Introduction

Few railway companies in Canadian history could compare to the Grand Trunk Railway in size or influence. It was the second railway to arrive in Toronto – beaten to the title of first by only two years. Through a vast amount of investment from business interests in England it was able to expand rapidly across what is now the Province of Ontario, connecting our largest cities with the eastern and midwestern United States. By the year of Canada’s confederation in 1867, fourteen years before the arguably more famous Canadian Pacific Railway had even been chartered, the Grand Trunk Railway achieved the title of the longest railway system in the world at 2,055 km (1,277 mi) of track. The effects of this railway’s actions within Toronto – good and bad – have outlasted the railway company itself in many cases. If you’ve ever lived in or visited Toronto, you may notice this railway’s name is one of three engraved on the front façade of Union Station. Although it was heavily involved in the station’s construction, the company did not survive long enough to see its opening in 1927. The loss of an important leadership figure and the construction of an ill-advised extension to the west coast are widely attributed to the railway’s financial troubles during and after World War One. Despite succumbing to these problems shortly after the war, the former Grand Trunk system continues to form a significant portion of Canadian National’s most important rail corridors in eastern Canada and parts of the United States. Numerous structures and pieces of equipment that originated with the Grand Trunk can still be found in many places today.

The Great International Route

In the decades following the War of 1812, Canada had largely fallen behind its British and American counterparts in the development of its railways. Many attempts were made but often failed due to financial uncertainty. By the middle of the century a handful of small railway companies had begun operating, but intercity routes were essentially restricted to roads and waterways which would often become impassible during the winter months. Between Montreal and Toronto, which were then Canada’s first and third largest cities respectively, Kingston Road was built in segments throughout the early 1800’s and became a major stagecoach route by 1817. However, poor maintenance and the introduction of tolls in the 1830’s helped motivate local efforts to improve travel between the two cities.

While the Grand Trunk Railway has its roots primarily along the north shore of Lake Ontario, much of its early history can be traced to Portland, Maine. The American city had an ice-free port on the Atlantic that presented a significant opportunity for commerce in Montreal. However, business interests in Portland sought to eliminate the possibility of competition from Boston to the south. When the Atlantic & St. Lawrence Railroad was chartered in 1845, it was planned to be built with a 5-foot 6-inch gauge. This differed from the 4-foot 8.5-inch gauge which had become ubiquitous in most of the other parts of the United States, with the goal of giving Portland its edge over Boston. As such, it was colloquially referred to as “Portland gauge”. On the Canadian side of the border, a separate charter for the St. Lawrence & Atlantic Railway was used for the remaining section to Montreal. Construction of both railways commenced in 1846, but financial issues delayed their completion. When they were eventually completed, they became the first international railway on the North American continent.

Simultaneously, the Canadian government sought to financially incentivize the construction of more railway lines in Canada. The Railway Guarantee Act was passed by the Province of Canada in 1849, ensuring that interest on half of a given railway’s bonds were eligible for a guarantee from the government once half of the railway line was complete. Eligibility was also determined by the length of the railway, which had to be at least 120 kilometers (75 miles) long. A Board of Railway Commissioners was formed in 1851 to administer the guarantee, and the following year they would add a controversial condition to it. The committee was made up of ten individuals, all of whom were involved in the railway industry and included executives of existing Canadian and American railroads. A majority of the committee were initially in favour of the 4-foot 8.5-inch “standard” gauge as a requirement for the guarantee, with six for, three against, and one abstain. These were dramatically altered once the pros and cons of each gauge were weighed by the committee. The St. Lawrence & Atlantic’s Vice President John Young, a member of the committee, had a vested interest in the Portland gauge since construction of his railway was well underway at this point. British trading companies also stood to benefit if the Portland gauge was incentivized by restricting competing trade with the United States. From a national security standpoint, the gauge disparity would theoretically hinder attempts to invade Canada by slowing down troop trains. This must have been at least a matter of some consideration given the last war with the United States had occurred just four decades earlier. In any case, the final decision was nine to one in favour of the Portland gauge which from then on was referred to as “provincial gauge” in Canada.

The Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada was incorporated on November 10th, 1852, for the purpose of constructing a railway between Montreal and Toronto. It chose to adopt the provincial gauge both to take advantage of the loan interest guarantee, as well as match the railway companies it planned to gain control of. On August 5th, 1853, the St. Lawrence and Atlantic and its parent company the Atlantic & St. Lawrence were effectively merged into the Grand Trunk just several months after they had begun regular service.

The Western Division

The Grand Trunk Railway’s entry into Toronto began with an independent venture that sprung up long before its formation. In 1847, the Toronto & Goderich Railway Company was chartered by lawyer and railway promoter John W. Gwynn. The government refused to provide the necessary subsidies to get the company off the ground and it was re-chartered in 1851 as the Toronto & Guelph Railway. The new plan would cover a far more achievable distance than its predecessor, and the precise route it would take was decided the following year in June 1852. It was to start near downtown Toronto and pass through the communities of Weston, Brampton, Georgetown, Acton and Rockwood on its way to Guelph. It was initially estimated to cost 250,000 pounds at the time, equivalent to about $60 million in Canadian dollars when adjusted for inflation. However, this sum did not include the cost of rolling stock or the right-of-way, so the total cost would have certainly been greater. Despite this, an article dated June 3rd, 1852 from the Guelph Advertiser states: “…the general talk among many influential Torontonians is, that they will have the Road, cost what it will”. The hope was that the railway would pay for itself in due course, as another excerpt from the Guelph Advertiser points out:

“The country through which this Railway will pass, is not surpassed in fertility of soil, or capability of production, by any other section of equal extent in Canada; and the traffic which may reasonably be anticipated upon it, cannot fail to be highly remunerative to all Stockholders,”.

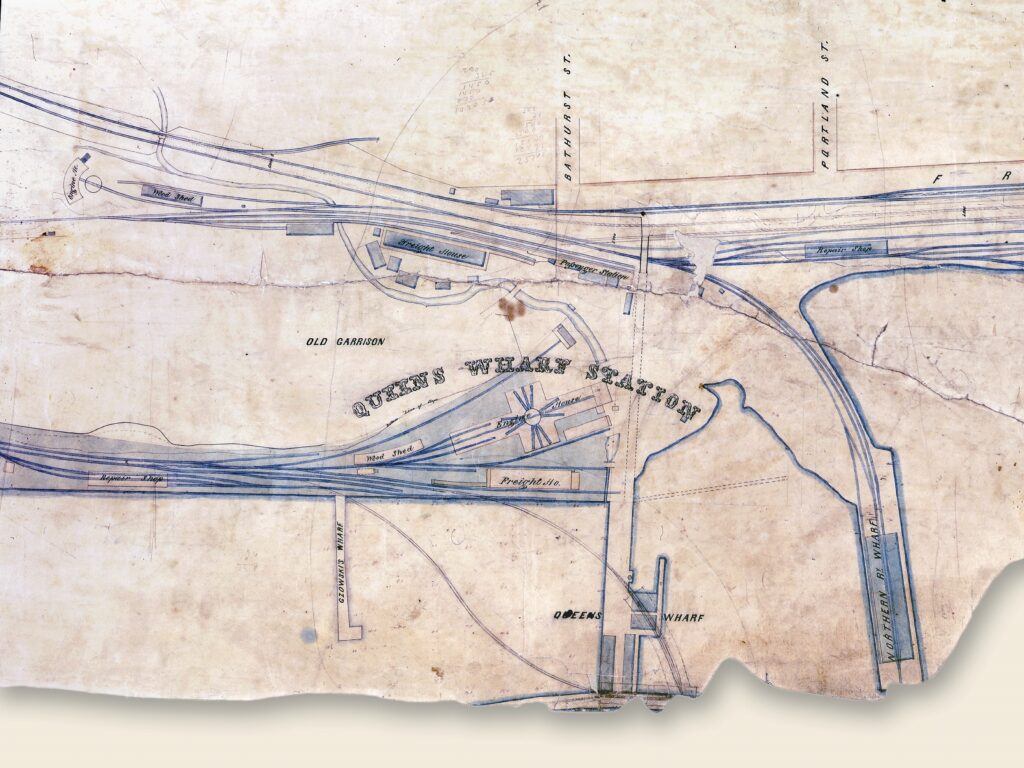

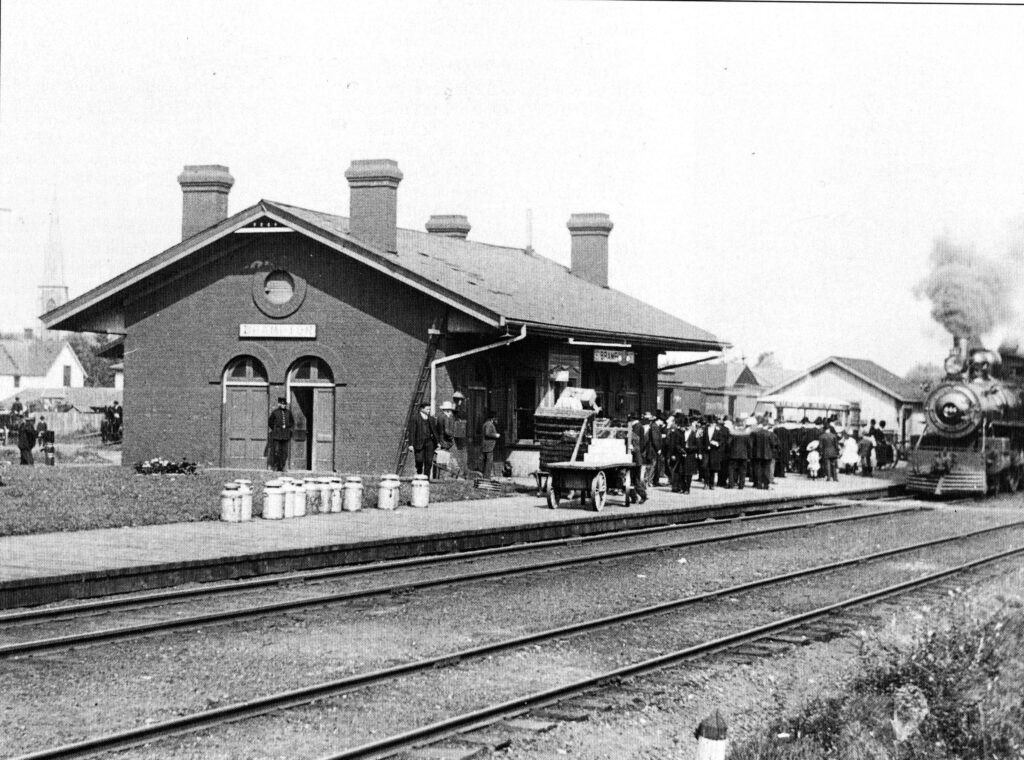

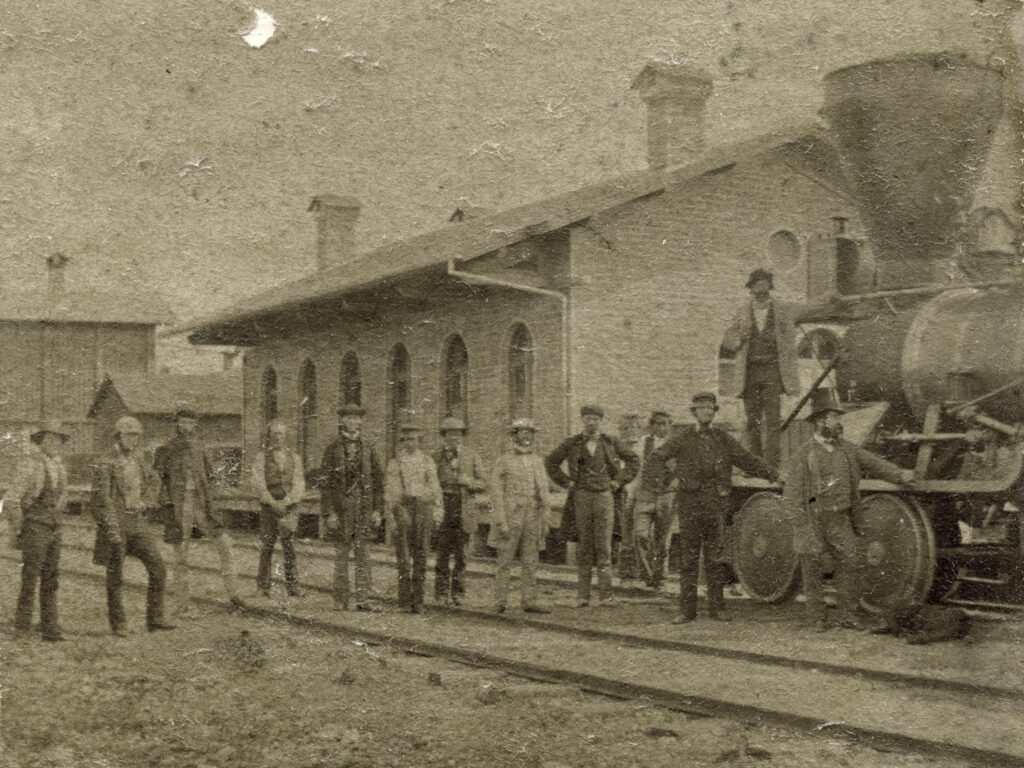

Shortly after the Grand Trunk Railway was chartered, it was amended to include a far more ambitious route in both directions. While the St. Lawrence and Atlantic would give immediate access to Portland, the Toronto & Guelph Railway would be acquired by the Grand Trunk in 1854 to use as a stepping stone to reach Sarnia. Construction of the line from Toronto to Sarnia was contracted to Casimir Gzowski, a Polish-Canadian engineer who had decades of experience with railways and public works projects. In May 1854, it was estimated that 10,000 workers were actively participating in the Grand Trunk Railway’s construction. Over 570,000 pounds had already been spent on the Toronto-Sarnia section alone by November of that year, and the total price of the contract was more than double that amount. Despite the steep cost, a significant amount of progress was seen on that stretch within the first year, attributed to an unusually mild weather pattern. The railway’s eastern terminus in Toronto, which included a cruciform enginehouse, a freight house, and a small stub-ended passenger station, was built at Queens Wharf along the southern edge of Fort York. These facilities were all built on new fill in the Toronto harbour just west of the wharf, which is where several of the Grand Trunk’s early locomotives and rolling stock arrived by boat. Several early engines were also built locally by James Good’s Toronto Locomotive Works. This manufacturer was responsible for the production of at least one Grand Trunk locomotive as early as 1854, only a year after it produced the first locomotive ever made in Canada for the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway. In a reply to the Committee on Railroads, Canals and Telegraph Lines, Sir Cusack Roney, Managing Director of the Grand Trunk optimistically estimated that the first 90 miles from Toronto to Stratford would be opened for traffic by October 1st, 1855. The date was not far off of reality, but the distance would be. The construction of a bridge over the Credit River west of Brampton was responsible for delaying the official opening beyond that point. On October 18th, 1855, the Grand Trunk operated their first train from Toronto to Brampton, a distance of only 21 miles. This made it the first segment of the Grand Trunk Railway to open for traffic on this side of Montreal and made the Grand Trunk the second railway to reach Toronto. The section of the Grand Trunk west of Toronto would originally be referred to as its “western division”, and according to the London Morning Chronicle it became the most profitable segment of the Grand Trunk within its first year of operation.

The Central Division

While the Grand Trunk Railway was to exist primarily within the Province of Canada, it was very much a British railroad in terms of its management and financial backing. This is reflected in the steps the company took to align itself with other railway companies across the pond and to stand out from American railroad companies. In the same reply made to the Committee on Railroads, Canals and Telegraph Lines mentioned earlier, Sir Cusack Roney plainly stated these intentions:

“The line and all its appurtenances shall be equal to any first-class English Railway, and superior to any now known or used on this continent. The bridges are to be of masonry or brick work with iron tubes across the spans. All these tubes are on the principle of the well-known Brittania Bridge across the Menai Strait in Wales. The stations and all other buildings, such as engine repairing shops, etc., are to be of brick or stone covered with slate or metal”.

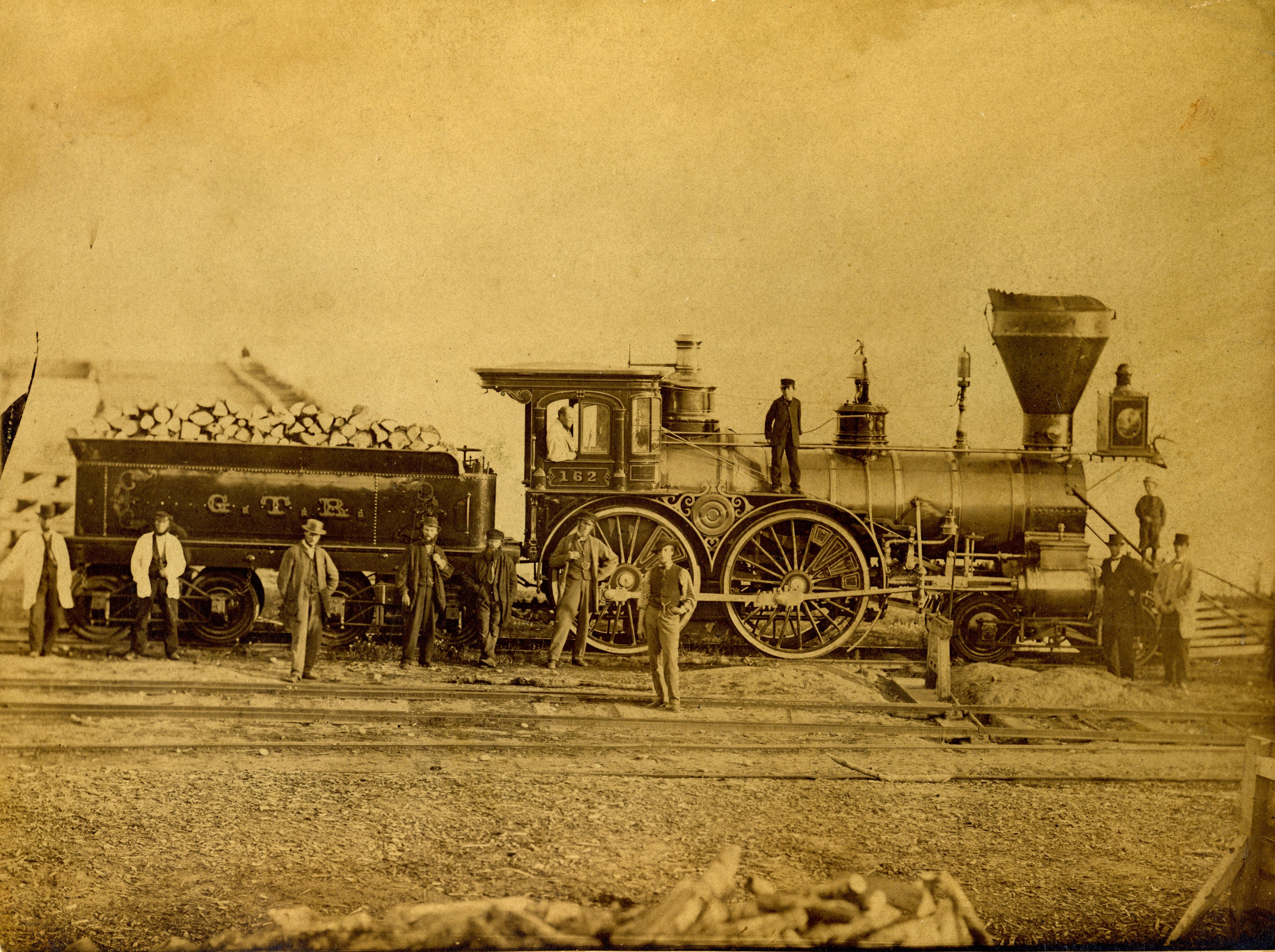

The Grand Trunk’s British influence was perhaps most obvious on its Toronto-Montreal line, or “central division”. The contract for its construction was awarded to the firm of Peto, Jackson, Brassey and Betts on December 14th, 1852, for the price of 3 million pounds. The individuals in charge of this firm were all Englishmen who were heavily involved in the construction of railways in Europe. Not only would they be responsible for the construction of the railway itself, but the bridge spans, iron rails, and numerous locomotives would be shipped overseas from Thomas Brassey’s Canada Works in Birkenhead, England. The first of the Birkenhead locomotives to be delivered, a passenger engine with a 2-4-0 wheel arrangement, arrived in November 1854. Though it only bore the number 41 on its exterior, it is said that this locomotive was named Lady Elgin after the wife of the Governor General of Canada, James Bruce. In typical English fashion, the engineer’s seats of the Birkenhead locomotives were located on the left side of the cab. While the concept of a double-track railway would not exist in Canada for another two decades, the Grand Trunk would maintain a policy of left-hand running wherever double track existed throughout the rest of the 19th Century. A total of fifty Birkenhead locomotives were delivered to the Grand Trunk between 1854 and 1858, all of which gained reputations as some of their most durable engines. Some remained in service on the Grand Trunk into the 1880’s while others were later sold to the Carillon and Grenville Railway where they earned their keep into the early 1900’s.

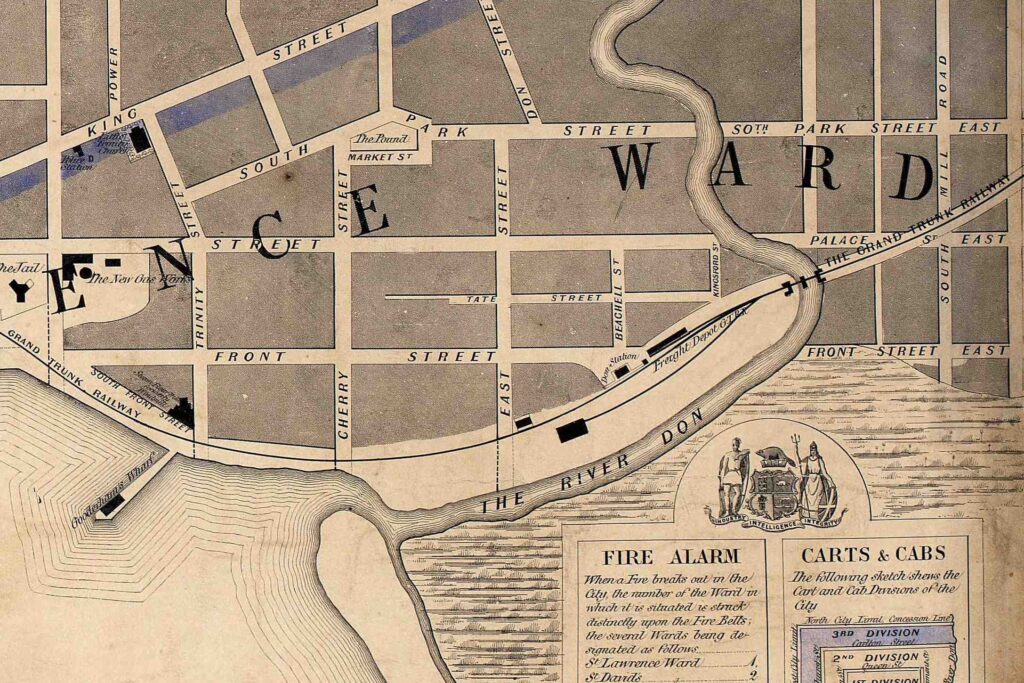

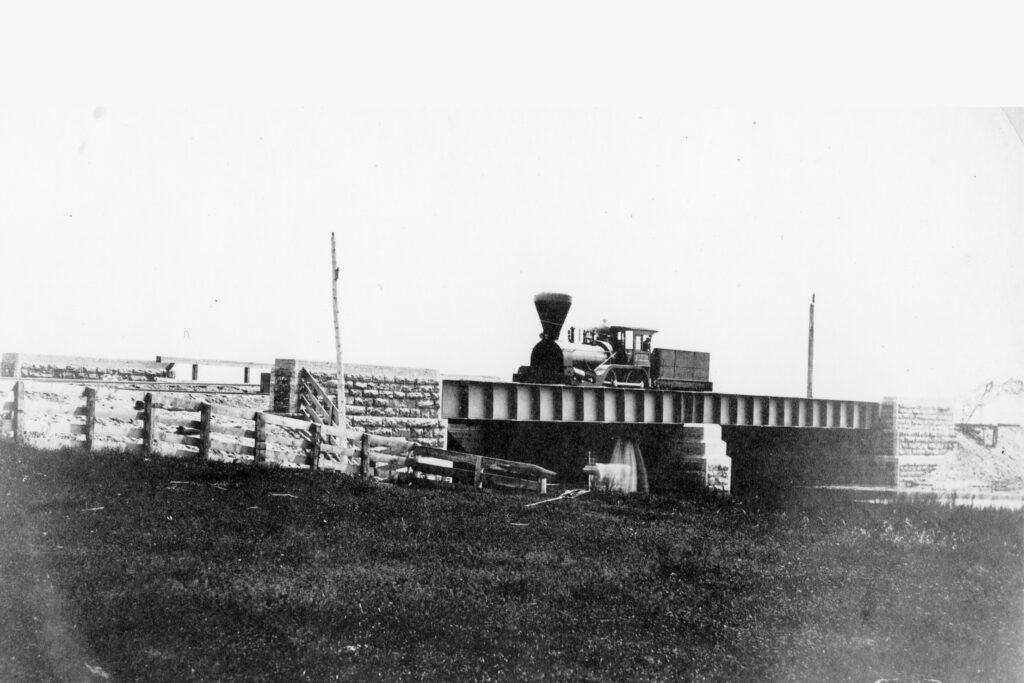

Construction of the Grand Trunk’s central division began in stride shortly after the contract was amended in 1853, and the first ground was broken ten kilometres (six miles) east of Kingston on January 10th, 1854. After the land for a given segment of the right-of-way was purchased a group of workmen would push forward with the railway bed. The first locomotives on this section were only used to aid in its construction at this point in time. The relatively flat terrain along the north side of the St. Lawrence River allowed the work to progress much faster than other sections. The Grand Trunk officially opened the first segment of its central division from Montreal to Brockville on November 19th, 1855, a month after the western division. Other sections of the railway proved much more difficult to conquer. As construction began eastward out of Toronto the Grand Trunk’s steepest grade thus far would be encountered no more than a few kilometres after crossing the Don River. Later known as the Danforth Hill, the grade would climb to a point just north of the Scarborough Bluffs. From there it would descend to Port Union before leveling off again. The Grand Trunk’s first train east from Toronto departed a small station just east of Cherry Street on August 11th, 1856, bringing ten passenger cars to Oshawa before returning. This passenger move was treated as a special excursion and it did not mark the beginning of regular service, which wouldn’t begin for over a month. Press officials who were invited onto the train reported large crowds of people watching the excursion pass at each settlement along the line.

Whilst the construction around Toronto was completed that summer, contractors were hard at work building the remainder of the line between Brockville and Oshawa. A particularly difficult section was encountered between Bowmanville and Brighton where more hills were present in the terrain. At Port Hope the Grand Trunk needed to cross the mouth of the Ganaraska River – its widest point. The resulting bridge would be the longest on the central division by far, and briefly the longest on the entire Grand Trunk system until the completion of Montreal’s Victoria Bridge in 1859. Named the Albert Bridge after Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert, it reportedly measured 1,856 feet in length and was held up by 56 piers. It took until October 13th, 1856 for the first test locomotive to cross it, which significantly delayed the commencement of regular service on the central division. On October 27th, the first regular passenger trains departed from Toronto and Montreal almost simultaneously. The two trains met at Kingston Station where a brief ceremony was held before they continued on their way. These express trains offered by the Grand Trunk sped up travel between the two cities to fourteen hours – a convenient alternative when such a trip took five days before the railway’s arrival. Local service was also offered stopping at every station on their route, though usually only traversing a small part of the line at either end. The central division’s opening also made winter travel far more viable. While competition from shipping on Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence during the summer months would impact its profitability, the Grand Trunk would have a monopoly over freight movements for almost half the year.

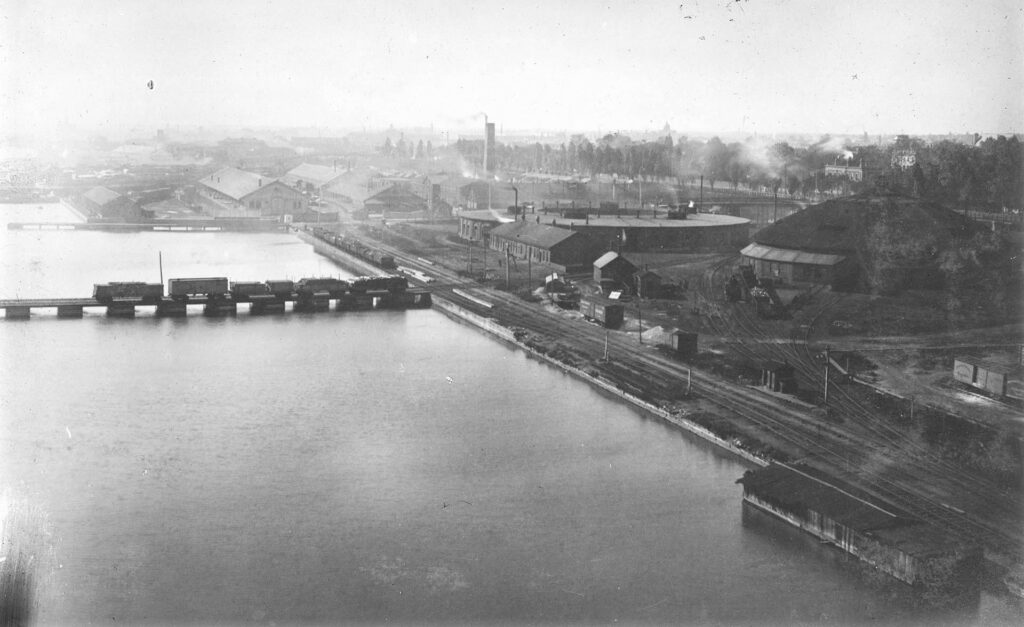

Crossing the Esplanade

Upon the opening of the Grand Trunk’s western and central divisions in 1855 and 1856 respectively, both were separated by a distance of about 3.5 kilometres (2.2 miles) in Toronto. The reason for this was that the harbour had become crowded with industrial buildings which rendered it impassable. The only alternative for the Grand Trunk would have been moving their right-of-way to the undeveloped areas north of the city and risk losing out on lucrative freight and passenger business in doing so. Determined to join both divisions across the waterfront, officials of the Grand Trunk opted instead to influence local politics to get their way. Luckily for them a planned beautification project would be just the ticket. In an effort to create a more inviting space on Toronto’s waterfront, city officials had been consulting with numerous architects since the early 1850’s. The plan settled on by the city was a road measuring 100 feet in width along the shore called an Esplanade. On January 21st, 1856, the Grand Trunk Railway entered an agreement with the City of Toronto to underwrite the infilling of the harbour for this project. In return, the Grand Trunk would be granted a 40-foot strip down the middle of the Esplanade to lay their tracks. This decision, considered by Toronto architect Frederick Cumberland to be “unwise in the last degree, and justified by neither common sense nor professional opinion”, would separate Toronto’s citizens from their waterfront for over a century to come. Thus began a tenuous relationship between the Grand Trunk and the residents of Toronto who would begin to harbour an unfavourable opinion of the railway.

In the meantime, a horse-drawn omnibus service was offered to ferry passengers between both divisions in the Esplanade’s absence. After the central division’s opening, new locomotives were also brought to the western division by rail, but to cross the gap had to be moved along the city’s streets by laying temporary rails relay-style while manually pushing the locomotive forward with pinch bars. By February 12th, 1857, temporary tracks were laid along the north side of the Esplanade while it was still under construction to provide through service in the interim. A temporary passenger station was also built at Bay Street, described as “a rude and temporary shed” by the railway’s General Manager and Engineer Walter Shanly. Plans for a permanent station for Toronto were drawn up as early as 1855, having a sturdy and attractive design worthy of the city. Unfortunately for the Grand Trunk and Torontonians, the Panic of 1857 and the ensuing economic crisis ensured this station would never be built.

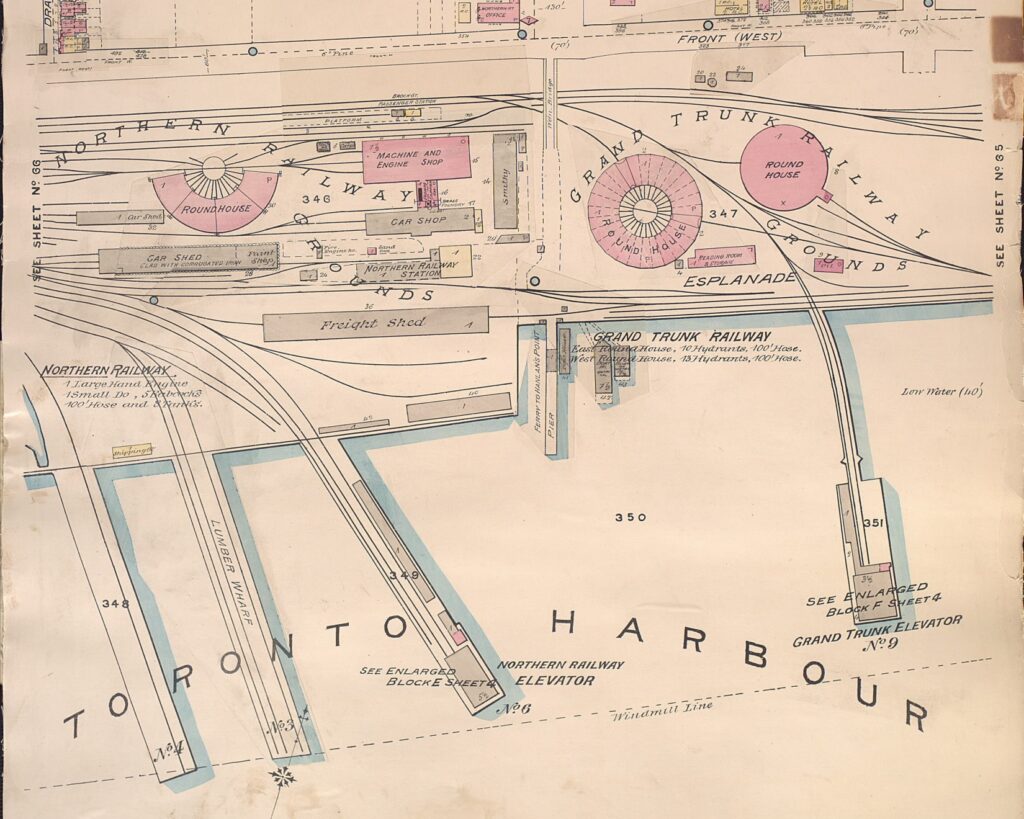

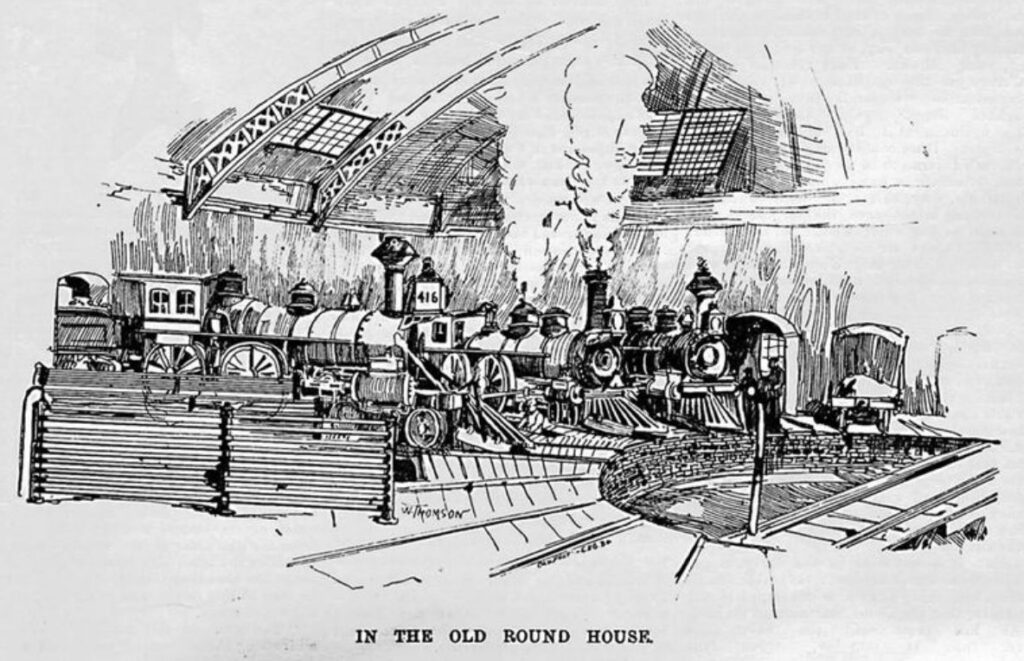

Over the course of the next year, a significantly toned-down permanent station was built by the Grand Trunk instead. Located at York Street, the new station would have an unsheltered platform and its headhouse was made almost entirely from wood. A new locomotive storage and maintenance facility was also built at Spadina Avenue in tandem with the station, taking the form of a dome-covered roundhouse resembling many others in Europe and some in the eastern United States. An agreement was reached with the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway and the Great Western Railway to share the new station as a joint passenger terminal or “union station”. The first trains began arriving at the Union Station on June 21st, 1858. In speaking about the new station in a poorly aged quote, Shanly said of it: “…though not of large proportions or of very expensive character, [Union Station] is sufficiently commodious to be likely to answer our purpose for several years to come”. While the new roundhouse replaced the older locomotive facilities at the Don River, the locomotive maintenance and freight facilities at Queens Wharf would remain in use to handle traffic from the west. By 1857, the Grand Trunk had a total of 849 miles of track in operation and rostered a fleet of 197 locomotives.

Westward Expansion & Money Problems

The Panic of 1857 took a broader toll on the Grand Trunk, resulting in a “considerable falling off” in traffic according to Shanly’s 1858 report to the company directors. The report goes on to say that the Grand Trunk’s passenger service saw the most losses while freight revenue saw a slight increase over the same period. The day express trains between Toronto and Montreal were briefly discontinued at times for the more profitable night express, which had made its inaugural run on March 23rd, 1857. As a result of the depression, very little expansion occurred besides the mainline during the latter half of the decade. The western division was extended to St. Marys by September 27th, 1858, and it took until November 21st, 1859 for the railway to reach Point Edward just north of Sarnia. Despite the Grand Trunk’s financial position, a large building with flashy architecture was constructed at the latter location to serve as a passenger station, hotel, and ferry terminal.

The Grand Trunk didn’t fare much better after the depression ended, due in part to the onset of the American Civil War in 1861. However, the greater cause of its poor performance was the degrading condition of its existing rolling stock, and an overall shortage of the necessary equipment once traffic began to rebound in 1860. An 1861 report from a commission inquiring into the affairs of the Grand Trunk spoke of dire circumstances:

“In spite of the improvement in the traffic during the past year, it is evident, that a much larger profit must be realized, than any that has hitherto been reached, if we are to entertain hopes of the road being self-sustaining”.

A total of 46 of the Grand Trunk’s locomotives were found to have been built too light to handle Canada’s harsh winters, which certainly would have contributed to the equipment shortage. By 1858 the malleable iron rails were already in need of replacement, owing in part to increased rail traffic. Cost-cutting measures were taken in the years that followed to ensure profits were kept at a sustainable level. The replacement of rails along the Esplanade was deferred to the spring of 1860. For 18 months from 1862 onward, maintenance of rail cars was “almost at a standstill” and some had sat unusable in railyards for up to two years. Despite these conditions the Grand Trunk’s president Edward Watkin became interested in the possibility of establishing a transcontinental railway under his company, making use of a steamship service across the Great Lakes to do so. The concept became far more viable when the provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick were united into the Dominion of Canada on July 1st, 1867. Although the Grand Trunk’s financial condition was now improving, Watkin was in the minority when it came to his position on expanding the Grand Trunk to the west coast. He was forcibly retired from his position in 1869 due to widespread internal disagreement over the matter. When the Canadian government approached the Grand Trunk to build the transcontinental railway around the same time, they were turned down.

Establishing a Branchline Empire

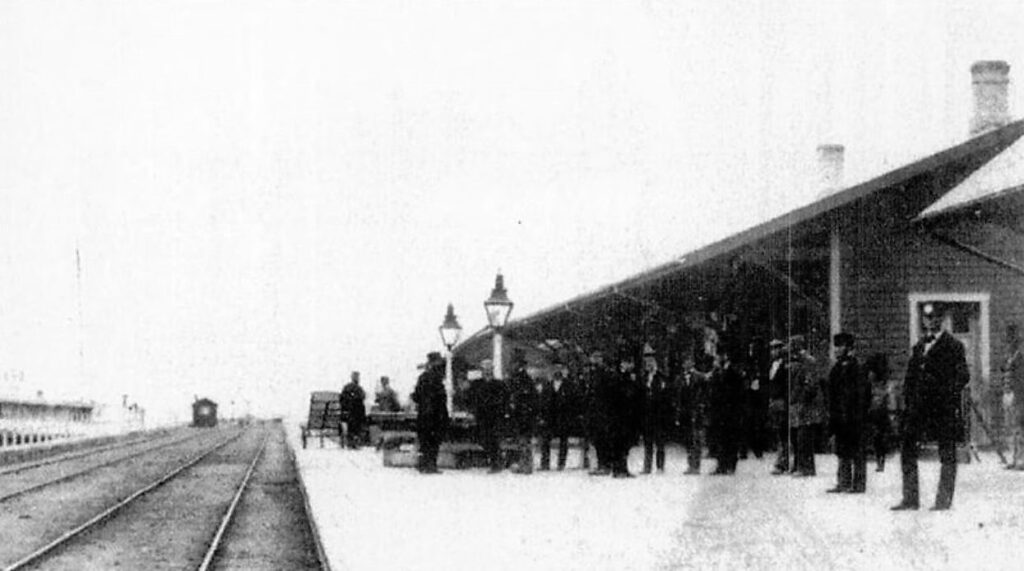

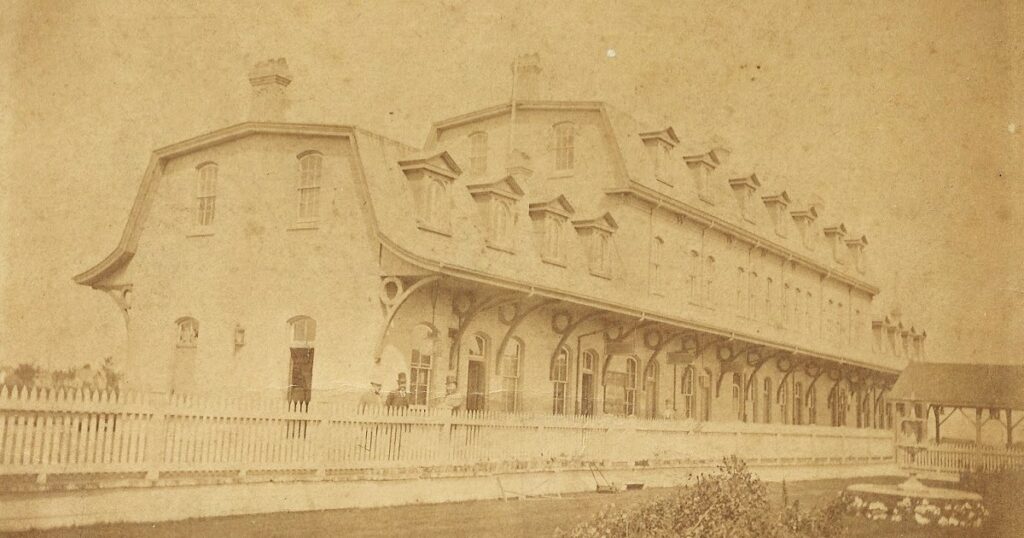

Contrary to Walter Shanly’s earlier quote, Toronto’s first Union Station quickly fell victim to overcrowding. The Ontario, Simcoe & Huron, now rebranded as the Northern Railway of Canada, was the first to vacate it and establish their own passenger terminal elsewhere in 1860. The Great Western Railway would follow suit seven years later. On May 15th, 1866, the City of Toronto agreed to sell a plot of land between Simcoe Street and York Street to the Grand Trunk Railway for $20,000 for the construction of a new Union Station. The original station was torn down in 1871 and a temporary station erected while construction took place. Taking advantage of improved financial conditions, the new station was a far more impressive structure designed by Thomas Seaton Scott and featuring influences from the Italianate and Second Empire styles. It included several design features from the 1855 proposal such as a roof or “train shed” with arched portals where trains entered, except much larger. When the new Union Station officially opened on July 1st, 1873, it was considered the largest and most opulent railway station in Canada. Simultaneously, the provincial gauge had fallen out of favour in Canada due to delays caused by interchanging freight with American railroads. The gauge condition was removed from the loan interest guarantee in 1870, and the Grand Trunk became one of several railways in Canada to make the conversion to 4-foot 8.5-inch standard gauge soon thereafter. The entire Grand Trunk system was converted between 1872 and 1874, which involved the purchase of new locomotives and rolling stock for the new gauge.

The 1870’s saw an increase in new independent railway companies popping up throughout Ontario. The Grand Trunk was neutral or accommodating to some and outright hostile to others. The narrow-gauge Toronto & Nipissing Railway and the Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway for example were permitted to lay a third rail inside the Grand Trunk’s existing tracks in the city. These jointly operated sections would exist as far as Scarborough for the former and Weston for the latter, and included the northernmost track of Union Station which both companies shared with the Grand Trunk. When the Grand Trunk Railway sought to replace its locomotive shed at Queens Wharf with another new roundhouse at Spadina Avenue, the Toronto, Grey & Bruce leased the Queens Wharf facilities in 1871 for a period of ten years. The second roundhouse at Spadina opened during the same year.

Beyond the recent narrow-gauge lines, the well established Great Western Railway, Northern Railway of Canada, and the Midland Railway of Canada had all greatly expanded in southern Ontario. Some of these were directly beneficial to the Grand Trunk for the interchange traffic they offered, while others presented as competitors in the areas they served. In order to gain the edge in the region ahead of the transcontinental railway’s eventual arrival, the Grand Trunk’s General Manager Joseph Hickson and President Henry Tyler began attempting to influence these surrounding railway companies in a way that would play out in their favour. These efforts intensified in the face of a new transcontinental railway with the funding to rival that which the Grand Trunk received from Europe. The Canadian Pacific Railway was incorporated in 1881, and quickly began inserting itself into the Grand Trunk’s territory. After its proxy the Ontario & Quebec Railway was granted a charter, the Grand Trunk’s Joseph Hickson immediately retaliated by announcing his company would solve its poor service between Toronto and Montreal by laying a second track along the entire central division. It wasn’t enough to stop what was coming. There was already talk occurring between the Great Western Railway and Canadian Pacific which prompted the Grand Trunk to hasten its actions. Through influencing its shareholders, the Great Western was amalgamated with the Grand Trunk on August 12th, 1882, adding a vast network of lines throughout southwestern Ontario to the Grand Trunk system. However, the financial cost of this acquisition caused the Grand Trunk to become briefly overextended, and it was unable to do the same with the Toronto, Grey & Bruce before Canadian Pacific leased it in 1883. The Toronto & Nipissing and several other branch lines like it nearby had consolidated under the Midland Railway banner the year prior, and the Grand Trunk quickly set its sights there. They gained control of the entirety of the Midland Railway’s available stock in mid-1883 and began leasing the company on January 1st, 1884. However, the two would not become officially amalgamated until 1893.

One final merger would round off the 1880’s, shortly after the Northern Railway had completed its connection to the transcontinental railway in North Bay in 1886. It had entered a combined management agreement with the Hamilton & North-Western Railway in 1879, forming the Northern and North Western Railway. Joseph Hickson had been buying preferred stock in the Northern Railway and the Hamilton & North-Western for several years at this point. An editorial from the May 1st, 1883 issue of the Hamilton Spectator quoted a municipal council member accusing the Northern & North Western’s General Manager Samuel Barker of being controlled by Hickson and the Grand Trunk. Members of the board who were favourable to Canadian Pacific were gradually pushed out of the company, and the Grand Trunk would gain control of the Northern Railway and its leased entities on January 24th, 1888.

Competition in Toronto and Abroad

By the 1890’s, the Grand Trunk’s board of directors saw the company underperforming against its competitors and in response would seek a new General Manager to introduce more aggressive business tactics. Charles Melville Hays would be chosen in 1896 on the advice of American financier J. Pierpont Morgan. Originally from Illinois, Hays had previous experience in executive positions with the Missouri Pacific Railroad and the Wabash Railroad. It was the opinion of the board that Hays’ “American” approach would be key in making the Grand Trunk more competitive. He would invest in ways which largely resulted in profits for the company, including but not limited to the railway infrastructure itself such as bridges and buildings. Hays’ approach also had a negative impact on the rights of Grand Trunk employees, which was perhaps most pronounced in his actions during the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen strike of 1910.

By this point, the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific had the greatest presence in southern Ontario over other railway companies, and the fierce competition between the two would manifest numerous times in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Canadian Pacific and New York Central, which had also offered some competition to the Grand Trunk in Michigan, gained controlling interests in the Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo Railway in 1895. Soon after, the TH&B planned to run parallel to the Grand Trunk from Hamilton to Toronto. Quick to maintain some control over that area, the Grand Trunk granted running rights to Canadian Pacific over that section of track on May 13th, 1896. This agreement came with numerous conditions which were lightened up in subsequent years. Through passenger service over the joint section began on May 30th, 1897.

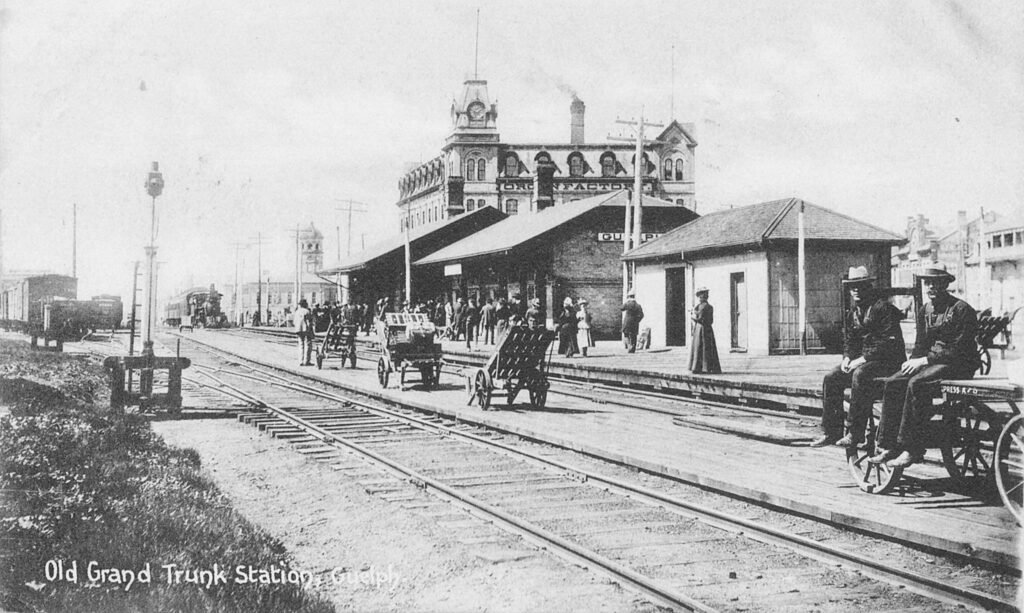

At about the same time, the 1873 Union Station and the adjacent rail corridor saw improvements to reduce overcrowding and streamline operations. Construction on these improvements began in 1893 and included a 7-storey Romanesque office building and entrance on Front Street, a rebuild of the existing train shed, and the addition of a new one along the south side of the station with three tracks. Several interlocking towers were built along the rail corridor on each side of the station to remotely control its switches and signals. The Toronto Terminals Railway would be incorporated in 1906 to manage operations of the Union Station corridor, and the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific would each own 50% of its shares. That year a new threat in the form of the Canadian Northern Railway would arrive from the north, seeking to directly compete with both the Canadian Pacific and Grand trunk.

The Grand Trunk was no stranger to playing dirty when it came to dealing with competitors. One of their earlier instances of doing so in Toronto was when they had physically blocked construction of an additional track of the Credit Valley Railway in 1880, using a locomotive and boxcars along with other debris. With the threat of losing more of its market share to the Canadian Northern Railway, similar tactics were employed. The incident began on the morning of February 6th, 1906, with a Grand Trunk boxcar intentionally placed on a spur. Attempts at clearing the way were obstructed by more rail cars and engines, and even the Grand Trunk employees themselves. The incident ended that afternoon with large quantities of nitroglycerine causing a huge explosion, luckily resulting in no injuries. The conflict was remedied at the insistence of the city through a compromise to allow the Canadian Northern to share the Grand Trunk right-of-way along the Don River to enter Toronto.

The freight yards of the Grand Trunk scattered around Toronto as a result of its mergers would make increased freight traffic difficult and overly complicated to handle. In an effort to consolidate these operations, the Grand Trunk would first construct a freight terminal in the northwest corner of Simcoe and Front Street in 1904. These efforts would continue two years later with the completion of a 200-acre marshalling yard in Mimico, located approximately 10 kilometres west of Toronto. By 1913, a new 34-stall roundhouse and other facilities would be constructed in the southwest corner of Mimico Yard to service freight locomotives between trips.

The Grand Trunk would also make numerous improvements to their broader infrastructure around the turn of the 20th century. Work began in 1889 on double-tracking numerous sections of mainline to allow for a higher volume of rail traffic, with the first section completed between Toronto and Scarborough Junction later that year. The process resulted in the line being rerouted in a number of places to allow for fewer curves and reduced grades. Many new bridges were built along the line to higher standards than their predecessors, several of which are still in place today due to their ability to handle the weight of modern trains. The increased capacity brought on by these double-tracking efforts would set the stage for the introduction of the Grand Trunk’s new flagship passenger train, the International Limited, which made its inaugural run on June 24th, 1900. This train would run between Montreal’s Bonaventure Station and Chicago’s Dearborn Station over the new sections of double-tracked mainline, something that was mentioned often in this train’s advertisements. The International Limited was able to make the trip between Toronto and Montreal in just 7 hours and 25 minutes, giving it the title of the fastest train on the continent at the time. This isn’t too far off the 5 hour ride offered by VIA Rail over the same distance today. The entire trip from Montreal to Chicago took 22 hours and 52 minutes, including a lengthy ferry ride across the Detroit River until the train was later rerouted through the St. Clair Tunnel. In 1902, a Grand Trunk passenger train was used as the test bed for a wireless communication system between a moving train and a station, conducted by McGill University Professor Ernest Rutherford. Wide use of this system would unfortunately not occur, and further tests on similar technology by Canadian National in 1929 would be hampered by the Great Depression.

The Decline and Legacy of the Grand Trunk

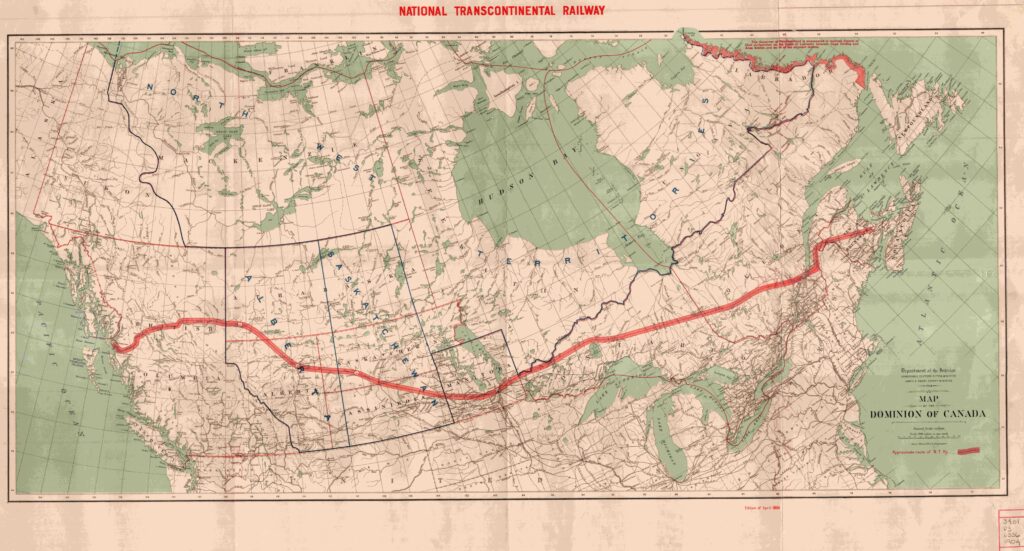

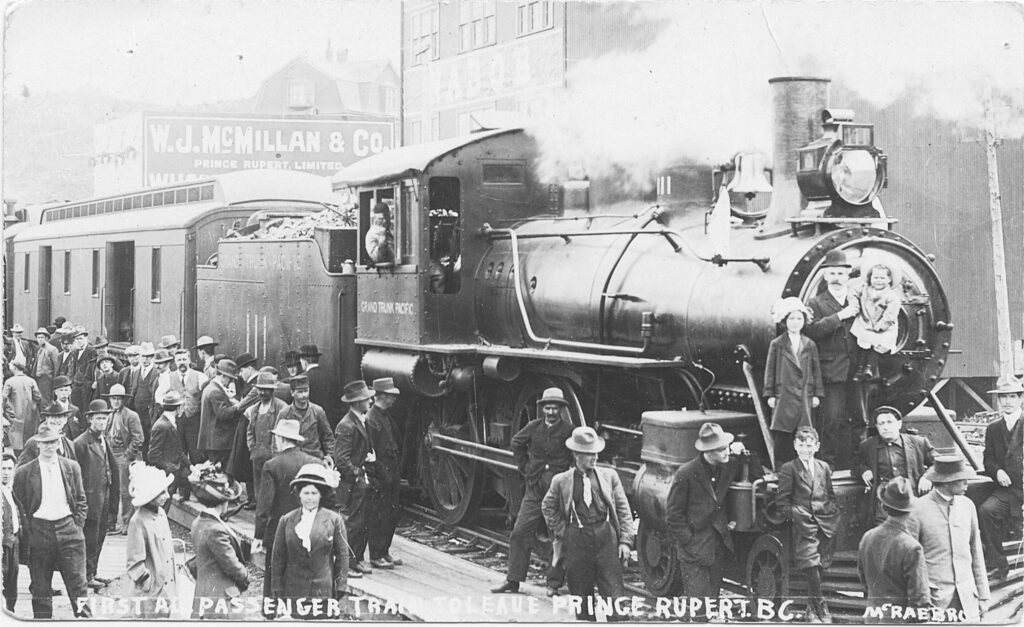

There were multiple factors that contributed to the Grand Trunk’s decline and eventual bankruptcy, not the least of which was the ill-fated pacific extension under the Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad subsidiary. The Grand Trunk had declined offers from the Canadian government to build Canada’s first transcontinental railway on two separate occasions in 1870 and 1880. A few decades later and the Grand Trunk’s two greatest competitors in Canada, Canadian Northern and Canadian Pacific, each had lines to the west while the Grand Trunk did not. The Wilfred Laurier government was also determined to introduce more railway competition to the west to end Canadian Pacific’s rampant price gouging. Initially the government wished to have the Grand Trunk and Canadian Northern cooperate, but it became clear this would not be possible. The GTR would eventually agree to construct the western section, while the eastern section would be built by a government entity called the National Transcontinental Railway and the two would meet in Winnipeg. After both lines were built, the National Transcontinental was to be fully absorbed into the Grand Trunk Pacific. The original plan in 1903 was to reach Port Simpson, British Columbia, much further north than Canadian Pacific’s western terminus of Vancouver and geographically closer to ports in Asia. However, after US President Theodore Roosevelt threatened to occupy the nearby territory in Alaska, Laurier opted to have the Grand Trunk Pacific’s western terminus in a more easily defendable Prince Rupert just to the south of Port Simpson.

Laurier would turn the first sod of the Grand Trunk Pacific in Fort William, Ontario on September 11th, 1905. It would reach Edson, Alberta in 1910 from which it would enter the Rocky Mountains, following Sandford Fleming’s survey through the Yellowhead Pass for the Canadian Pacific a few decades prior which offered easier grades than the Canadian Pacific’s chosen route to the south. The line would be completed to Prince Rupert on April 7th, 1914. Simultaneously, the National Transcontinental Railway was under construction between Winnipeg and Moncton, and it was almost entirely completed by 1913 with its official opening in 1915. Hays wouldn’t live to see the entire system’s completion, as he would die with the sinking of the RMS Titanic on the night of April 14th, 1912 while returning from London where he attempted to solicit more financial support for the Grand Trunk Pacific. While his policies especially regarding the pacific extension are mostly to blame for the Grand Trunk’s fate in the years that followed, Hays’ death is sometimes considered the final straw that signaled the end of the Grand Trunk. It was also later alleged that Hays had deceived the Grand Trunk Pacific’s directors in London by committing them to certain conditions to which they did not agree.

In the years after Hays’ death it became apparent that the Grand Trunk didn’t want to uphold its agreement with the government, first when they cited economic reasons for refusing to operate the National Transcontinental Railway. An article from the Canadian Engineer dated May 10th, 1917 covered the poor financial condition of the Grand Trunk in detail. It notes that as of that date, government subsidies and financial aid to the Grand Trunk were over $28.1 million, while subsidies to the Grand Trunk Pacific had reached over $114.4 million. The article describes the Grand Trunk Pacific as a “fatal mistake”, and quotes a majority report that found the Grand Trunk itself “has not been and is not being adequately maintained”. Then, in 1919, the Grand Trunk defaulted on its loan payments to the government as a result of the enormous costs of building its pacific extension. On March 7th of that year the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was nationalized, and a federal government Board of Management was formed to control it for the time being. The Canadian National Railways had recently been formed as a crown corporation by the federal government to consolidate several other government owned railways, and on July 20th, 1920, the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was merged into it. Eight days earlier on July 12th, much to the dismay of its shareholders, the Grand Trunk Railway was nationalized as well. Legal battles ensued to keep the Grand Trunk independent, but finally on January 20th, 1923, the Grand Trunk was fully absorbed into the CNR.

Even though the Grand Trunk Railway as an organization is long gone, its legacy and the impact it left on Toronto and the rest of Canada is apparent. At the end of its lifetime the Grand Trunk and its subsidiaries totaled 12,800 kilometers in length in Canada, and 1,873 kilometers in the United States. Much of its system survives today as active rail corridors, including a significant portion of the original mainline from Montreal to Toronto. Many structures built by the Grand Trunk have stood the test of time, mostly stations which have been preserved and are in varying states of restoration. Even its former office buildings in Montreal, Quebec and London, England still exist today. One of the last significant construction projects of the Grand Trunk in cooperation with Canadian Pacific was the construction of Toronto’s current Union Station, and its name has been immortalized in an engraving above the columns along Front Street.

Written by Adam Peltenburg

References

Jeanes, D. L. (2006). The Grand Trunk Standard Stations of 1856 and their architect, Francis Thompson. Canadian Rail, (514), p. 239.

Boles, Derek. 2009. Toronto’s Railway Heritage. N.p.: Arcadia Publishing.

Clarke, Rod. 2007. Narrow Gauge Through the Bush: Ontario’s Toronto Grey & Bruce and Toronto & Nipissing Railways. N.p.: R. Clarke and R. Beaumont.

MacKay, D. (1986). The Asian dream : the Pacific Rim and Canada’s national railway. Douglas & McIntyre.

Guillet, Edwin C. 1963. Pioneer Travel in Upper Canada. N.p.: University of Toronto Press. https://books.google.ca/books?id=_Ps2DwAAQBAJ&dq=grand+trunk+railway+%22august+25+1856%22&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

de Fort-Menares, A. M. (1996). Durability and Parsimony: Railway Station Architecture in Ontario, 1853-1914. Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, 21(1), 25-31. https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/71207/vol21_1_25_31.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Esquesing Historical Society. (2017, March 05). Guelph – Toronto Road / Railroad. Retrieved September 29, 2021, from http://esquesinghistoricalsociety.com/2017/03/05/guelph-toronto-road-railroad/

Guillet, Edwin C. 1963. Pioneer Travel in Upper Canada. N.p.: University of Toronto Press. https://books.google.ca/books?id=_Ps2DwAAQBAJ&dq=grand+trunk+railway+%22august+25+1856%22&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

Draft of the second report of the committee on railroads, canals and telegraph lines. 1854. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.64387/7.

The Evening Record. 1854. “Provincial News.” January 25, 1854.

Saint John Observer. 1854. “Various Extracts.” May 23, 1854. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00354_18540523/2.

Maclear & Co. (1856). Agreement between the city of Toronto and the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada for the construction of the company’s tract along the front of the city. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.50170/8?r=0&s=1

Agreement for Amalgamation. 1856. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.18820/6.

London Herald. 1857. “The Grand Trunk Railway.” January 20, 1857. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00709_18570120/2.

Grand Trunk Railway. 1858. Proceedings of Fifth Annual General Meeting, Proceedings of the Fifth Annual General Meeting of the Shareholders of the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada. Montreal, Quebec: John Lovell, Canada Directory Office. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_00396_4/1.

Blackwell, Thomas, and John Robinson. 1860. Report of Mr. Thomas E. Blackwell, Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.22872/50.

Guelph Evening Mercury. 1872. “The Progress of the Grand Trunk.” March 18, 1872. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00211_18720318/1.

Grand Trunk Railway System, 1896 – 1907. (1908). p. 31. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.79274/15?r=0&s=3

The Hamilton Evening Times. 1900. “New Grand Trunk Flyer.” June 25, 1900. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00138_190001/1139.

Meaford Novelty Co. (1913). The Loss of the Titanic. Canadiana.ca, 65. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.77299/10?r=0&s=3

“Position of the Grand Trunk Railway.” 1917. The Canadian Engineer 32 (May). https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_04084_657/6.