell of Glasgow, Scotland. The steamships Algoma, Alberta, and Athabasca began regular service three times per week starting on May 11th, 1884. Passengers would take an express train from Toronto to Owen Sound, then transfer to one of these steamships to take them across Lake Huron and Lake Superior, and finally board another train in Port Arthur to continue westward. The Toronto-Owen Sound express train and Great Lakes steamship service remained fixtures of railroad operations in the Toronto area for many decades afterward.

Construction Superintendent Hugh Ryan drove the last spike of the Ontario & Quebec Railway at an unknown location approximately 8 kilometers (5 miles) east of Agincourt on May 5th, 1884. Just five days later, it was announced by the Toronto World that Canadian Pacific had paid an “exceedingly low” $22,000 (worth approximately $912,000 today) to purchase the former United Empire Club building at King and York Street for its local Toronto offices. The central room of the building’s second floor facing King Street was chosen to become the office of William Cornelius Van Horne, General Manager and soon-to-be Vice President of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Twice daily passenger service commenced between Toronto and Peterborough on June 28th, 1884, but through service beyond that point was delayed until August 4th due to a sinkhole near Kaladar. With the completion of the Ontario & Quebec Railway, Canadian Pacific now had the most direct route between Toronto and Ottawa, far outpacing any similar service offered by the Grand Trunk.

First Train to the West

Having now established a foothold in Toronto, albeit a suboptimal one, the Canadian Pacific Railway now set out to improve its facilities within the city. One of the first upgrades conducted by Canadian Pacific in Toronto was the replacement of the Parkdale roundhouse’s original wooden turntable with a 65-foot steel turntable in 1885. A parcel of land east of the Grand Trunk’s Union Station was purchased by Canadian Pacific during the same year with plans for an independent downtown terminal. These plans were filed on April 1st, 1886, and William Cornelius Van Horne stated in interviews that this land would be used for new passenger and freight facilities. He also mentioned that the company was actively attempting to secure a right-of-way to reach it.

On November 2nd, 1885, just five days before the last spike was famously driven at Craigellachie, the first all-rail passenger service between Toronto and the edge of the Rocky Mountains commenced. Scheduled to leave at 9:25 a.m. on weekdays, the train included a colonist sleeping car, elegant first-class cars, and a dining car. Making use of the newly completed transcontinental line in northern Ontario with stops in Port Arthur and Winnipeg, this train essentially duplicated the route of the CPR’s Great Lakes steamships. However, since the train departing from Toronto had to take an inconvenient jog east to Smiths Falls and Carleton Place, the steamships continued to remain somewhat popular especially outside of the winter months. In Carleton Place, the Toronto section met a separate train that departed Montreal on the same day at 2:00 p.m. They would then join together and run as a single train for the rest of the journey. Large crowds gathered to watch these trains depart, even in torrential rain in the case of Montreal. In contrast, the first Canadian Pacific train to Port Moody, British Columbia the following year on June 28th, 1886, was treated as a non-event in Toronto. An account from the Toronto Globe speculated that passersby at Union Station that day were simply unaware of its significance. It’s possible they mistook it for the regular weekday train to the Rockies that had been running regularly for seven months. The train was led by locomotive no. 305, with sleeping car Peterboro and a first- and second-class car behind it. Similar to the previous service, a separate section was run from Montreal and the two met at Carleton Place. The engines were swapped numerous times along the way, with the last being locomotive no. 371 on the final stretch from North Bend to Port Moody.

Back in Toronto, the efforts of Canadian Pacific to establish a proper terminal were ramping up. Arguably the most important addition sought by Canadian Pacific during this period was an eastern entrance into downtown. From the moment trains began running on the Ontario & Quebec Railway, passenger trains bound for Union Station and freight trains headed to the former Credit Valley facilities on the waterfront were forced to travel in reverse through Parkdale. In addition to a cumbersome and time-consuming process, this also presented a serious safety concern as most of the major streets through Parkdale still crossed the railroad at grade during this point in time. After a suitable route was determined to exist in the Don Valley, a Toronto City Council meeting on October 24th, 1887 resulted in granting Canadian Pacific the right to construct this line. On April 28th of that year, city officials negotiated the route of the so-called Don Branch with officials of Canadian Pacific for 22 hours. The result was a final decision on the route it would take, involving a junction with the Grand Trunk on the Esplanade at Parliament Street. The former Toronto & Nipissing yards at that location would need to be reconfigured at Canadian Pacific’s expense. The construction of the Don Branch would coincide with a project to straighten the lower Don River, which would provide more than enough space for the railway on its western bank. Construction of the Don Branch commenced towards the end of 1888 and first opened to freight traffic on September 7th, 1892. It took until May 14th, 1893 for passenger trains to begin using it as well.

Unfortunately for Canadian Pacific, their attempts to secure an independent downtown terminal were quashed by the city in 1888. Stuck with their existing relationship with the Grand Trunk at Union Station, it was immediately clear that the overcrowded 1873 station with only three tracks were wholly inadequate for the traffic it was expected to handle. On July 26th, 1892, the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Grand Trunk Railway entered an agreement to significantly renovate Union Station. In addition to expanding the interior space and adding more platforms, the rail corridor on either side of the station would be controlled by a complex mechanical interlocking system controlled by operators in four separate towers. The cost of the system was split evenly by both railway companies, and it would allow a significantly greater frequency of trains to move safely in and out. After these changes were completed on May 11th, 1896, Canadian Pacific set its sights on moving its locomotive facilities closer to downtown. In August 1897, construction began on a 15-stall roundhouse at the site of the former Credit Valley freight shed at the foot of John Street. This would replace the less conveniently located Parkdale Roundhouse, the turntable of which was moved to the new site. The new facility, which became known as the John Street Roundhouse, was completed on November 13th of the same year coinciding with the closure of the Parkdale facilities. It was positioned strategically to handle all passenger equipment between trips into or out of Union Station.

While John Street was responsible for passenger equipment, its counterpart at West Toronto would almost exclusively handle equipment used in freight service. This roundhouse was greatly expanded in 1891 to 31 stalls, nearly forming a complete circle around the turntable. A vast array of repair shops were also built to the immediate east of the West Toronto roundhouse, capable of conducting moderate repairs that didn’t require the larger repair shops in Montreal.

Closing the Gap

There were rumblings of a more direct all-CPR rail connection between Toronto and the transcontinental line almost as soon as Canadian Pacific began transcontinental service. Numerous independent railway companies had sought to connect Toronto with the transcontinental railway as early as the 1870’s, but the only one that was successful was the Northern and North Western Railway. Using the charter of the Northern & Pacific Junction Railway, it reached North Bay just in time for the opening of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1886. This cut the distance a train originating in Toronto would take by almost half, from 444 miles down to just 223 miles. While the passengers carried over this route were largely destined for Canadian Pacific, competition was still a concern. It was only exacerbated when the Grand Trunk Railway gained control of the Northern and North Western Railway in 1888. This naturally put Canadian Pacific in a precarious position. Both companies would eventually enter an agreement on July 26th, 1892 in which the Grand Trunk would handle Canadian Pacific traffic between Toronto and North Bay, making Canadian Pacific wholly dependent on the Grand Trunk to maintain its timeliness. The problem reared its ugly head when the Grand Trunk cancelled the agreement in January 1898 and all CPR traffic was forced to take the long way through Smiths Falls once again. It only took until March 16th of that year before officials from Canadian Pacific announced their intentions to build their own line through the same area, with the headline of the Toronto World triumphantly proclaiming, “The Toronto-to-Sudbury line is no longer a myth”. Surveying of the route was completed that year, but further planning was still necessary. However, the Grand Trunk saw the threat such a line would pose to their leverage and on November 11th, 1898, they relented by providing Canadian Pacific with running rights to North Bay. As a result, efforts by Canadian Pacific to build their independent line to Sudbury would slow for the time being.

However, a new competitor would soon be on the doorstep of both Canadian Pacific and the Grand Trunk in Ontario. William Mackenzie and Donald Mann, two former contractors of Canadian Pacific, had recently begun purchasing railway and streetcar companies across Canada. They would attempt to unify many of these companies into a single, country-wide system on par with that of Canadian Pacific. On July 22nd, 1895, the James Bay Railway Company was incorporated by Mackenzie and Mann to construct a line from Toronto to Parry Sound. For now, it would be isolated from their other railways in Manitoba which would adopt the better-known Canadian Northern Railway moniker in 1899. Soon afterward, after many years of avoiding the very possibility, the Grand Trunk began taking steps to construct its own transcontinental route to similarly rival Canadian Pacific. These factors influenced Canadian Pacific to resume their efforts to construct an independent Toronto to Sudbury line. In the words of one of Canadian Pacific’s reports for the fiscal year ending June 30th, 1904:

“In view of the contemplated construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, it will be impracticable to continue to use the Grand Trunk Company’s line between Toronto and North Bay for the routing of traffic between points in Ontario and points reached by [the Canadian Pacific] lines in North Western Canada, and, therefore it is important that you should, with the least possible delay, secure your own independent connection between the main line and the City of Toronto. The shortest and best route and one upon which the local traffic will be profitable, is from a point in the vicinity of Sudbury to a point near Kleinburg on your Ontario Division, a distance of about 230 miles”.

Survey work was once again conducted in 1901 and 1902, resulting in some slight changes from the previous surveys. The north end of the line would connect to the transcontinental line at Romford, located about 10 kilometers east of Sudbury. The southern end of the line was chosen to branch off the former Toronto, Grey & Bruce line at Bolton, just under seven kilometers west of Kleinburg. Construction at the north end of the line commenced in 1904, followed by work from the southern end in 1906. As part of these efforts, a significant amount of work was done to upgrade the former TG&B south of Bolton to the standards of a proper mainline and move it away from its narrow-gauge roots. Sharp curves and steep grades were eliminated by re-aligning segments of the railway near Emery, Woodbridge, Kleinburg, and Bolton. A large wooden trestle over the Humber River was replaced with a much larger steel one, capable of supporting the weight of the traffic that was expected once the line to Sudbury was finished. In an attempt to avoid further competition, the James Bay Railway took Canadian Pacific to the Supreme Court over their construction of the Toronto to Sudbury line, but the courts ruled in the CPR’s favour on April 6th, 1905. On June 15th, 1908, the Toronto to Sudbury line officially opened to rail traffic, almost in tandem with the competing James Bay line. Canadian Pacific ceased taking advantage of their trackage rights to North Bay on June 21st of that year.

Improvements for a New Century

The early 20th century was a time of vast infrastructure improvements for Canadian Pacific, both in the Toronto area and the rest of the CPR system. The single-track nature of most of the Canadian Pacific system in Ontario was becoming problematic as traffic increased. Directors of Canadian Pacific announced their intentions to double track their mainline between Montreal and Toronto on April 6th, 1898, and this plan was expanded further west soon afterward. Work began later in 1898, but it would take years before any progress on that front reached Toronto. One of the first indications that Canadian Pacific planned to vastly upgrade their facilities in the city occurred on January 30th, 1903, when it was reported that the company planned to replace their passenger stations at North Toronto and West Toronto. The latter had already seen a replacement in 1898, and efforts on these new replacements would not begin for another several years. Work began around the same time to double track a 6-kilometre segment from North Toronto to West Toronto Junction and further to Lambton, with this work being completed in the summer of 1905. As it turns out, this isolated section of double track would only be the beginning.

On September 30th, 1909, the Toronto World reported rumours of a planned Union Station to be built jointly by the Canadian Northern Railway and the Canadian Pacific Railway at Yonge Street, corroborated by what they described as “mysterious” property purchases in the area. Even though the two companies were fervent rivals, it is true that they were cooperating to establish a joint terminal away from the Grand Trunk’s Union Station. The original North Toronto station had become a convenient terminal for Toronto’s citizens, especially after a streetcar line was extended there up Yonge Street in 1885, but the 1884 structure would be rendered inadequate if it were shared with Canadian Northern. This location’s viability as a major terminal for Toronto was further tested by the introduction of new overnight passenger trains originating from North Toronto to Ottawa and Montreal on September 5th, 1910. Much of the reason for their introduction was as relief for Toronto’s overcrowded Union Station. The two companies avoided confirmations of their plans to the media until February 13th, 1911, when Canadian Pacific Railway vice-president David McNicoll presented the Toronto Board of Control with a list of improvements that his company had planned for its facilities in the city over the next several years. It not only included a new shared passenger terminal at North Toronto, but also a new viaduct to raise the tracks above the surrounding roads. However, while it was the goal of Mackenzie and Mann to vacate the Grand Trunk’s Union Station as soon as possible, it was made clear that Canadian Pacific still intended to remain in the downtown terminal. The Great Fire of 1904 opened up a significant amount of real estate to the immediate east of the existing Union Station, and Canadian Pacific agreed to build a joint passenger terminal on this site with the Grand Trunk on April 22nd, 1905. While construction of the station headhouse commenced relatively hastily, the railways and the City of Toronto would spend the next two decades deliberating over who would be responsible for grade separation of the rail corridor.

While efforts to lay double track between Montreal and Toronto was pushing west, surveys were done to determine where it was best to deviate the line to reduce the 1.1% grade west of Glen Tay. The result of these surveys was a greatly deviated line with a reduced grade of only 0.8%. It was eventually determined the optimal course of action would be to secure an entirely new right-of-way to the south of the original Ontario & Quebec line. Not only would this allow for reduced grades and smoother curves, but it would also provide Canadian Pacific with direct access to the larger towns along the shore of Lake Ontario which up to that point had been served exclusively by the Grand Trunk Railway. The Campbellford, Lake Ontario & Western Railway was chartered for this purpose on September 20th, 1904, and much like the Ontario & Quebec Railway it was to exist solely on paper as an extension of Canadian Pacific. In an unofficial capacity, most often in advertisements directed towards the public, the CLO&W was referred to as the “Lake Ontario Shore Line”. Construction stalled for several years, and the charter had to be extended by two years in 1906, again in 1908, and once more in 1910. Then, in the spring of that year, the Canadian Northern Railway began construction of their own line over a very similar route. David McNicoll confirmed in an interview in late 1911 that engineers were preparing for construction of the Lake Ontario Shore Line. The work began on May 1st of 1912.

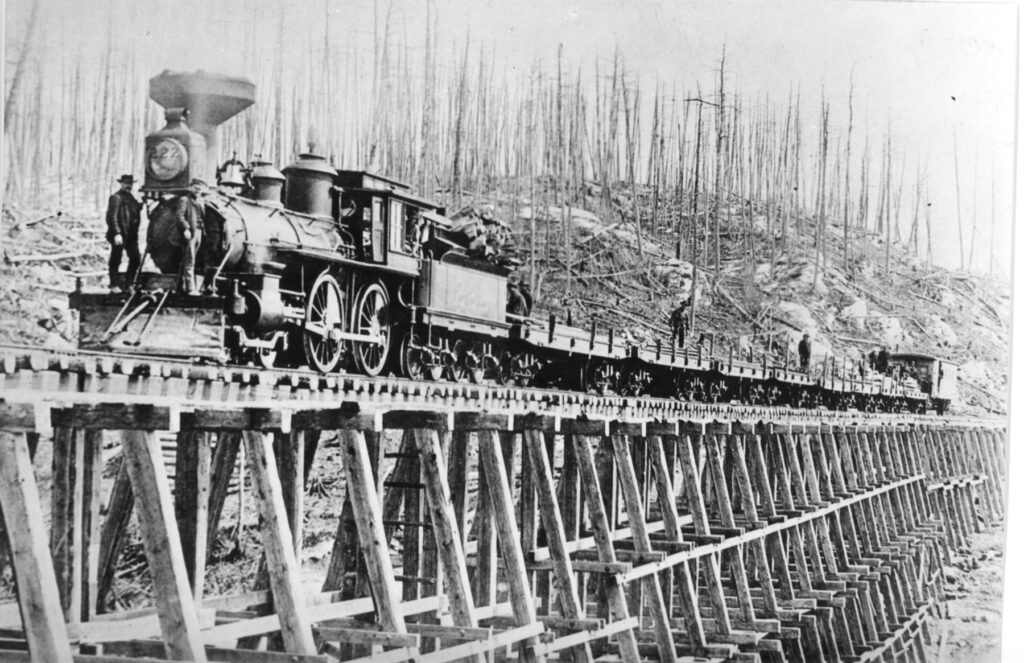

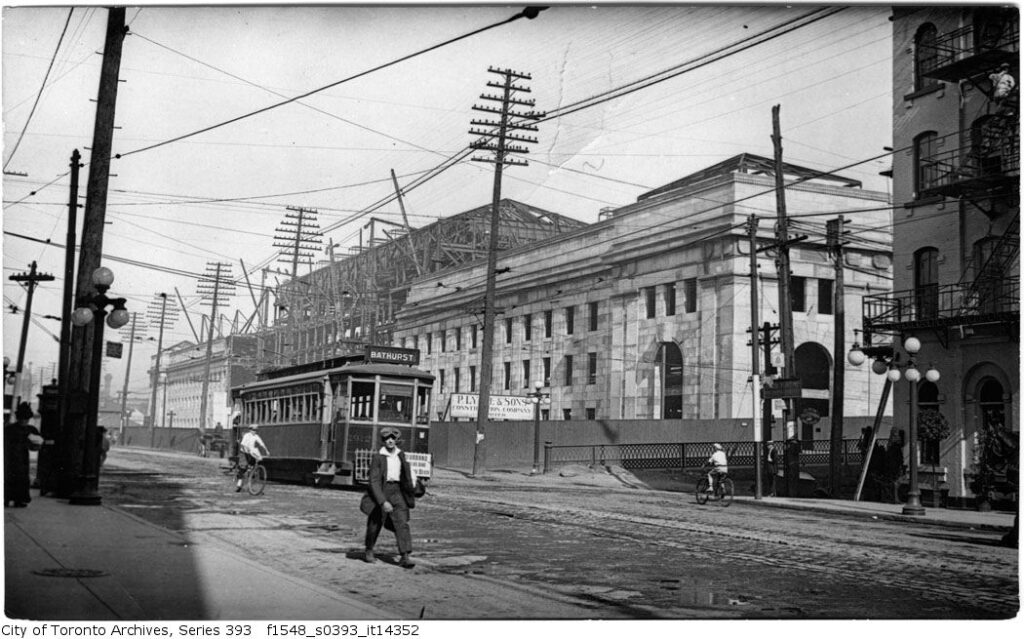

Simultaneously, a significant amount of work was being done in Toronto. A new 15-storey office building was to be built at the southeast corner of King Street and Yonge Street, where the company’s existing offices in the city would be consolidated. Attractive new passenger stations were built all over the Canadian Pacific system and the Toronto area was no different in this regard, with dozens receiving replacements during the first two decades of the 20th Century. In conjunction with a new shared North Toronto Station, the Canadian Pacific plans for a joint elevated rail corridor between Yonge Street and Dovercourt were approved by the Board of Railway Commissioners on June 25th, 1912. This corridor would be wide enough to accommodate both Canadian Pacific’s North Toronto Subdivision as well as a proposed Canadian Northern line to Niagara Falls. During the same year, work was completed on a new freight yard immediately west of the existing yards at West Toronto. Called Lambton after the nearby village of Lambton Mills, the new yard also contained a 30-stall concrete roundhouse with an 80-foot turntable. While the West Toronto Roundhouse’s smaller turntable was restricted to the smaller engines on Canadian Pacific’s roster, the Lambton Roundhouse was far more capable of handling steam locomotives of increasing size and weight. Just as the yard was completed the mainline adjacent to it was double tracked and work on replacing the single track bridge over the Humber River was done in 1914-1915. Construction of the new North Toronto Station commenced during the spring of 1913, followed soon after by the headhouse of the new downtown Union Station in 1914. The two buildings would follow the Beaux-Arts architecture style, though the two would be vastly different in their size and shape. The new Union Station would be the larger building by far, but one could argue the North Toronto station was the more visually striking building due to its conspicuous clock tower rising far above its surroundings. Double tracking was completed from Agincourt to Leaside on June 16th, 1914, followed by the opening of the Lake Ontario Shore Line on June 29th. Unfortunately, Canada made its entry into World War One just over a month later on August 4th. The war effort would require a significant amount of manpower and materials that would have otherwise been utilized by Canadian Pacific, significantly delaying, or sometimes cancelling numerous infrastructure projects across the system. The North Toronto station officially opened to passengers on June 14th, 1916, and the Union Station headhouse was effectively completed in 1920, though much work still needed to be done.

Interwar Years

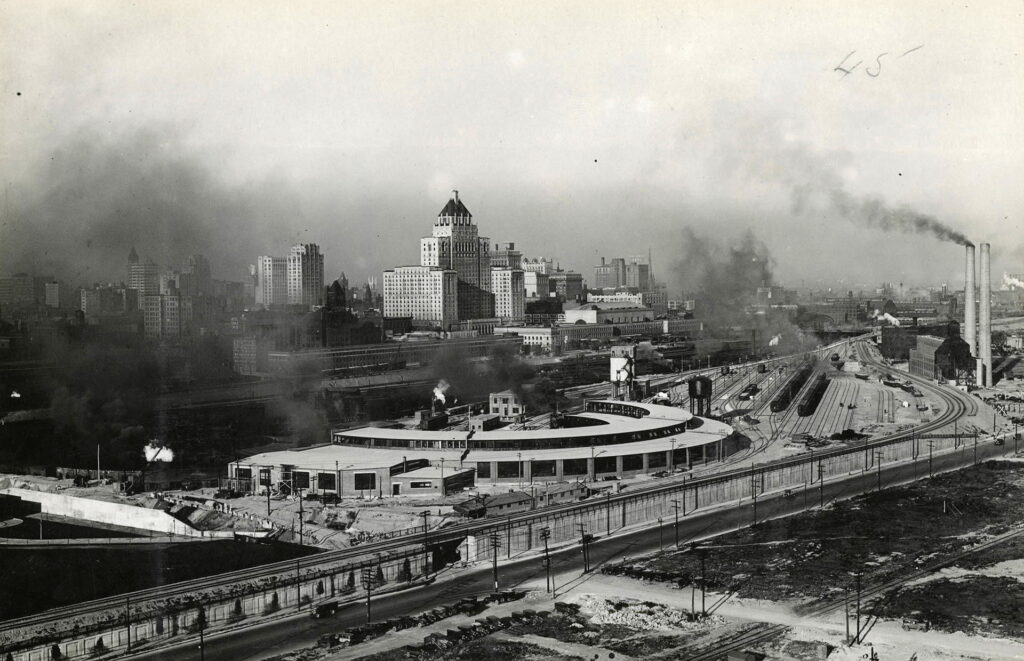

The Canadian Northern Railway would ultimately never serve North Toronto Station and its extension to Niagara would never be built, leaving Canadian Pacific as the station’s only inhabitant. Due to financial issues encountered by both of its rivals, Canadian Pacific now faced the federally managed Canadian National Railways as its primary competitor. This period saw a veritable arms race of new locomotives and equipment purchased by both companies as the two sought to attract more business. Trains such as the Trans-Canada Limited, itself having only been introduced in 1919, had its consist completely redone with all-steel passenger cars and new locomotives in 1923. As a result of the increasing size of these locomotives, the John Street Roundhouse’s 70-foot turntable had to be replaced with a larger one on two separate occasions. The first was an 80-foot turntable in 1911, followed by an 85-foot turntable in 1918. After it was decided in 1924 that the Union Station Rail Corridor would be raised above the surrounding roads, it presented an opportunity to modernize the John Street facilities even further. Over the next five years, the land surrounding the old John Street Roundhouse was gradually filled in to reach the elevation of the new corridor. A new roundhouse was built at John Street immediately south of its predecessor with the first 28 stalls officially opening on October 15th, 1929. The remaining four stalls were built once the original roundhouse could be demolished in 1931, and this also provided the space needed for numerous other adjacent facilities for tending to Canadian Pacific’s fleet of passenger equipment. The new roundhouse was officially known as the Toronto Locomotive and Car Facilities upon opening but unofficially retained the name of its predecessor. Its 120-foot turntable was easily one of the largest in Canada, and more than capable of handling the largest locomotives on Canadian Pacific’s roster. Unfortunately, the New York Stock Exchange would crash later the same month as the roundhouse’s opening, marking the beginning of the Great Depression. Plans for sixteen additional stalls were canned as the negative economic effects took hold. Numerous passenger services were reduced or cancelled altogether in subsequent years as passenger ridership dropped. North Toronto Station, which never saw anywhere close to the amount of traffic it was intended for, was closed to passengers on September 28th, 1930. It was easily one of the first Canadian Pacific projects to fall victim to the depression, but far from the last. On April 2nd, 1933, the Canadian Pacific Railway entered an agreement with Canadian National to pool both railroads’ passenger services between the cities of Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal. The result was a significant amount of CPR passenger traffic east of Toronto moving by way of the CNR.

World War Two, Dieselization, and Abandonments

The Second World War marked the end of the Great Depression and a rebound in passenger ridership for Canada’s railroads. The pool train agreement remained in effect for the time being, but new passenger services were introduced by Canadian Pacific to keep up with demand. The first diesel locomotives began to arrive on the CPR in Toronto towards the end of the war, starting with Canadian Pacific 7020 which arrived at the West Toronto yards in 1944. More dieselization would occur in the post-war era, during which numerous steam locomotives were reassigned or retired. In 1953, the Canadian Pacific Railway took delivery of numerous self-propelled Rail Diesel Cars from Philadelphia’s Budd Company. Two Budd RDCs made a trial run from Montreal to Toronto on October 24th, covering 340.5 miles in about six hours. They were parked at North Toronto Station where they were temporarily put on display for the public to view on October 29th. Their exterior was made of fluted stainless steel which had been a trend in the United States’ passenger rail industry for decades but had yet to make as much of an impact in Canada. Cab unit diesels such as General Motors’ F-series and others were also making appearances in Toronto, first on road freight trains and then passenger. The overnight Toronto-Montreal trains 21 and 22 were dieselized on March 11th, 1954, resulting in the reassignment of steam locomotives 3100 and 3101 to Quebec. Canadian Pacific introduced their new flagship transcontinental train, The Canadian, on April 24th, 1955. Much like the Budd RDCs, this train used sets of fluted stainless-steel passenger cars manufactured by the Budd Company. The engines used on this train were regularly maintained at the John Street Roundhouse, initially utilizing a pair of General Motors FP7s. The reactivation of West Toronto as a maintenance facility for diesels rendered the Lambton Roundhouse obsolete once steam engines were retired, and the latter was demolished in late 1960. Roundhouses were gradually phased out in the decades following the end of steam, but the removal of the Lambton Roundhouse was easily the first in Toronto that could be directly attributed to the mass adoption of diesel locomotives.

While dieselization was occurring, the railway industry in Canada would face similar issues encountered during the Depression but for much different reasons. According to Statistics Canada, passenger rail ridership saw a 56% drop country-wide between 1946 and 1961. Much of this could be attributed to increased automobile production immediately following the end of World War Two, alongside the rapid construction of automobile-related infrastructure incentivizing people to drive over taking the train. The heightened popularity of air travel was also a factor, particularly over longer distances. Highway 7’s eastern segment, which was built between 1930 and 1932 as a Depression-era relief project, mirrored the route of the Ontario & Quebec line between Peterborough and Perth. It also served many of the same major communities as the railway. After the war, divided highways such as Highway 401 would also compete directly with existing rail infrastructure. The passenger services most affected by the popularization of automobiles were often branch lines, which were rarely profitable even before the invention of the car. As a result, the relatively low running costs of Budd RDCs made them an obvious choice for many regional, commuter, and branch line passenger services. Canadian Pacific first put them in service on a Toronto to London run in November of 1953, and extended further to Windsor soon after. RDCs were utilized between Toronto and Peterborough in September of 1954, and service was similarly extended further to Havelock in 1957. They also saw use on the Bruce Division’s vast network of branch lines, namely between Toronto and Owen Sound. By the late 1960’s, Budd RDCs made up the backbone of Canadian Pacific’s remaining short-haul passenger service. However, they were not immune to poor ridership. On October 24th, 1964, the Board of Transport Commissioners ordered Canadian Pacific to continue passenger service between Toronto, Peterborough, and Havelock, to support the commuters who relied on it despite its lack of patronage.

The postwar era also saw massive changes in Canadian Pacific’s Toronto-area freight facilities. The John Street yards were expanded to include trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) facilities in 1952, an early predecessor of modern intermodal containers. Perhaps the largest development was the opening of Canadian Pacific’s Toronto Yard on April 26th, 1964. Despite the name, this massive freight yard was built over 20 kilometers away from the city in what was then a rural area of northern Scarborough. The yard was strategically located inside the junction of the 1914 Lakeshore Line and the 1884 Ontario & Quebec line. Operations were gradually moved there from the other smaller yards scattered around Toronto in subsequent years, excluding Lambton which remains in use today. The pool train agreement ended on October 31st, 1965, and Canadian Pacific began offering their own passenger service between Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal for a brief time. A new westbound train called the Royal York and its eastbound counterpart the Chateau Champlain were introduced between Toronto and Montreal, each one named after Canadian Pacific hotels in their respective destinations. These trains used stainless steel Budd cars and were essentially pocket versions of The Canadian. Unfortunately, they were unable to compete with Canadian National’s faster and more affordable Rapido service, and both the Royal York and Chateau Champlain ceased further operations just a few months later on January 23rd, 1966.

Perhaps the clearest sign of Canadian Pacific’s shift away from the passenger business was the closure and demolition of passenger stations in the Greater Toronto Area over the next two decades. For the vast majority of communities this was the end; no replacement would ever come. For stations of particular architectural or historical interest, preservation efforts often could not be mounted in time by local community members. For the Toronto area, this also applied to many bedroom communities that were rapidly suburbanizing in the postwar era. GO Transit was formed by the province of Ontario in 1967 to ensure some commuter service remained for the City of Toronto and its environs, but it initially remained on tracks owned by Canadian National. Canadian Pacific, the only private company of the two big railways in Canada at the time, was generally more resistant to introducing government-run passenger traffic on its lines. It wasn’t until after the Mississauga Miracle – the 1979 derailment of a train carrying dangerous goods and the subsequent evacuations, that this would change. Instead of facing a lawsuit by Mississauga, GO Transit was permitted on the Canadian Pacific right-of-way west of Toronto and the Milton Line was opened two years later. The remainder of Canadian Pacific’s passenger service in Toronto had already been assumed by VIA Rail on October 29th, 1978, after its formation one year earlier.

Canadian Pacific in Toronto Today

The next several decades up to the present could generally be defined by Canadian Pacific’s gradual withdrawal from downtown as more operations were consolidated at Toronto Yard. The freight facilities at King Street and Simcoe Street were closed between 1977 and 1985, resulting in their demolition soon afterward. The last local freight movement departed Parkdale Yard on March 16th, 1986, ending over a century of railway activities on that site. The West Toronto Roundhouse had similarly managed to survive over the same length of time but was sadly demolished in May of 1998. Operations in the vicinity of downtown Toronto finally ended with their 2007 withdrawal from the industries they served in Ashbridges Bay. Canadian Pacific’s annual Holiday Train made use of the Don Branch one final time in December of 2007. It remains in a derelict state to this day, though the branch was sold to Metrolinx in 2009 presumably for future commuter rail operations. After the John Street Roundhouse was donated to the city in 1986, the Toronto Railway Museum officially opened there in 2010. The roundhouse itself and several pieces in the museum’s collection represent some of the only remaining pieces of Canadian Pacific’s presence in downtown Toronto. On March 21st, 2021, Canadian Pacific declared its intentions to acquire the Kansas City Southern Railroad. This became a reality on April 14th, 2023, and the company was renamed to Canadian Pacific Kansas City Limited. This represents one of the largest changes in the company’s branding since its inception.

Written by Adam Peltenburg

References

Boles, Derek. 2009. Toronto’s Railway Heritage. Arcadia Publishing.

An Act to Incorporate the Ontario & Quebec Railway. 1871. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_04329/3

Young, Brian J., and Gerald J. Tulchinsky. 1982. “Biography – ALLAN, Sir HUGH – Volume XI (1881-1890) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/allan_hugh_11E.html.

Keefer, George A. 1872. Report on the Preliminary Examination of the Ontario & Quebec Railway. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.23781/9.

An act respecting the Canadian Pacific Railway. 1881. N.p.: Brown Chamberlin. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.02074/6.

An Act to incorporate the Ontario & Quebec Railway Company. 1881. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08051_10_2/40.

The Toronto World. 1883. “The West Toronto Junction Cheap Lands.” April 14, 1883. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18830414/4.

The Toronto Weekly Mail. 1884. “Railway News.” January 3, 1884, 10. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00173_18840103/2.

The Toronto World. 1884. “The Kaladar Sink-Hole.” July 11, 1884, 4. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18840711/1.

The Toronto World. 1884. “C.P.R.’s New Quarters.” May 10, 1884. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18840510/1.

The Viaduct, Esplanade and Don Improvement Questions, Letter from the President of the Canadian Pacific Railway Co. to the Mayor of Toronto. 1890. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.25309/12.

The Toronto World. 1885. “Opening of the Canadian all Rail Route to Winnipeg and the Rocky Mountains.” November 3, 1885. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18851103/3.

Weekly Monitor. 1886. “General News.” June 30, 1886. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00693_18860630/3.

Sproat, C. 1889. Statutes, by-laws and documents connected with the straightening and improvement of the River Don. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.89416/105.

The Toronto World. 1888. “East Toronto Junction And Rosedale.” November 24, 1888. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18881124/5.

The Toronto World. 1891. “The Coming Year in Railroading.” January 7, 1891. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18910107/2.

“In the High Court of Justice.” 1899. In Union Station Agreement. Toronto: Warwick & Rutter. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.08928/9.

The Toronto World. 1897. “Railway Notes.” August 28, 1897, 12. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18970828/10.

The Toronto World. 1898. “Toronto-To-Sudbury Line Being Surveyed.” March 16, 1898. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18980316/1.

The Chronicle. 1898. “The Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s Meeting.” April 8, 1898. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_04460_5/7.

The Semi-Weekly Colonist. 1903. January 30, 1903. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00333_19030130/7.

Lovett, Henry A. 1981. Canada And The Grand Trunk, 1829-1924. New York City, New York: Arno Press.

Parsons, W. B., C. B. Smith, and C. H. Rust. 1907. Report of Engineers, Report of engineers on the separation of grades in connection with the railway lines along the water front and on the proposed Union Station. Toronto, Ontario: n.p. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.84023/9.

The Toronto World. 1909. “Railway Move to North End Coming.” September 30, 1909. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19090930/1.

The Toronto World. 1910. “All Aboard, North Toronto.” September 2, 1910. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19100902/9.

The Toronto World. 1911. “C.P.R. Plans To Spend $7,000,000 In Toronto.” February 14, 1911. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19110214/9.

The Toronto World. 1912. “C.P.R. Passenger Business To Be Concentrated Uptown.” June 27, 1912. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19120627/1.

“Pool Trains: A Pictorial Study of the Toronto-Montreal and Toronto-Ottawa Pooled Passenger Train Services.” n.d. Upper Canada Railway Society Bulletin, no. 52. https://bzglfiles.s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/u/131959/13b9f6092e6563d49b1309b7fe3582975c19d105/original/ucrs-bulletin-52-435.pdf?response-content-type=application%2Fpdf&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA2AEJH4L527DJJBYE%2F20230321%2F.